Adam Frank has an op-ed at the New York Times that tells a very familiar story: science is on the decline, and we're living in an "Age of Denial".

IN 1982, polls showed that 44 percent of Americans believed God had created human beings in their present form. Thirty years later, the fraction of the population who are creationists is 46 percent.

In 1989, when “climate change” had just entered the public lexicon, 63 percent of Americans understood it was a problem. Almost 25 years later, that proportion is actually a bit lower, at 58 percent.

The timeline of these polls defines my career in science. In 1982 I was an undergraduate physics major. In 1989 I was a graduate student. My dream was that, in a quarter-century, I would be a professor of astrophysics, introducing a new generation of students to the powerful yet delicate craft of scientific research.

Much of that dream has come true. Yet instead of sending my students into a world that celebrates the latest science has to offer, I am delivering them into a society ambivalent, even skeptical, about the fruits of science.

This has prompted a bunch of discussion, up to and including my father calling me at 9pm to ask what I thought about it (I hadn't read it at that time, but it was on the to-do list). Most of what I saw on a quick scan of social media was resigned nodding, though there have been a few interesting additions here and there, such as the reliably thoughtful Timothy Burke questioning larger cultural context. I think he makes some interesting points, but at the same time, it's worth noting that the major changes he points to happened years before the polls Frank cites. So while it may be true that there was a great shift in societal attitudes between the era of the Manhattan Project and the end of Vietnam, I doubt that can really explain what's happened since 1982.

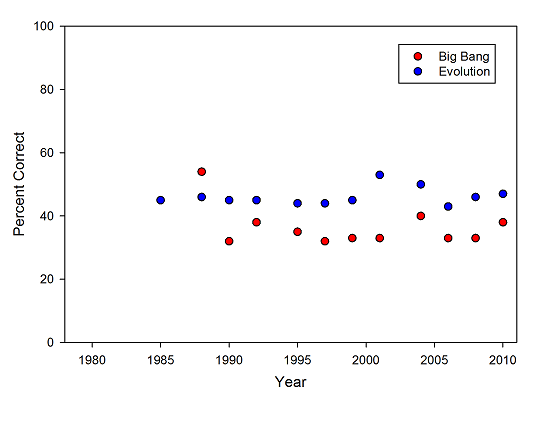

But while I dabble in public intellectualizing, I'm really a charts-and-graphs guy at heart, so let's take a look at the data. I don't actually have the exact polls Frank refers to, but the NSF helpfully publishes a "Science and Engineering Indicators" report every so often, and the appendices offer a wealth of relevant data in convenient spreadsheet format. These include, in Chapter 7, some time series of poll questions covering roughly the time span of interest, and some of the same issues. If we pull out the data most closely related to the "creationist" thing, and make a graph, we get this:

These are the percentage of people correctly answering the true-false questions "The universe began with a huge explosion" and "Human beings, as we know them today, developed from earlier species of animals." If you need me to tell you the correct answers to those, you're reading the wrong blog.

That shows... not much of anything, really. The numbers start fairly low, and more or less stay that way. I didn't put error bars on these, but the one-standard-deviation uncertainty would be around plus or minus 2%, so the only thing that would be at all difficult to write off as statistical noise is that first Big Bang point. Lingering effects of Carl Sagan, maybe?

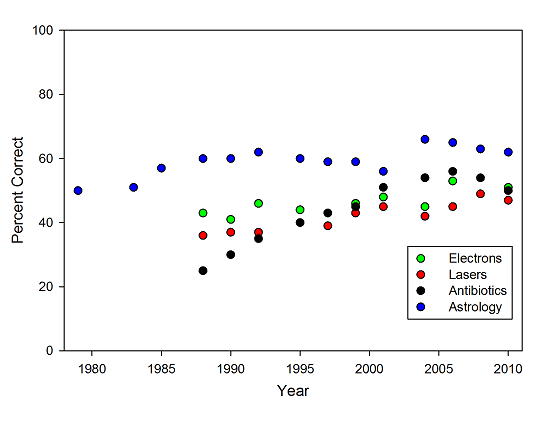

Of course, you can dip into the same data set, and come up with a graph that tells a different sort of story (which is also the "featured image"):

The percentage of the population correctly answering questions about electrons, lasers, antibiotics, and astrology.

The percentage of the population correctly answering questions about electrons, lasers, antibiotics, and astrology.

These points give the percentage of people correctly answering the true-false questions "Electrons are smaller than atoms," "Lasers work by focusing sound waves," "Antibiotics kill viruses as well as bacteria," and from a different part of the poll, the percentage saying that astrology is "not at all scientific." All of these have a distinct upward trend over the thirty-odd years of the poll.

So, what do we really have, here? On one set of questions, we have a story of stagnation, but on the other, a tale of modest progress. Is this really indicative of a collapse in the status of science? It's useful to ask what these sets have in common-- in the cases where we see stagnation, the questions are bound up with issues of politics and identity. A professed belief in something like creationism is one of the essential markers of a particular brand of political conservatism. As a result, even people who know the scientific answer are prone to giving the answer they're "supposed" to give as a member of a particular political affiliation. And the number of people who self-identify as political conservatives, like the number who deny the Big Bang and evolution, is pretty consistent over the last thirty years.

Meanwhile, on issues that are pretty much neutral, politically-- at least, I'm not aware of a powerful large-electron lobby pushing the idea of sound-powered lasers-- we see a story of slow improvement in public knowledge. The improvement on the antibiotic question since the 80's is really striking, though the last couple of points are a little troubling, and might reflect collateral damage from the anti-vaccine movement. Which is, as Kevin Drum is fond of pointing out, pretty much the same story we see when we look at math and reading test scores over the same period-- despite a pervasive narrative of decline, scores are actually slowly improving.

Is the status of science really collapsing? I don't know that I'd be comfortable saying that. There are certainly plenty of examples of a degradation in the rhetorical stance political figures take toward science, but then there's been a degradation in the rhetorical stance political figures take toward just about everything. I'm not sure why you'd expect science to rise above that.

Is the status of science as high as I would like? Absolutely not. But then, I'm not sure it's actually reasonable to expect science to be held in as high esteem by the general public as by those who choose to pursue science as a career. But that's not really the issue-- the question is whether we've fallen off from some golden age when everybody listened raptly to the best science had to offer. But that's not really clear from the polling data we have, or the plural anecdotes from farther past. After all, as depressing as it may be for forty-odd percent of the population to want to align themselves with a creationist position (whether from honest belief or out of tribal identification), that's probably an improvement from the days of the actual Scopes trial. Which, it should be noted, Scopes lost, unlike the several more recent cases where teaching of creationism has been soundly rejected by the courts.

And stories of scientists needing to stand up for the worth of their discipline against crass politics are nothing new-- people have been (falsely) quoting Faraday as defending electrical research with the line "someday, you may tax it" for decades. And from the height of the supposed golden age in the 60's, there's the famous story of a physicist asked what a particle collider would contribute to national defense retorting that "it makes us a nation worth defending."

To the extent that there was a golden age of respect for science within living memory, I suspect it was a historical accident. Science, like many other things (international sports, cultural events, third world revolutions) was a useful venue for a proxy fight during the Cold War, and some savvy scientists grabbed onto that and rode it about as long as they could. There was a happy alignment between the goals of national politics, powerful business interests, and scientists, and for a while the scientists did very well from that. And, it should be noted, in areas where scientists continue to be useful to wealthy and well-connected businesses-- telecom, drug development, biotechnology-- they continue to do very well, and win far more battles than they lose. It's the areas where the interests of science cut against the interests of a powerful political class (the culture warriors of the Right) or powerful business lobbies (climate change) that they run into problems. And that was always the case, even when science was supposedly riding high-- look at the rocky start of the environmental movement, or medical research on tobacco. I don't think the underlying issues are really all that different than they were in the past-- the state of science, like the poll numbers, is more or less as it ever was.

I'd like to offer a slightly different explanation for Adam Frank's narrative of decline, a psychological one. The post title is a play on the old joke about the Golden Age of science fiction being twelve, that being the age when readers are perfectly positioned to have their minds blown by whatever they run across. They'll forever remember those stories as the most awesome thing ever, and nothing they encounter as adults will ever have quite the same sense of sheer joy and awesomeness.

I think something similar, if a bit darker, is at work in Frank's op-ed. The difference between 1982 and 2012 is not that the public's understanding of science has gotten any worse, it's that Frank has gone from his twenties to his fifties. When you're an undergrad science major, you're perfectly positioned to see science as, well, SCIENCE! It's a repository of wonder, with boundless potential for the future.

Twenty or thirty years later, after a bunch of great ideas that blew your undergrad mind have failed to pan out, and after years of writing essays and columns and books have failed to move the public understanding of science significantly, well, things look a little bleaker. And it's easy to mistake the change of perspective wrought by decades of frustration for a narrative of decline. When you're forty, or fifty, and feeling unappreciated, things look bad. This is exacerbated by the modern 24-hour news cycle with its endless parade of hucksters trying to make everyone angry and frightened, but it's probably just about inevitable even with a healthy media culture.

There's also a bit of loss aversion here, as well-- recent setback may be, in the big picture, small steps back compared to a long history of forward progress. But it's well documented that people fear and resent a small loss in what they already have more than they value a larger future gain. The combination of the two, after thirty years of work, can feel pretty terrible-- while objectively, there might be progress, it was supposed to be even better, and that can be maddening.

I understand the frustration, really I do. I'm about ten years younger than Frank, but I recognize a lot of the feeling. Things I thought looked bright and hopeful have fizzled out, and there's a lot that's frustrating about modern culture, and the state of science, and my career. By any reasonable standard, I've done very well for myself, but there are days when I feel like everything is a giant waste of time-- especially this blogging thing, which feels like screaming into a void-- and I want to hang it all up and go herd goats.

But then, I have to remind myself that there's a lot about modernity that's awesome, too-- the Internet, for starters, is vastly cooler and weirder and more fascinating than anything I would've dreamed of as a naive undergrad. And that there were a lot of things that sucked in the past-- yeah, it sucks that powerful right-wing politicians make hay by claiming climate change is a "hoax," but really, how much different are they than, say, James Watt back in the 80's? Reagan asserting that trees cause pollution? (To pull a couple of examples from childhood memories.) When I was a kid, you could still find people denouncing the phaseout of leaded gasoline as a form of fascism (well, communism, because it was the Cold War, but one of those European -isms), and that didn't fly in the face of business interests anywhere near as much as climate change does.

So, is science really in decline, losing the culture wars? When I can step back and look at it calmly, I have a hard time saying that it is. Yeah, we're on the short end of a lot of rhetoric, but at the same time, a lot of things are trending the right way. More people are paying attention to healthy eating and responsible environmental practices, smoking in public is way less acceptable than it was. You see more efficient cars, and lights, and appliances of all sorts coming around and getting adopted. Home solar panels have gone from being a nutty hippie affectation to a home improvement service advertised on sports talk radio. And the picture's even better at the level of basic science-- the list of stuff that we routinely do now that was thought to be impossible when I was a kid is just mind-blowing. Mars rovers! Extra-solar planets! Feathered dinosaurs! Ten-meter atom interferometers!

(And then, of course, there are the vast improvements in the political status of any number of underprivileged groups, and the dramatic economic advancement of large swathes of the globe. Either of those by itself would be worth stagnation in science-- the fact that we've made progress in all areas is just awesome.)

Again, there's plenty that's bad, I'm not going to deny it. But just because we're not winning as fast as we'd like doesn't mean that we're in decline. Though frustration might make it seem that way at times.

Did you try to do a linear regression for the data in your 2nd graph? There's a clear upward trend for antibiotics (and, maybe, for astrology). But for electrons and lasers? Meh.

In any case, I'm not sure why we should expect any improvement over the past 40 years in any of these responses. Aside from the increased attention to climate change (not, under the political circumstances, an obvious "win"), what development over the past 40 years might possibly be responsible for such an improvement?

Regression slopes:

Electrons: 0.5 +/-0.1, R^2 = 0.7

Lasers: 0.55+/-0.07 R^2=0.88

Antibiotics: 1.3 +/-0.2 R^2=0.87

Astrology: 0.36 +/- 0.09 R^2-0.58

This country has always had a lunatic fringe on any of a number of topics. Velikovsky found a sizable audience for Worlds in Collision in the 1950s, the supposed "golden age" of science in this country. Around the same time, Heinlein was complaining about the rarity of weekly astronomy columns in newspapers, which invariably published a daily astrology column. That's in addition to the various religious nut-fringe types who pop up in American history now and then.

What's changed is that the spokespeople for the nut fringe movements have bigger megaphones than their counterparts of the mid 20th century. The internet works both ways here; it gives people like Alex Jones a platform to push their views to the sort of person who would believe the sorts of things an Alex Jones would say, without being interrupted by other folks who would quite reasonably say, "What a maroon!" It also means that elected politicians who espouse such views get an audience far beyond their constituency. The tendency of the American press to run "Opinions Differ Regarding Shape of Earth" type stories also contributes. Lots of people are pointing out that such politicians and conspiracy mongers are, indeed, full of it. But the debunkers are often ignored (I have heard secondhand reports that on certain political sites linking to Snopes.com is an offense punishable by banning).

It belatedly occurs to me that for completeness, I ought to give results for the other two fits, as well:

Big Bang: -0.3 +/- 0.3, R^2 = 0.14

Evolution: 0.09 +/- 0.11, R^2 = 0.07

I basically agree with the points about the Internet and media culture. I suspect that there's a sense, though, in which the fact that the spokespeople for nuttiness need bigger megaphones is a Good Thing, but I need to think about it a bit more. I wasn't able to articulate it clearly on a first pass, and I have other stuff I need to do now.

Let me quiblle!

Did the universe really start with a "huge explosion"? If I saw that question on a true-false test, I would be frustrated because I know the answer is "true" but I'm not sure the Big Bang was technically an "explosion" in the normal sense of the word.

From an article on Livescience.com

"If it were an explosion it would have a center," said physicist Paul Steinhardt, director of the Princeton Center for Theoretical Science at Princeton University in Princeton, N.J. "We actually observe that everything is moving away from everything else. It's really about an expansion of the universe ." "

Let me learn how to spell "quibble" correctly!

I think it has as much to do with cultural "pushback" by people who just get overwhelmed with the sheer amount of information we are all bombarded with. Saying "Well, I don't believe THAT!" is sometimes just a way to take a deep breath and create a little psychic cushion to minimize the constant buffeting.

I'm a science-appreciating type guy but I've found that the more minutiae I learn about, e.g., astronomy or particle physics, the more I want to configure my own formulations for how this stuff really works.

I also sometimes get frustrated at the way concepts that I *think* I understand are either misprepresented on some of the popularizing TV shows, or make me feel that I never understood them in the first place.

Experts? We don't need no stinking experts!

"The universe began with a huge explosion"

False.

1. As already mentioned Big Bang wasn't really an explosion.

2. It wasn't "huge" since the volume was infinitesimal.

3. We have no idea how the Universe began, Big Bang theory only tells us that as we extrapolate into the past the Universe gets progressively smaller, denser and hotter. There is no way to know how far into the past this extrapolation is valid and little reason to believe that it makes sense to take it all the way to the limit in which all of the Universe is restricted to an infinitesimal point of infinite density and temperature which constitutes some sort of " beginning" whatever that means.

Scientific models are great but they are only reliable in the regimes in which they were experimentally verified. Extrapolations far beyond those regimes are good as first guesstimates but they should not be presented as scientific dogmas.

Cyclic models and eternal inflation are just 2 examples compatible with current data in which Big Bang is not the beginning of the Universe.

Yes, eternal inflation proponents presumably account for the 20-point drop between the first and second Big Bang data points, which are at roughly the right time for inflationary models to have reached the public consciousness. I'm sure that's it.

Well, if they can't even pick a proper question there is absolutely no reason to think they were able to pick proper unbiased samples as that is much more tricky. And if the poll is shit who cares why the data came out as it did, it could all be sampling errors.

Unfortunately, Science has descended to the realms of dogma. If you want to suggest an alternative to the currently accepted "models" in use today, you are shot down and classified immediately as a "crank" and "wacko", irrespective of whether you are a "crank" or "wacko" or not.

In my engineering undergraduate days, it was regularly stressed that "models" are just models and are not reality itself. Models are useful because they provide a simplification of the real world in which we can ignore certain phenomena for the purposes of the task at hand. Computer models being the most prone to being taken too seriously and getting the wrong results or conclusions.

What we see today is that the "models" in use (or being investigated) are being transformed into "reality", when the reality is that we truly don't know. In engineering, we used "magic" numbers at times to simplify our calculations to get something that worked. When one looks at say the state of HEP and the plethora of "fundamental particles", one starts to realise that these researchers are forgetting one very fundamental fact of their research, the observations they are observing don't actually "prove" anything true. They may confirm a prediction from their model, but that is all. The model/s being used are so full of "magic" numbers that they take as being reality, that one wonders what they are teaching them during their training.

I have seen at least two quite different alternative models that predict the fundamental constants that are measured by experimental results. In one case the author actually describes it as a model and that even though it works, it is not to be mistaken for reality.

The reality is, that we just don't know. We make assumptions about many things and live by them as if they are reality. We all carry models in our heads about how the world works. We too often forget to ask the simple question "What if we are wrong in our base assumptions?"

For Eric Lund above, the "lunatic fringe" does include such luminaries as Galileo, Copernicus, et al. Just because someone has an idea that is not compatible with the prevailing dogma doesn't make them "wrong" or "lunatic". Velikovsky made a number of solar predictions that have since been validated, temperature on surface of Venus, Solar charge, Jupiter radio transmission. I have read some of his works and he makes various claims that go against the accepted models. The question to be asked is "Are the observations he used to get his model, explainable by the standard models in use?" If they are, what additional observations can be used to separate the models? If they are not, why not?

Just because a model is different, doesn't mean that it should be rejected out of hand. It needs to be investigated for it merits. If it has none, then reject it.

My initial comment was not meant to be a reflection on why there were changes in people's opinions but just a reflection of how annoyed I would be if it that question showed up on a questionnaire I had been asked to complete.

In regard to modelling: Science and engineering would be needlessly complicated if every discussion of model results had to be followed up by a disclaimer that the model isn't actually reality. For example:

"Our model, which may or may not reflect reality, gave a prediction that current levels of benzene in the groundwater (which, by the way, may or may not reflect reality because we couldn't sample every drop of the groundwater and had to use statistical sampling techniques) will drop from their current levels to within the regulatory limits within 5 years, but since it is just a model, we can't be sure that this prediction is correct. Oh, and since the regulatory limits were developed based off of their own models, we can't be sure that reaching this level will actually accomplish anything."

I think that's a little wordy.

Problem with not using a disclaimer is that

It's a model. (our current guess - hypothesis - theory)

goes to

It's a fact. (This is how it works - it's what true - no doubts about it - and anyone who doesn't believe us is a kook, crank, fool or lunatic - as an example, see the arguments between string theorists and non-string theorists)

Where then is the science in this?

The overall average of all those data points looks perilously (parlously?) close to 50%. That's what you would score by randomly guessing true-false answers. Gaaahh.

A thing that didn't make it into the post-- and yes, there's stuff that didn't make it into this very long post-- is that on the non-controversial question, the US leads the world. Yeah, the percentage of Americans who know that lasers don't involve sound waves is consistent with guessing the true-false answer, but we're blowing most of the Asian countries away on that. (at least as of about 2010, when I last saw that graph). Ditto the relative sizes of electrons and atoms.

Wouldn't the "size" of an electron depend on it's de Broglie wavelength and in some cases an electron might be "larger" than some atoms.

there are days when I feel like everything is a giant waste of time– especially this blogging thing, which feels like screaming into a void– and I want to hang it all up and go herd goats.

Hmm, I kind of feel bad about this. Is there anything we as readers can do to help or is it just something that's periodically inevitable?

That said, I'm sure you'd be good at herding goats, though it might not end up as any more enjoyable than blogging.