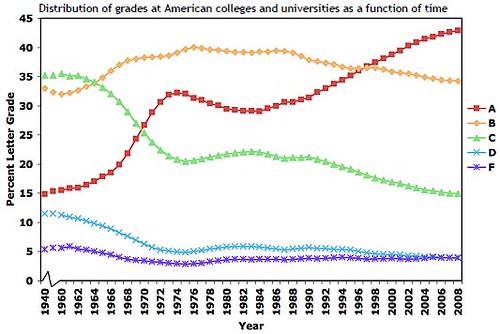

By way of Dr. Isis, we come across this post by Catherine Rampell about the rise of grade inflation in colleges:

Dr. Isis observes:

It's interesting that the real change in grading appears to have occurred in the period between 1962 and 1974, probably coinciding with the increase in conscription for the Vietnam War. After 1974 things appear to trend toward a return to baseline. Then in 1990, something new happens that drives grade inflation.

I think it's pretty obvious what happened: increased competition for graduate school slots put (and still puts) pressure on faculty to not give C's and to give more A's.

I don't mean that faculty received orders telling them to stop giving C's and start giving more A's. But admissions to decent post-graduate programs is so competitive that a B has a noticeable effect (lowers the GPA) and a C is the new F. Combined with students attempting to game the system to aid their GPA's (i.e., take 'gut courses'), and you'll get grade inflation.

But this model grade inflation requires that admissions to good programs becomes more difficult. Is it? If we look at MD's, between 1990 and 2005, the number of MD degrees awarded was effectively constant. Meanwhile, during that time, the number of biology degrees essentially doubled, and the total number of college graduates increased 86%.

If we consider MBAs awarded from the top 100 programs, by definition, you can't have an increase in the top 100 programs, and I haven't found any data suggesting that there is a massive increase in the number of MBAs awarded by these programs.

So I'll posit that a major factor in grade inflation is the increased competition for graduate school slots. This has led to B's and C's having a much stronger influence on students. At the same time, students have become more willing, when possible, to avoid courses that are graded harder. While it might seem that if everyone is getting high grades, that high grades don't matter. But if you don't have a high GPA, then you stand out as a poor student--there is a rachet effect that pushes grades upwards.

If we want to reduce grade inflation, then we have to stop making grades so critical for acceptance into increasingly selective 'good' graduate programs. Until then, grade inflation it is. The good news, I suppose, is that grades can't get any higher...

- Log in to post comments

I wouldn't be so sure of that. Around the time I graduated, my alma mater started counting A+ as 4.33 points for purposes of GPA calculations. I've also heard of colleges doing something similar with honors courses. So (numerically, at least, if not alphabetically) there is still room for grades to continue upwards.

Really fascinating to see A and C cross over one another there.

I don't know about most people, to me 'C' means 'average', but I guess it actually /can't/ mean that anymore. Is there anything to do other than to just accept it, to recognize a C as a failing student and a B as an average student, and to consider 'A' meaningless?

Honestly, I doubt that grad school (or similar professional schools like law or med school) is the key driver, simply because a relatively small proportion of the students continue into some sort of post BS/BA studies.

I'd be interested to see what the proportion of various majors is over time. Could this simply be due to more students just taking easy majors like English or Communication or suchlike, fully knowing that in private employment, nobody cares what your degree is in, so long as you have one?

"All about"? My limited experience at the top of the top of the heap doesn't jive with that at all.

In the 80s I was a math TA at Very Prestigious University, then went into industry, and a few years ago I was recruited to teach 2nd year calculus at a different Very Prestigious University. The curriculum had accelerated immensely in my absence. Instead of the expected year-long leisurely tour through vector calculus and elementary linear algebra and differential equations, all that was mostly jammed into one semester. That left nearly a semester to do some complex analysis and Fourier analysis and partial differential equations, which was third year material in my day.

I asked about this, and was told, haha, it was partly marching orders from the Engineering School from ten years before, but frankly, the students were all overprepping anyway, trying to outcompete each other on their way to getting admitting to Very Prestigious University in the first place, so it was an inevitable red queen's race anyway.

In other words, the students were objectively doing and learning more than their counterparts 20 years ago. Of course they deserve higher grades!

On the other hand, I eventually noticed that nearby Somewhat Significant University had a modified first-year calculus textbook for their premed program. It was a well-known calculus textbook, with the cover boldly stating that the content had been modified just for Somewhat Significant University. The difference? No trigonometry!

Actually, it looks to me like what is happening is that we are evolving into a "pass/fail" grading system. "D"s and "F"s have been pretty much constant since 1972, it's just that "C"s are becoming extinct.

Actually, I don't see a problem with a three-level grading system: "high passing" (A) for students who really apply themselves; "low passing" (B) for those who are just adequate, and "fail" (D) for the slackers. I really think that that is all the resolution that people are looking for when they look at grades, anyway.

As a college prof myself, I'm dubious. First, I think grade inflation is worse in the social sciences (my area) and humanities than in the natural sciences, and fewer of those students are thinking post-baccalaureate education (not none, just fewer), which by that theory should mean there was less grade inflation in those disciplines, not more. Second, grade inflation is higher at private colleges, and a whole lot of those private colleges are non-elite schools (like mine) that will have a smaller proportion of students planning post-baccalaureate education. Third, I don't think there's that much incentive for individual undergrad faculty members (and most of us at private colleges are purely undergrad profs) to push their students into grad school. There is some incentive, to be sure (it reflects well on me), but for most of the faculty I associate with there is a constant frustration with students who want to go on to law school, or for an MA in public admin, etc., who simply aren't up to snuff. And we just aren't interested in inflating their grades so they get that opportunity they're not really competent for--sending students to a grad program who then fail out does not reflect well on us. (Of course my sample is biased toward those faculty who I associate with, which means they tend to think like me and may not be representative of faculty overall.)

My subjective experience is that the real cause is twofold. First, students and parents have become more demanding and profs are no longer viewed with the respect they once had, so assigning lower grades is much likelier to result in challenges, which can quickly turn ugly. Just over the last 3 academic years my departmental colleague and I have had several really unpleasant incidents with students over grades and academic dishonesty. I take some pride in not adjusting my standards to avoid that unpleasantness, but I can understand why some faculty just give in to avoid the stress. Particularly if lots of other faculty at your school are doing it, it can seem pointless to be the lone person upholding the standards.

The second factor, I think, is ideology. There are certain faculty member, and my casual observation is that they tend to be disproportionately concentrated in the humanities and in sociology/social work, who worry about "punishing" students who are "really trying hard." They do give As for effort, but they have low standards even on that. That's not to say there aren't faculty in those fields with high standards (and I know some personally), but as proportions of the population, I'm pretty sure you'll find more of them there than in the natural sciences.

Let us not forget the rise in the use of adjunct faculty who lack tenure protection, a fact not lost on them or their students.

Here's an anecdote about grade inflation, for everyone's amusement and dismay. In grad school, the prof for whom I was a TA explained to me the standards for grading the take home midterm essay.

"A is for a student who does a really god job and answers the whole question. B is for a student who sort of misses the point of the assignment but still writes a pretty good essay. C is for a student who totally misses the point of the assignment."

"And," I asked, "what would be a D?"

"Oh," he said, shocked, "there won't be any Ds!"

So after grading them, he asked me how the students did. "Well, there weren't any Ds," I told him.

"Wonderful!" he exclaimed.

As if there was ever any doubt.

I think the change has been due to the rise in personal computers, and the ability of faculty to (a) create point-based-systems in Excel for calculating grades, and (b) being able to post notes, handouts, and grades online (via websites and Blackboard). Looking at the graph, 1988 is when things changed, moving in the rise of the internet.

Top flight graduate programs are well aware of grading differences between colleges. My daughter was told by a recruiter from one graduate school that his institution added .3 to the GPA's of students from her (academically challenging) undergraduate school, when comparing them to those of students attending state universities in the region.

I also would like to see this chart for different majors. In engineering, there has been some grade inflation as professors move from bell curve systems to fixed scales (i.e., 93%+ is an A, 85-92 is a B).

I have to say that my experience in grad school applications, though, agrees with @ancientTechie (#10). Graduate recruiters, especially in my smaller discipline, tend to be fairly familiar with the undergraduate programs, and will judge a 3.5 very differently, depending on the institution in question.

I think this shows exactly how subjective grades are (and have always been). As long as we understand that, and understand that they are a comparison, we will be fine.

There was a study released last year that showed that the disciplines that often do lead to grad schools (science, engineering) have had much lower inflation, with the lowest shift in pre-requisite courses. I think that math, science, and engineering pre-reqs come with almost a "set" lineup of material that needs to be mastered, and is harder to dilute.

Another factor in grade inflation is simply that the students, with the encouragement of faculty and administration, regularly game the system. Instead of having a fixed cohort taking a class and being graded, you have the worst students dropping out more often, objectively pushing the curve upwards.

Back in the day when C's were acceptable, students were more than willing to muddle through. Now they like to give themselves two or three chances, just so they can get an A or B. Drop out dates are set deliberately late enough--and faculty of course prefer not to deal with mediocre students anyway!--so that enough students get to find out they're in trouble in time. Self-selection for better students getting better grades is automatically enhanced.

As a side comment, while "gaming the system" is usually considered a pejorative, in the context of grades I'm all in favor of it, since frankly, I don't believe in grades all that much.

I would also be very interested in the effects of cheating on grades over time. My wife just went back to grad school in engineering, and cheating was rampant and penalties were minimal.

We're both 21st century college graduates, so we can't compare this to the "good old days" but I get the impression from the old timers that getting caught cheating once meant something. Nowadays, it seems to mean, "Try again, but don't get caught this time."

I was amused by #8's comment...but want to recap my own grading instructions to TAs in a large humanities survey, recently:

As are for the students who do really well, who understand and answer the questions by using evidence analytically to explain a thesis.

Bs are for students who learned the information, but provide only schematic and simple-minded analysis.

C's are for students who clearly made an effort, and who knew something, but couldn't pu it together.

D's are for the flailers who showed up and wrote something, but clearly didn't get it.

Fs are for the ones who had nothing to say.

There is room for Ds and Fs, therefore -- they added up to more than 10% of all grades at the end of the term -- but I also feel obliged to provide a pathway by which a diligent but uninterested student can earn at least a B-.

#5: In my high school (early 2000s), we had an acknowledged pass-fail system - we called the passes "A" and the fails "B+".

The average GPA was a hair under 3.8 unweighted, and the median was higher still. I did get one B+ in physics...the final was on quantum mechanics, but I'd skipped most of the preceding month of school, so what I read on the bus ride in was the chapter on relativity. Really, I deserved that one.

Why? It was a nice public school in a neighborhood where everyone's parents wanted to send their kid to an Ivy. Supply and demand.

But in college, for pre-PhD anyway, what matters is who knows you and is willing to vouch for you. Perhaps that's why the sciences have less inflation.

Very interesting article. Please visit www.draftresistance.org for more info on conscription.

According to a prof friend of mine, student evaluations have become very important. Primadonnas paying 40k per year blame the prof for their failings. "I got into this top school, so clearly you're to blame." So there's an incentive to make student's happy and let someone else bring them down to earth. Written on my iPod touch

I'd posted this before, on Isis' thread, but I think it bears repeating.

-- There might be self-selection. Students now have a lot more choices in how they structure a major, and there is much more specialization in the majors themselves. If you are in a science class it's pretty axiomatic that you WANT to be there, and so will work harder and be more talented at it to begin with.

-- For those on the grad-school track there is a huge incentive to self-select that way

-- If you do not plan on grad school then you can slack a bit, as nobody cares about your GPA when you apply for a job, nor does anyone care what your major was, unless you are in a science-oriented field

-- Getting a BA is just plain necessary to get any job, getting a 4.0 isn't (see above)

-- In the humanities especially, since nobody cares (there is no incentive) what your grades were, unless you plan on grad school (not many people do that), "mastering" the material is so subjective it almost doesn't matter. Honestly, were I grading papers (I am not an educator by any means, so take this with a grain of salt) I would not have the foggiest notion of how to grade them outside of "can't write a coherent sentence or idea" and "seemed to be conscious in the class." As well, there are people who make a lot of effort and don't do so well at it. (This would be especially true for students for whom English is a second language and the US a second culture).

Science is much more cut-and-dried and I think it's easier to tell if someone has learned it or not -- certainly it seems to me easier to pinpoint the part someone isn't learning on a calc test or physics quiz.

In other words, the students were objectively doing and learning more than their counterparts 20 years ago. Of course they deserve higher grades!

However, the point of a grade is not to know how much people know today compared with 100 years ago, but to discern how much people know against their peers.

I can tell you weren't around a university in the 1965-74 time period that Dr. Isis comments on. I was. Grade inflation was a result of the Vietnam war, when C's turned into B's and B's turned into A's. This had nothing to do with self selection into majors or faculty helping students get into graduate school -- except to avoid the draft. This was true at least until student deferments ceased to exist circa 1972. See it start to bend down in 1974, after we had pulled out?

Data point: the math department at one university had a policy, adopted by the faculty, that every student in a graduate-level math course got an A regardless of performance. That kept their deferment valid until they failed the PhD comprehensive exam, by which time they might have kids and avoid the draft that way.

Competition doesn't explain a change in the curve, particularly in a field like business where classes often don't meet on Friday so the students can start to party on Thursday night, or Education, where undergrad grades below an A are highly unusual. Competition should raise the curve, so students are better prepared for the GRE, etc, to get into competitive programs.

I also see zero evidence that students coming out of a college history class know more than I did when I took history in high school, or that K-8 teachers know more basic math than my teachers did.

"Try again, but don't get caught this time."

attitude caused by excessive cultural influence/demand of being 'successful' in business.

I've always thought that A for attendance, at least past the first year of grad school, was standard in all math departments. I've never actually bothered to find out.

I remember Iranian and Yugoslavian math/physics grad students that took an extra 5 or 10 years to finish their PhDs, without the usual departmental pressures applied to discourage them. Finishing could have meant going home to a very unpleasant situation.

I saw schoolwork at Columbia University undergrad level in 2000-2008 that was FAR better than anything that got A's from my circle of friends in colleges in 1967-75. To get into a good school now you have to work like hell, and learn a lot. Kids now get to college, and they already know a lot and are used to working harder than anyone in my generation ever did.

So of course their work is better!! Of course the grades are better!!!

I greatly mistrust story lines that start with "life was harder and better when I was young, and kids have it lots easier!"

How many AP courses did we take in high school? Kids now work harder, and learn more. God bless 'em.

Why can't the grades get higher? High schools offer 5 grades on allegedly 4-point scales for honors classes; I await seeing the first college to do that.

And, that gets back to #26. Kids get extra grade points for those AP classes. In addition, Mr. Drummond, AP admits it had let standards for AP classes get too lax.

"The good news, I suppose, is that grades can't get any higher..."

I wouldn't count on it. Consider the British exam system, where you used to get grades on the same A-D,F scale. Then people decided that it was getting too hard to distinguish between all the candidates with rows of As. Obviously you couldn't consider deflating the existing grades, so the "A*" was invented, to come above A. Apparently even that isn't enough any more, and the possibility of an "A* with distinction" is being mooted. You know, for those people who would have got an A thirty years ago.