Folks, I'm back from Atlanta. This trip was the meat in a travel sandwich that started with my brief visit to Indiana two weeks ago, and ends with my trip to New York on Wednesday. (I'm speaking at The Museum of Mathematics!) Busy, busy, busy. But not too bus to serve up a Sunday Chess Problem.

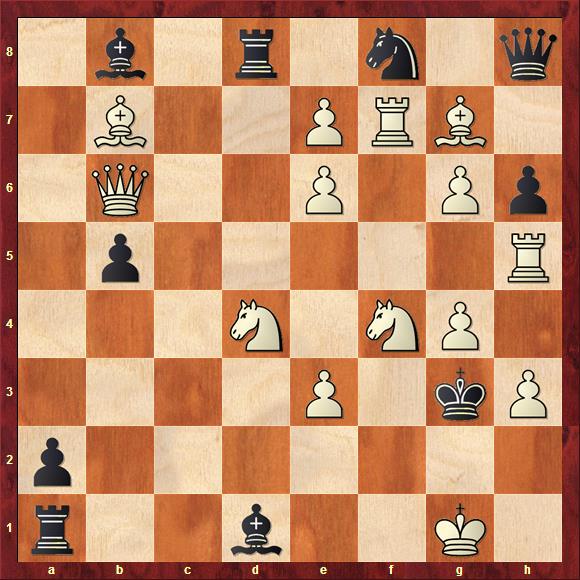

This week we have another selfmate for you from Milan Vukcevich. This was composed in 1990 and calls for selfmate in three:

Recall that in a selfmate white plays first and tries to force black to give mate in no more than the stipulated number of moves. Black, for his part, does everything in his power to avoid giving mate. It's a complete inversion of normal chess logic!

So let's have a look. At first blush it seems like white's task is easy. Plainly he will try to coax the black bishop off the first rank, thereby discovering check and mate from the black rook on a1. He even seems to have an easy way of doing this, since he can move either of his knights to e2. In so doing he gives check to the black king. The only way out of this check is for black to capture the knight with his bishop.

But there is a problem. If we try 1. Nde2+, we find that we are opening a line for the white bishop on g7. When black captures the knight it will not be mate, because the white bishop can capture the black rook.

And if we try 1. Nfe2+ instead? This time we have opened a line for the white rook. When black captures the knight white will be able to interpose this rook on f1, thereby disrupting the mate. No good!

What to do? A possible solution presents itself. White can try self-interference! How about 1. Rf6 as a way to start? This interferes with the white bishop, meaning that 2. Nde2+ is now a real threat. Sadly, though, black can simply remove the threatening knight with 1. ... Rxd4.

And if white tries the other self-interference with 1. Bf6? True, since the rook on f7 is now cut off, we really are threatening 2. Nfe2+. But now black can just remove this knight with 1. ... Bxf4, and white has no continuation. Drat!

Don't give up! For now maybe we see the solution. We should not give up so easily on white's self-interference idea. We simply need to prepare it by forcing black to disrupt one of those knight-capturing defenses. That can be done with 1. Qd6!

We now have a new threat. If black does nothing, white will continue with 2. Nd5+ Rxd6 (or Bxd6) 3. Rf3+

Now black is forced to play 3. ... Bxf3 mate. The ball is in your court, black!

Black does have the unimportant defenses 1. ... Nxe6 and 1. ... Nxg6. White deals with these with the prosaic 2. Nfxe6/Nxg6+ followed by Rf3+. Mission accomplished.

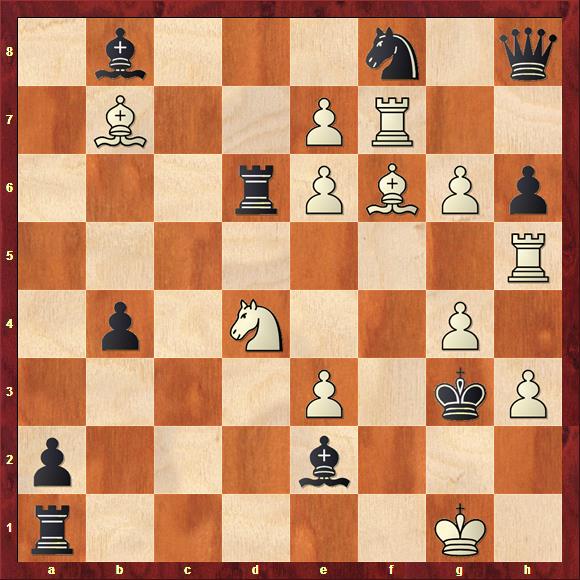

So black must take the queen. But if he tries 1. ... Rxd6 then his own bishop is obstructed, leaving him without the Bxf4 defense. White now plays 2. Bf6 and black has no defense to 3. Nfe2+ Bxe2 mate (In the diagram I have had black play 2. ... b4 as a pointless waiting move).

And if black takes with the bishop instead, then his rook his interfered with, eliminating the Rxd4 defense. Play continues 1. ... Bxd6 2. Rf6 b4 3. Nde2+ Bxe2 mate.

Very nice! In problem jargon, we have here two familiar interference themes. In the tries we see a white rook and a white bishop alternately interfering with each other on the same square (f6). This is known as a Grimshaw. In the play we see the white queen simultaneously interfering on two black lines. This is known as a Nowotny interference. When black captures the interfering white piece, the other black piece remains obstructed.

Incidentally, I recently checked the visitation stats for my recent posts, and it turns out these chess problem posts are attracting a lot of page views. Cool! These posts don't attract a lot of comments, but I'm glad folks are stopping by for a look.

See you next week!

- Log in to post comments

Un. Be. Liev. A. Ble.

I wonder. How long would it take a reasonably experienced problem composer to put together something this loaded?

Milan Vukcevich was one of the best composers in history, prior to his death in 2003. He seemed to be a bottomless pit of good composing ideas. I recently acquired a book of his best compositions, which is why I have been featuring some of his problems lately.

Problems featuring long-distance interferences like this can be difficult to compose. It's incredible that white has time for non-checking continuations on his second moves.