tags: Solomon Islands Frogmouth, Rigidipenna inexpectatus, Podargus ocellatus inexpectatus, birds, birding, ornithology

Gone are the days when animals were classified to taxon based solely on bone structure (osteology), body structure (morphometrics) or behavior (ethology), or some combination of these characters. Currently, scientists have a suite of powerful tools for classifying creatures to taxon, and analyses using a combination of these methods is allowing us to come to a deeper understanding of all animal life. As a result of using these techniques, a new species of bird has been reported, and it was under our very noses all along.

In a recently published paper, a group of scientists led by Nigel Cleere re-examined the taxonomic classification of a particular subspecies of frogmouth, Podargus ocellatus inexpectatus. As a result of this work, Cleere was in for a surprise: his bird was so unique that it was reclassifed into a new species and genus -- a scientific event that happens perhaps once every few years.

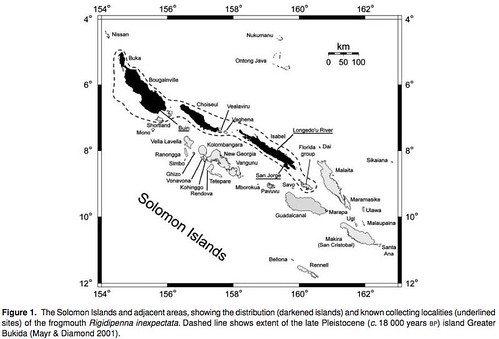

This medium-sized bird is endemic to the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific Ocean, located east of New Guinea. In addition to this newly named genus, there are two other genera of frogmouths in this same family: one lives in southeast Asia and the other is found on Australia and New Guinea. But the newly described and named Solomon Islands Frogmouth is known to inhabit only three islands: Isabel, Bougainville and Guadalcanal (figure 1);

By analyzing multiple characters, including plumage, morphometrics, osteology, molecular genetics and behavior, the group demonstrated that this avian subspecies differs markedly from another, similar-looking species that was originally thought to be a close relative, Podargus ocellatus. The group christened this new bird the Solomon Islands Frogmouth. Their analysis resulted in the Solomon Islands Frogmouth being elevated to full species status, and even more remarkably, it has also been reclassified from Podargus ocellatus inexpectatus and placed into its own unique genus; Rigidipenna inexpectatus.

"This discovery underscores that birds on remote Pacific islands are still poorly known, scientifically speaking," said David Steadman, one of the study's co-authors. "Without the help of local hunters, we probably would have overlooked the frogmouth."

Frogmouths are predatory birds named for their wide, strong beak that resembles a frog's mouth. Their beak also has a small, sharp hook on the end, similar to an owl, making them unique in the bird world. Using their remarkable beak, Frogmouths eat almost any creature that can fit into their mouths, including insects, rodents, small birds and even frogs.

Currently, within the Frogmouth family, Podargidae, there there are nine species of Batrachostomus and three species of Podargus frogmouths, including Podargus ocellatus, which was thought to be the sister species to this bird that was re-examined. Because of their close evolutionary relationships, the authors compared the Solomon Islands Frogmouth to several close relatives and found that they looked very different and had markedly different plumages. First, it has distinct barring on its primary wing and tail feathers, where other frogmouths are more uniform. Additionally, it has creamy or white speckles on its breast and underbelly that are more pronounced than on other frogmouths (see figures 2 and 3);

Additionally, the Solomon Islands Frogmouth is probably not a very accomplished of a flier because it has eight tail feathers, instead of the typical 10 to 12 for other frogmouths. This reduction in tail feathers would affect its ability to fly and would also reduce its maneuverability.

"These are island adaptations that work to keep the bird on the island," Steadman pointed out.

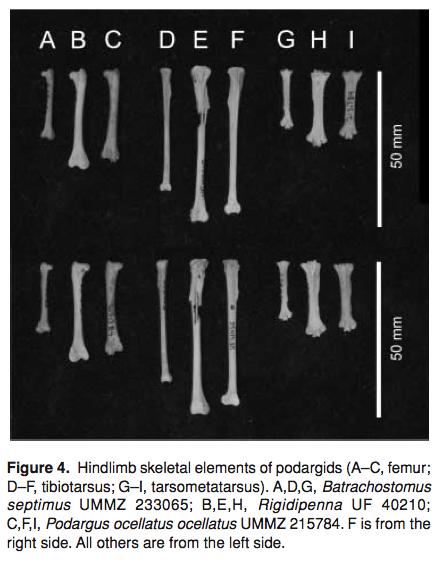

The structure of the same bones from these three species also are obviously different and unique when compared to each other (figure 4). Further, measurements and other detailed osteological analyses yielded more data that revealed these three taxa to be distinct;

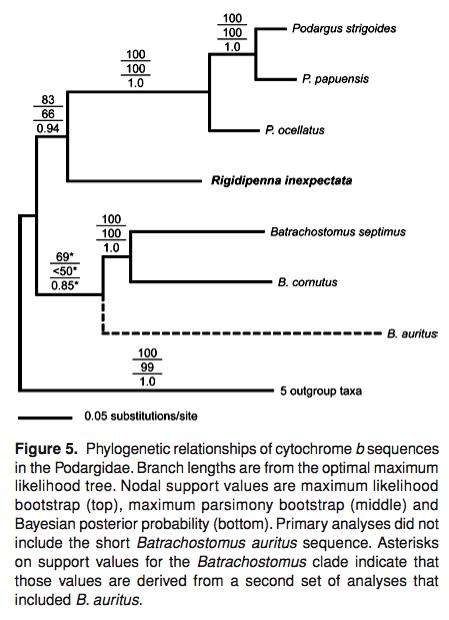

Molecular (DNA) analyses of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene sequence from seven closely related podargids showed that all these species are not only genetically distinct from each other, but they are quite old as well, as demonstrated in this phylogenetic tree (figure 5). Additionally, the genus, Rigidipenna, is basal to Podargus;

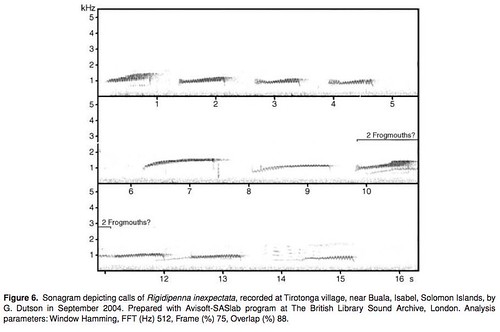

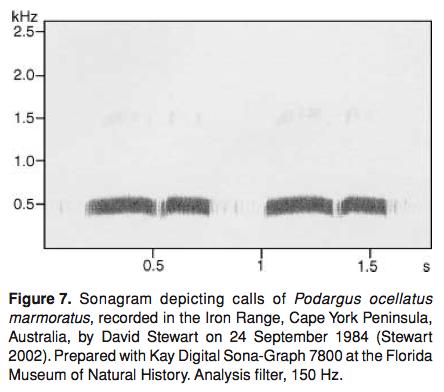

Further, it is likely that, if they are distinct species, Podargus ocellatus and Rigidipenna inexpectatus would have distinct calls. You will recall that these two species were originally thought the be very closely related sister taxa, which would mean their calls should be indistinguishable or at least very similar, but they are not as you will notice in these sonograms (figure 6 as compared to figure 7);

After learning of this study, Van Remsen, curator of birds at the Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science, said that this new frogmouth genus serves as a poignant reminder that birds of the tropics, particularly from the southern Pacific Ocean, have barely been studied by scientists.

"They've barely been studied, much of what we know comes from antiquated or casual observations," Remsen said. "The biology of birds in these regions is, to a great extent, obscured by stale, hand-me-down classifications from an earlier era. A combination of detailed morphological and genetic analyses reveal that this frogmouth -- formerly dismissed as just a race of an existing species -- actually cannot be placed confidently in any existing genus, and so the data demand naming a new one."

Certainly, the geographical origins of the enigmatic frogmouth family have always been unclear, especially considering the uncertainty of their familial relationships. But the discovery that the newly described Rigidipenna inexpectatus is nestled within the Frogmouth family and basal to Podargus suggests that this family of birds began evolving in the southern hemisphere rather than in Europe, as currently thought based on fossil finds.

"That this should prove to be such a distinctive new genus, which it unquestionably is, has profound biogeographical implications and represents a real breakthrough in elucidating the evolutionary history of the family," said Storrs Olson, a senior zoologist with the Smithsonian Institution.

Sources:

Original paper: A new genus of frogmouth (Podargidae) from the Solomon Islands -- results from a taxonomic review of Podargus ocellatus inexpectatus Hartert 1901, by Nigel Cleere, Andrew W. Kratter, David W. Steadman, Michael J. Braun, Christopher J. Huddleston, Christopher E. Filardi & Guy Dutson. Ibis (2007), 149, 271-286.

- Log in to post comments

Having three parts, this name describes a subspecies...

The article gets this right: Rigidipenna inexpectata. This is because Podargus is a he while Rigidipenna is a she -- species names that are adjectives must agree in gender with the genus name, so they change when they are shuffled around between genera.

R. is not at the base of the tree according to fig. 5, instead the basal divergence between the living members of Podargidae is between Batrachostomus on the one hand and (Podargus + Rigidipenna on the other.

As far as I know the fossil podargids from the northern hemisphere are outside of this clade, so two separate questions got conflated here -- where the split between Podargidae and its closest relatives happened (in the northern hemisphere) and where the ancestor of the extant species lived (in the southern one).

Lastly, note that the decision to erect a new genus was arbitrary: the species could have been kept in Podargus without making the latter paraphyletic or anything. I'm not saying it shouldn't have been done or shouldn't be recognized -- I just say the genus is not a discovery, it is a convention. Probably it's meant to draw well-deserved attention to the fact that the newly discovered species is so far away from the other three in terms of branch lengths. (The species is a discovery under most species concepts, because keeping it in P. ocellatus would have made that species paraphyletic and unusually diverse.)

Oops, forgot to close the parenthesis in (Podargus + Rigidipenna).