tags: birds, ornithology, Common Raven, Northern Raven, Corvus corax, animal behavior, animal culture, aggression, dominance hierarchy, social groups, social conflict, post-conflict behavior, consolation, empathy, researchblogging.org,peer-reviewed research, journal club

Common Raven, Corvus corax, showing off at Bryce Canyon National Park, USA.

Image: United States National Park Service (Public Domain) [larger view]

Humans have long tried to distinguish themselves from other animals on the basis of characters that are perceived to be unique, such as tool design and use, planning for the future and the seemingly "human" capacity for empathy. But one by one, these "unique" characters are found to be shared with other animals. For example, early research shows that making and using tools is shared with our closest relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos. Since we have a shared evolutionary ancestry, this is not terribly surprising. But when a distantly related animal, such as the New Caledonian Crow, Corvus moneduloides, demonstrates that they also are very capable tool-makers and users [DOI: 10.1126/science.1073433], evolutionary biologists sat up and took note. As if that wasn't enough, once again, another feature of human "uniqueness" is being called into question because new research has documented what many bird watchers have known for decades; ravens apparently console their friends after an aggressive conflict with a flockmate.

This is interesting because for a bystander -- a flock member, in this case -- to console the victim of an aggressive conflict, the individual must first recognize that the victim is distressed and then must act appropriately to alleviate that distress, a complex behavior that requires sensitivity to the emotional needs of others -- a trait previously attributed only to humans. Of course after deciding that only humans have this special ability, research has since found that our closest relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos also "console" victims of conflict [DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0804141105], but researchers haven't looked closely at many species.

As bird watchers will tell you, many birds are also highly social and very intelligent, two traits that might be prerequisites for empathy. Although very little is known about empathy in birds, there is some tantalizing evidence that it exists. For example, a recent study of Greylag Geese, Anser anser, found that flock members who observed a conflict involving either their partner or a family member experienced an increase in heart rate (a measure of distress) -- consistent with an empathic response [DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0146]. Another study, this time in Rooks, Corvus frugilegus, shows that members of breeding pairs perform affiliation behaviors following conflicts, suggesting that pair-bonded individuals may actually be consoling their partner when s/he is distressed [DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.025].

This evidence is certainly intriguing, but what happens in young birds that have not yet formed a pair bond? Do they form empathetic "friendships"? To answer this question, a team of researchers at the University of Vienna, Orlaith Fraser, a postdoc, and her co-author, Thomas Bugnyar, a teaching fellow, decided to investigate further. They chose to study the Common Raven, Corvus corax. Like the Rook, the Common Raven is another typical member of the corvid family in that they have complex and long-lived social relationships, and their craftiness and intelligence are legendary -- characters that are associated with the capacity to show empathy. Further, ravens are large birds that do not breed until they are between 3-10 years of age, so they are natural choices to study a complex social behavior in birds.

To do this work, Drs. Fraser and Bugnyar removed 13 Common Raven nestlings from four nests (two were zoo bird nests, the other two were wild raven nests) and hand-raised them. After fledging, the young birds were housed together in a large outdoor aviary at the Konrad Lorenz Research Station in Austria in the company of an adult male and female raven who were not related to any of the hand-reared birds. The aviary was made to look as natural as possible, and included trees and other plants, tree trunks and branches, pools of water and stones, and the ravens were given plenty of food and water. (Sadly, the "naturalness" of this enclosure also led to the deaths of two of the young birds who were killed by predators during the course of this study).

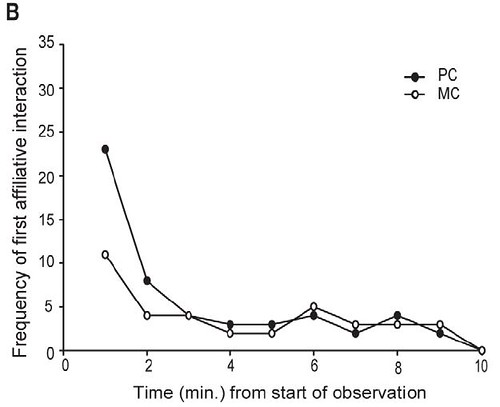

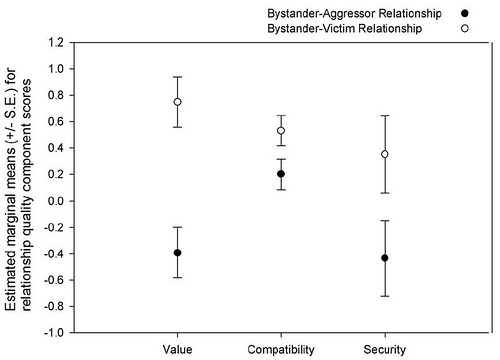

Drs. Fraser and Bugnyar began their study by documenting the frequency of affiliative behaviors in these birds, using a standard protocol developed for primate research. They watched the aftermath of 152 fights between these juvenile ravens during the following 23-month period of time, and recorded the identities of the aggressor, the victim and the bystanders (nearby flock members), along with the intensity of the conflict (a chase flight or hitting were rated as "high intensity", whilst a forced retreat was "low intensity"). All affiliative ("consoling") behaviors -- defined as contact sitting, preening or beak-to-beak or beak-to-body touching between the victim of the conflict and an individual flock member -- were recorded during the ten minutes following each conflict. These post-conflict time periods (PC) were then matched to a control period (MC) for the same victim raven on the next possible day and the frequency and nature of the affiliative interactions that occurred in those time periods were compared (Figure 1):

Figure 1. Demonstration of bystander affiliation and solicited bystander affiliation in ravens. Frequency distributions of latency to first affiliative post-conflict interaction directed from a bystander to the conflict victim (A) and directed from the victim to a bystander (B) in post-conflict periods (PCs; filled circles) and matched control periods (MCs; open circles).

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010605

Surprisingly, these data reveal that flock members were 2.5 times more likely to offer affiliation to the victim of a conflict without the victim first soliciting it. This occurred most often among those members of the flock that were related by kinship (data not shown), but it still occurred at a measurable rate among unrelated birds.

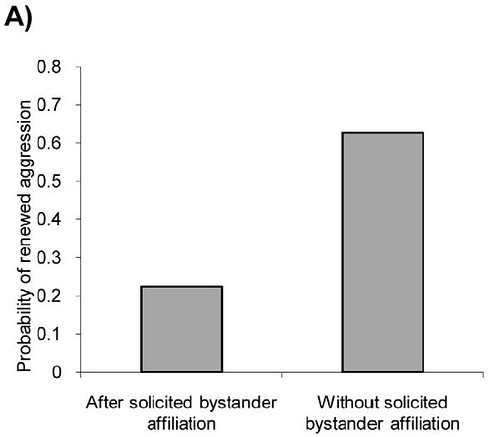

Was unsolicited affiliative behavior somehow protective for the victim? Actually, no: renewed aggression was just as likely in these situations (Figure 2):

Figure 2. The interdependency of solicited bystander affiliation and renewed aggression between former opponents in ravens. *P < 0.005

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010605

There are several interesting things to note here: first, the victims of aggression did not redirect their own aggression towards another individual in their social group. Thus, providing affiliative behaviors to the victim of a conflict didn't carry any exceptional risks to other flock members. Second, since renewed aggression was less likely to occur while affiliation was taking place, the losers tended to actively solicit affiliation from their fellow flock members.

Interestingly, Drs. Fraser and Bugnyar did find that even though the victim was generally at risk for renewed aggression from the same attacker in the immediate post-conflict period, they also found that the victim and aggressor sometimes engaged in affiliation. But this finding was statistically weak, and thus was dismissed as probably being a random event rather than a deliberate strategy to diffuse tension.

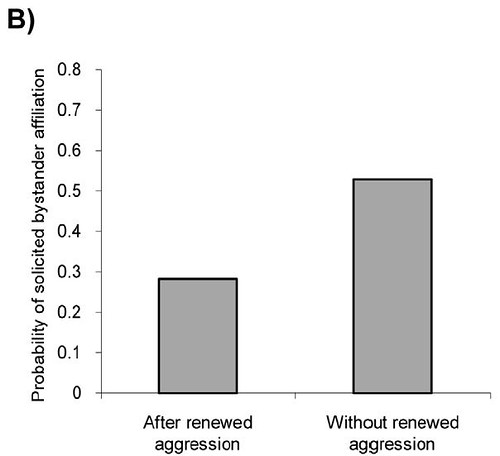

Drs. Fraser and Bugnyar also investigated the genetic relationships between victims and flock members who engaged in affiliative behaviors and found there is a relationship (Figure 3):

Figure 3. The quality of bystander-aggressor and bystander-victim relationships in ravens. Results of LMM analyses comparing components (value, compatibility and security) of the bystander's relationships with the aggressor and the victim when post-conflict affiliation from a bystander to the conflict victim occurs.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010605

Basically, affiliative behaviors occurred most often when the flock member had a closer social bond with the victim raven than with the aggressor. Furthermore, the team observed an increasing probability of unsolicited bystander affiliations after more intense conflicts (when the victim was more likely to be distressed). This trend was not seen for solicited affiliations and conflict intensity [data not shown].

"The findings of this study represent an important step towards understanding how ravens manage their social relationships and balance the costs of group-living," Drs Fraser and Bugnyar write. "Furthermore, they suggest that ravens may be responsive to the emotional needs of others."

What does this research mean when placed into a larger (evolutionary) context? As I mentioned, humans have long tried to find those characters that separate us from other animals, yet these same characters, such as tool use, have been found in close relatives. Of course, sharing some characters with other great apes makes sense since we shared a recent ancestor that probably possessed these same characters.

But once again, as with the tool-making crows of New Caledonia, those fascinating birds have confounded this simplistic world view because they share many "special" traits with humans despite the fact that they are not closely related to mammals at all; instead, birds are modern dinosaurs. Birds represent an evolutionary innovation of one branch of ancient reptiles whilst mammals are an offshoot from a different branch of this same clade. Because the reptiles are not known to make or use tools, to plan for the future or express affiliative behaviors, nor any of those other characters that seem to make humans "unique," this raises important questions regarding the "difficulty" of evolving a seemingly complex social behavior, such as consolation/empathy. Or is "empathy" simply part of what comprises a long-term pair bond in a social animal?

Source:

Fraser, O., & Bugnyar, T. (2010). Do Ravens Show Consolation? Responses to Distressed Others. PLoS ONE, 5 (5) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010605

Also see:

Fraser, O, Stahl, D, & Aureli, F. (2008). Stress reduction through consolation in chimpanzees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0804141105 [PDF]

Seed AM, Clayton NS, & Emery NJ. (2007). Postconflict third-party affiliation in rooks, Corvus frugilegus. Current Biology 17: 152-158. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.025 [PDF]

Wascher, CAF, Scheiber, IBR, & Kotrschal, K. (2008). Heart rate modulation in bystanding geese watching social and non-social events. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275:1653. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0146 [PDF]

Weir, AAS, Chappell, J, & Kacelnik, A. (2002). Shaping of hooks in New Caledonian crows. Science 297: 981. DOI: 10.1126/science.1073433 [PDF]

Intriguing stuff.

In the August 2010 Scientific American, there is a great article regarding new evidence that ancestors of modern birds shared the planet with dinosaurs up to about 3 million years before the end of the Cretaceous Period.

So it's quite possible these animals are more closely related to us than was previously believed, or at least, less related to dinosaurs.

That doesn't make any sense.

I hand-raised several jackdaws myself during my teen years. They were still blind when I started feeding them, and I let them free when they could fly. They flew around in the neighbourhood, and when I called their name when I was in the garden, they came flying to me.

The funny thing was that they had really distinct characters. The last bird I had was a real rascal: kept harassing the children at a school nearby for cookies, always tried to steal the cigarettes my father was smoking, stuff like that. Our neighbor at that time was afraid to wash her windows because the bird somehow couldn't stand it for some reason.

Unfortunately, they always flew away in the pairing season, so they stayed around for about a year or so.

There was a time when I had jackdaw whose tongue was "cut" by the vet. He started talking like parrots do, imitating the turkeys from my neighbors, slamming doors etc.

That one flew away on my birthday (can't even remember which one), but a year later, we heard some strange knocking on the window. Turned out to be my bird again, only with an injured wing and slightly more wild. A few months after the vet had fixed him up, he flew away again.

The moral of the story is that I certainly had a rich relationship with those birds. In my opinion even more than some of my friends who owned dogs (which I didn't have). The characteristics described in the article certainly don't come as surprise to me!

Wonderful!!! It is nice to see more and more information being published about this topic, being one I am personally very fond of!

FYI

One day my wife and I witnessed a duck funeral. We heard a commotion near our feeder and then saw three ducklings with their mother running and screaming down the hill toward the lake. The mother turned around halfway down the hill and went back up towards the feeder, only to retreat again after getting a look. We looked ourselves and saw a hawk sitting on the ground holding a duckling, which he proceeded to eat.

The mother sat in the lake with her three remaining ducklings and issued low, short quacks spaced every 4 or 5 seconds. Out of nowhere 20 other ducks swam to her. There wasn't another duck in the immediate area before. They formed a circle and one by one went up to her and touched her with their bills. A different duck each time. When they had all taken their turn, they swam away, leaving her with her there alone with her ducklings.

Beautiful image of the duck funeral. Thank you. I don't understand people who say humans are the only ones who have compassion, emotions, empathy, humor, symbolic language, etc. To say that requires a lot of just not paying attention.

One of the greatest tragedies that I will ever witness is the slow demise of the brilliant, endangered NZ mountain parrot, the Kea. The Kea, whose habitat was irreversibly altered with the arrival of humans and other mammals, will probably be extinct in 30 years. The teenagers used to hang around in large, mischievous gangs. They were capable of bolting and unbolting doors, forming teams to outwit and steal from the humans, and they would play games, such as slippery dip competitions on a steep roof.

Now they are often alone. I cry just to remember seeing one of them one day, sitting near a crowd of humans, all alone. It was staring into the distance, knowing full well that these humans were responsible for its starvation, and yet completely unable to give up the human environment, which was its best hope for food.

I have always regarded beliefs that humans differ from other animals in terms of kind, not degree, as at base religious. ("He has created thee a little lower than the angels.") They are always based upon the absence of evidence.

That said:

"For example, a recent study of Greylag Geese, Anser anser, found that flock members who observed a conflict involving either their partner or a family member experienced an increase in heart rate (a measure of distress) -- consistent with an empathic response [DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0146]."

This confuses sympathy with empathy. Etymologically, sympathy is feeling with another, while empathy is entering the feeling of another. Empathy is a kind of understanding. Consolation may involve either or both, but one's own distress interferes with empathy. Empathy requires a level of cognition that will be difficult to demonstrate without shared language.

there's no confusion on my part. if this reaction does not occur for non-relatives and non-mates in greylag geese, then how do you explain that?

I find it interesting that the control observation shows a high frequency of affiliation immediately after observation starts. That would suggest either a) that the ravens are reacting somewhat to the observer, or b) that the observer is less observant after a few minutes. Of course, the point of a control observation is to control for that in the test observation, and in that it succeeds. Still, one wonders about that.