This is the second of 6 guest posts on infectious causes of chronic disease.

By Courtney Cook

Scientists have been aware of a relationship between infections and mental illnesses for quite some time. For example, during the 1918 influenza pandemic, some patients were seen to exhibit a delirium unlike that which had typically been associated with a viral infection. In a 1926 report, Karl Menninger called it a "schizophrenic syndrome" and further observed that two-thirds of those diagnosed with schizophrenia after having influenza fully recovered from the mental illness within five years. Such a quick recovery - or even recovering at all - is unusual for such mental disorders, which might suggest a curable agent caused the disease in the first place.

Scientists have been aware of a relationship between infections and mental illnesses for quite some time. For example, during the 1918 influenza pandemic, some patients were seen to exhibit a delirium unlike that which had typically been associated with a viral infection. In a 1926 report, Karl Menninger called it a "schizophrenic syndrome" and further observed that two-thirds of those diagnosed with schizophrenia after having influenza fully recovered from the mental illness within five years. Such a quick recovery - or even recovering at all - is unusual for such mental disorders, which might suggest a curable agent caused the disease in the first place.

Schizophrenia is one of several chronic diseases of the central nervous system. Affecting the brains of about 1% of the adult population in the United States and Europe, those affected typically hear voices, see things that aren't there, and have other unusual thoughts and perceptions. Patients can also have difficulty with movement, speaking, expressing emotions, and memory. Schizophrenia was commonly thought to have origin in genetic predisposition for the disease, with environmental factors also playing a role.

(More after the jump...)

Epidemiological studies of schizophrenia have shown winter births, urban births, and perinatal/postnatal infections to all be risk factors for development of schizophrenia later in life. It makes sense for the next step in the process to be to at least consider an infectious cause. Winter months have high incidence of a variety of infections, and urban areas often have high rates of disease due to overcrowded living areas and other such factors.

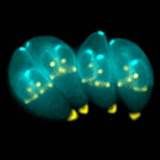

While several bacteria and viruses have been studied as possible causes for schizophrenia, Toxoplasma gondii has emerged as a frontrunner in recent years. T. gondii calls cats and other felines its definitive hosts, but can also infect intermediate hosts, including humans. While cats appear unaffected as carriers, T. gondii has been seen to play a role in causing abortions and stillbirths in mammals, as well as being selective for infections of muscle and particularly brain tissue, where it can affect levels of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and norepinephrine, similar to what occurs in patients with schizophrenia. It also primarily affects glial cells, particularly astrocytes, and studies of the brains of deceased schizophrenic patients have shown glial abnormalities and decreased numbers of astrocytes.

T. gondii can also cross through the placenta, infecting the fetus. Symptoms of congenital toxoplasmosis, which can include hydrocephalus and cognitive impairments, have been observed in adults later on in life who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia or other types of psychosis.

While all of these associations seem to arrive at a conclusion that T. gondii could be an infectious cause of schizophrenia, we should be careful not to jump to that conclusion so soon. While studies in this area have shown significant associations between the two, sample sizes in these studies have been small. Given the low prevalence of schizophrenia, however, it might be difficult to reach adequate numbers in a study. It could be more effective to include other psychoses, in addition to schizophrenia, in these studies.

Last month's issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry published a study looking at children in Sweden that had been diagnosed with a CNS infection before turning 12 and followed them to see what, if any, psychotic illnesses developed later in life. The authors conclude that viral CNS infections were associated with development of schizophrenia and other disorders, particularly mumps virus and cytomegalovirus. Toxoplasma gondii is not even mentioned as an infectious agent affecting the cases. This presents a whole different possibility for a cause of the disease.

With such a wide variety of theories surrounding the infectious causes of schizophrenia, there does not appear to be a specific answer in sight. Narrowing it down to one particular bacterium or virus would open the door for the development of a possible vaccine to prevent the mental illness. But with so many different answers to the same question, it becomes difficult to know which answer is the "right" one.

Courtney Cook is a first year M.S. student in epidemiology, and currently holds a B.A. in mathematics. Her research interests involve infectious disease epidemiology, particularly in children. She hopes to apply these interests toward her ultimate career goal of practicing medicine, specializing in pediatrics. It also happens to be her birthday today.

References

Barry, J.M. The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. 2005.

Dalman, C., et al. (2008) Infections in the CNS During Childhood and the Risk of Subsequent Psychotic Illness: A Cohort Study of More than One Million Swedish Subjects. Am J Psychiatry 165 (1): 59-65. Link.

Torrey, E.F., Yolken, R.H. (2003). Toxoplasma gondii and Schizophrenia. Emerging Infectious Diseases 9 (11): 1375-1380. Link.

Image from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Toxoplasma_gondii.jpg

- Log in to post comments

How many times do I have to say it? The micro-organisms in my brain don't cause disease! They're friendly fellows who like my company. No, it's the evil medi-chemi-pharmaindustrial complex that causes imbalance in the vital fluids, leading to psychic disturbances. Them and the alien rays. /snark

Fascinating. I had no idea there had been so much work on connecting infectious disease with schizophrenia. The implications are amazing, as is the realization that we have so very far to go in this field.

A good summary.

I wonder if anyone has ever done antibody testing of schizophrenia patients to see if there may be some common history of infection. This would be particularly interesting for those viruses which remain in the body for life, sometimes supposedly completely asymptomatic, such as Epstein-Barr, herpes viruses, etc. These would not be likely to show up much in histories of CNS infections.

Happy birthday!

So the possible link is exclusively with congenital toxoplasmosis? I would have thought rates of noncongenital toxoplasmosis were too high for any correlation with a low-incidence condition to be meaningful...

Thanks for this balanced post, Ms. Cook. Like you, I think we need more information on the postulated link.

Last year, the Schizophrenia Bulletin devoted an issue to this topic. Schwarcz and Hunter http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/33/3/6…

give an overview of previous work on mechanistic hypotheses including kynurenic acid and its effects on NMDA receptors and others. The possible mechanisms are in place.

What I have trouble with (perhaps because I don't know much about it) is this:

Inflammatory responses in the brain, including the response to T. gondii (especially in the immunocompromised host), drive reactive astrogliosis: more astrocytes that are larger and more active. But as you note, schizophrenia patients reportedly have lower numbers of astrocytes.

Is this merely a function of when, that is, at what time during disease researchers have looked at human samples? Or is it truly a contradiction?

Rats infected with T. gondii do not fear cat urine the way

uninfected rats do.

This makes them more likely to get eaten by cats...

I do not fear cat urine either. Please help me.

This post was really cool, it'll help with my current Psychology topic: abnormality and disorder (my favourite, it has to be said). Shall take that to class tomorrow.

Swot!

Yes, I know ;)

~Chris

The Book Swede

Well it certainly clear that schizophrenia can be induced by physical conditions, a traumatic head injury can actually case paranoid schizophrenia (http://paranoidschizophreniasymptoms.net/causes/head-injury/)

Matt