This week I want to build on something I discussed near the end of last week's problem. I mentioned that a problem's genre should in some way complement its theme. So, if your problem is a selfmate, it is better if the theme employs logic that is specific to the selfmate genre. If your idea could as easily be expressed in a direct mate, then perhaps you have not chosen the most appropriate way of expressing your idea.

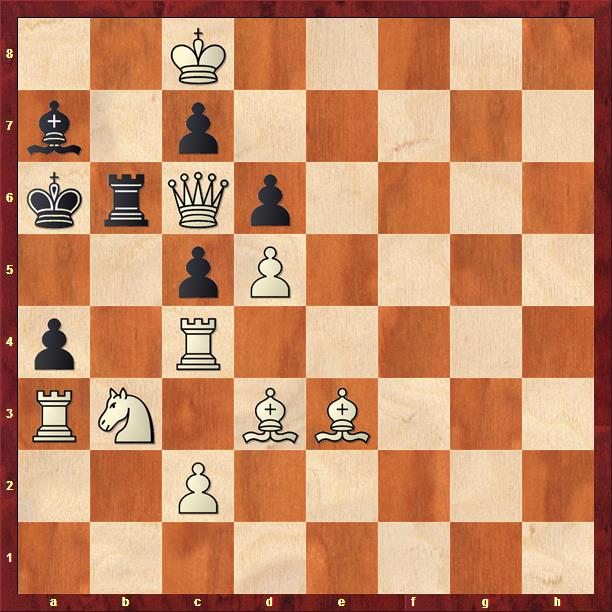

I'd like to illustrate this with two of my own problems. We'll go through the first one quickly. It is a selfmate in three:

This problem was published in the July 1991 issue of the British Chess Magazine.

The basic idea seems clear enough. White will try to stalemate black in the northeast corner, at which point black's only move will be to promote his b-pawn. This will discover checkmate from the black bishop in the corner.

The key is the waiting move 1. e8N!, leading to two variations. We have: 1. ... Bxg8 2. Rxg6+ Kh7 3. Rg5 b1 any, mate. Or: 1. ... Rxf6 2. Rh5+ Kg6 3. Rxh7 b1 any, mate

Black is forced to incarcerate his own pieces. Pretty! But the problem has several drawbacks. For example, the only role of the key move is to place an extra guard on g7. The first of the two lines works even in the diagram position. The setting is also rather cluttered. But the most serious issue is that this is not really a selfmate at all. All of the strategy is about figuring out how to stalemate black on the kingside. The selfmate mechanism with the black bishop in the corner is just an add on that does not enhance the strategic interest of the problem.

Now, this was composed very early in my career as a problemist, such as it is. I was not even aware that “direct stalemate” was an actual genre. Once I did become aware of that fact, by seeing such a problem published in a different problem magazine, I went back to the drawing board and found a different, and much better, way of expressing my idea.

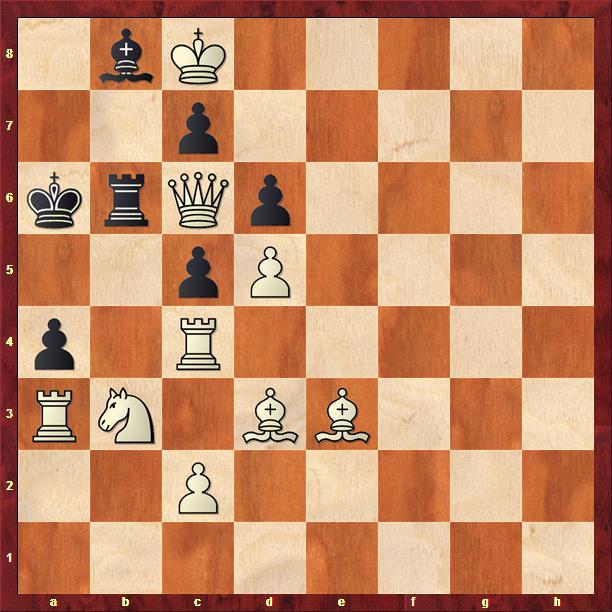

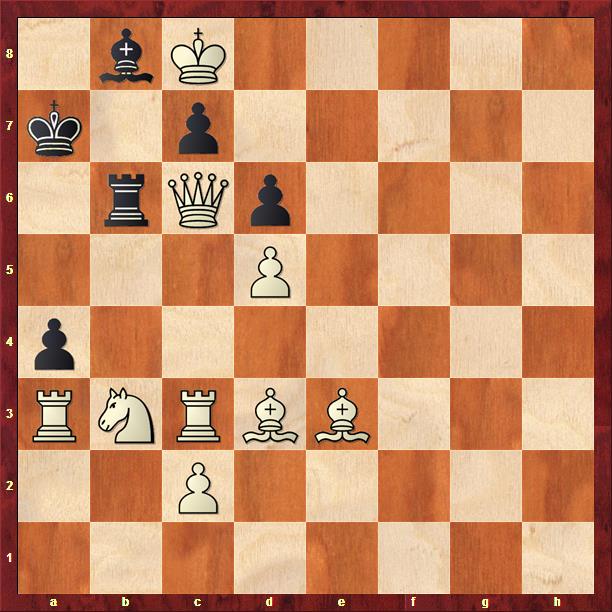

So, the second problem calls for stalemate in three:

This was published in the July-October 1992 issue of the U. S. Problem Bulletin. Just to be clear, white's goal is to inflict stalemate on black in no more than three moves. Checkmate has no appeal for white, which is a pity, since that is easy to achieve in the diagram position.

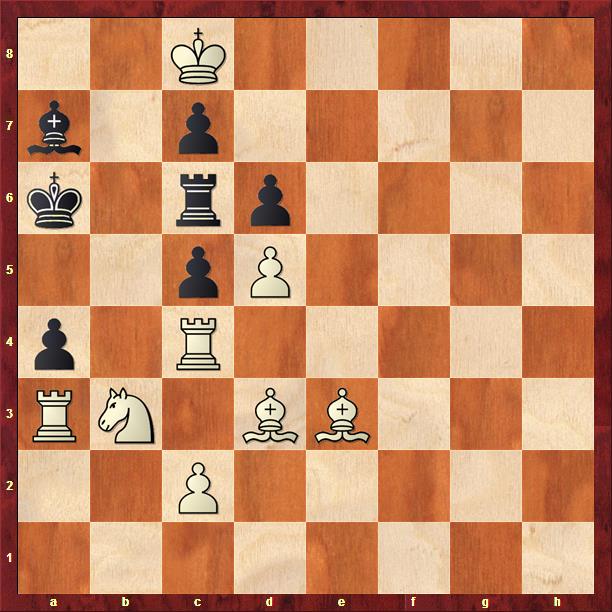

Black currently has a mobile bishop on a7, and a mobile rook on b6. If the white rook on c4 moves out of the way, then the black pawn on c5 becomes mobile. So, all of the action revolves around the a7-g1 diagonal. The key move is 1. Be3!

This is another waiting move. Black now has two moves. After 1. ... Rxc6:

white continues with 2. Rxa4+ Kb6 3. Rxa7 stalemate:

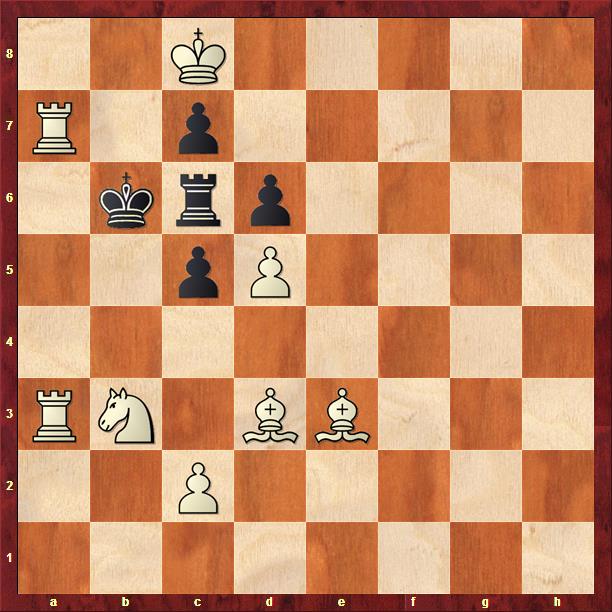

And after 1. ... Bb8:

We get 2. Rxc5+ Ka7 3. Rc3 stalemate

Compared to the first problem, this is a considerable improvement. The key involves a move to the thematic line, and it sets up both of the ensuing variations. Moreover, in each line we find that among the three mobile black units, one is incarcerated, one is pinned, and one is captured. This adds considerable thematic unity to the variations. And, best of all, this is clearly a stalemate specific idea. No silly selfmate mechanism just tacked on at the end.

Not a masterpiece, certainly, but a solid, enjoyable problem, and one I still look at with some pride. See you next week!

- Log in to post comments

Interesting. I am not sure I have seen a stalemate problem before.

I'm looking forward to some evolution discussions. Did anyone see Myers valiant combat with strawmen over Metaspriggina, a vertebrate found in the lower Cambrian? Great stuff...

http://freethoughtblogs.com/pharyngula/2014/09/04/a-fish-a-rabbit-same-…

...and a well-deserved spanking:

http://www.evolutionnews.org/2014/09/metaspriggina_r089761.html

A very clear exposition of your theme. Nice key move on the 2nd problem!

Jason,

Just a minor quibble. In the first line on the second problem, I was temporarily confused. Your notation has white's second move as 2. Rxa4+. You really should have written this as 2. Rcxa4+ since the rook on the a file could take the a4 pawn and give check. Clearly that move doesn't lead to stalemate since black would be able to capture that rook on a7.

Like I said, I minor thing, but I was a bit confused on first reading. Probably that's on me, but adding the "c" to the notation would help.