"If the Universe Is Teeming with Aliens... Where Is Everybody?" -Stephen Webb

As egocentric as we are, we know that not only are we but one planet of many orbiting our Sun, but that when we look up in the heavens, every point of light we see is another chance -- another opportunity -- for planets, for life, and even for intelligence.

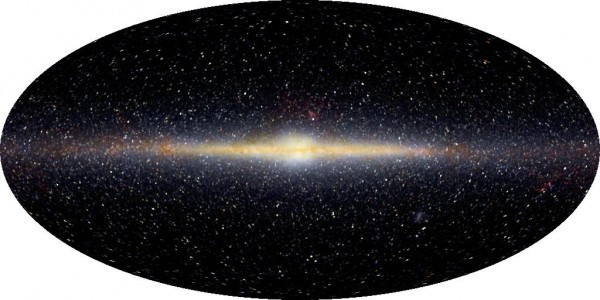

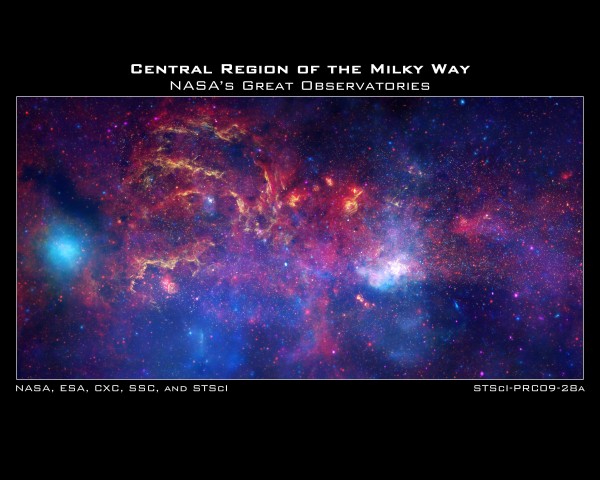

With hundreds of billions of stars (visible here in infrared wavelengths) in our galaxy alone, we have many, many chances for life to have evolved similarly to how it did here on Earth. With hundreds of billions of galaxies in the Universe, it seems unfathomable to us that we would be alone as the only self-aware, intelligent, sentient lifeforms in the Universe.

The question atop -- where is everybody -- is known today as Fermi's Paradox.

Is there really anything paradoxical about it at all? Let's take a look.

This is Earth, our home, and (so far) the only place we know of that harbors life in the Universe, much less intelligent, sentient, self-aware and (possibly) capable-of-communicating-with-alien life. We assume that if there are intelligent extra-terrestrials out there, they'll be made of the same chemical elements we are. Not because it's the only way to store information, or because we think any other methods are prohibitive, but because this is something we understand, and we know at least one way that it works.

And if it works this way here, for us, perhaps it works elsewhere, too, for someone else. Other than the right elements (which are all over the galaxy and Universe by this point), what we need is actually pretty simple.

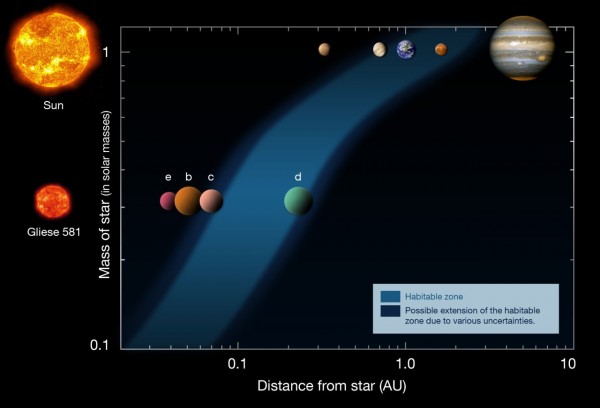

We need to be the right distance from the Sun in order to have liquid water. In other words, we need the temperature to be a particular value. If it were too cold, everything would freeze, and if too hot, everything would boil (and too many chemicals would denature).

Fortunately, we're not speculating about this like Frank Drake had to fifty years ago. We know of thousands of planets that orbit around other stars now!

As best as we can tell -- extrapolating what we've discovered to what we haven't yet looked at or been able to see -- there ought to be around a trillion planets in our galaxy, and somewhere around ten to a hundred billion of them are candidates for having liquid water and Earth-like temperatures on their surfaces!

So the worlds are there, around stars, in the right places!

What about the building blocks of life?

Believe it or not, these are unavoidable by this point in the Universe. Enough stars have lived and died that all the elements of the periodic table exist in fairly high abundances all throughout the galaxy.

But are they assembled correctly? Taking a look towards the heart of our own galaxy is molecular cloud Sagittarius B, shown above. In addition to water, sugars, benzene rings and other organic molecules that just "exist" in interstellar space, we find surprisingly complex ones.

Like ethyl formate, above, the compound responsible for the smell of raspberries, among others. So with tens of billions of chances in our galaxy alone, and the building blocks already in place, you might think -- as Fermi did -- that intelligent life is inevitable.

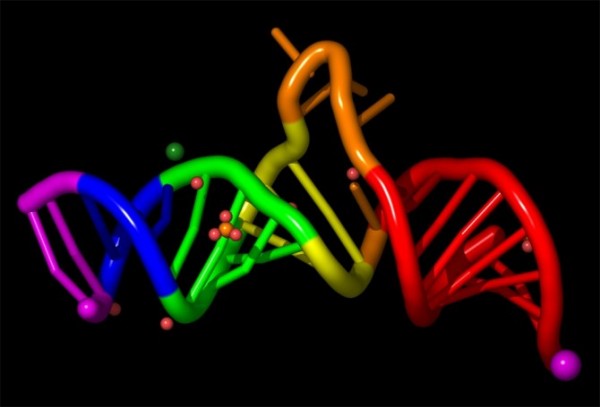

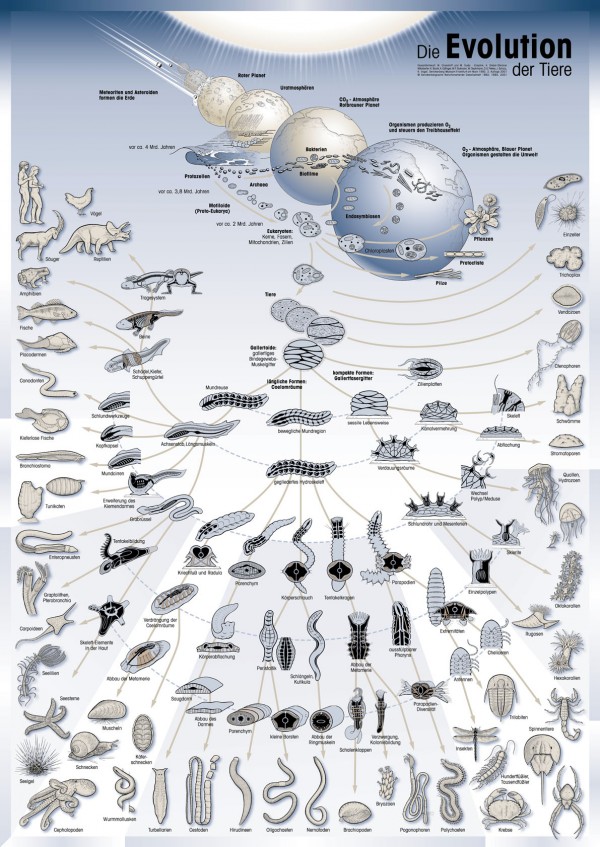

But there is a big difference between an organic molecule and an intelligent lifeform. On Earth alone -- the one place where we know it worked -- it took over four billion years and a slew of unlikely events to bring us about.

What was it that needed to happen, and what are the odds of it happening? Let's go through it, both liberally and conservatively, and see what we get.

First, we need to make life from non-life. This is no small feat, and is one of the greatest puzzles around for natural scientists in all disciplines: the problem of abiogenesis. At some point, this happened for us, whether it happened in space, in the oceans, or in the atmosphere, it happened, as evidenced by our very planet, and its distinctive diversity of life.

But thus far, we've been unable to create life from non-life in the lab. So it's not yet possible to say how likely it is. (Although we are taking some amazing steps.) It could be something that happens on as many as 10-25% of the possible worlds, which means up to 25 billion planets in our galaxy could have life on them. (Including -- past or present -- others in our own Solar System.)

But it could be far fewer as well. Was life on Earth likely? Or, if we performed the chemistry experiment of forming our Solar System over and over again, would it take hundreds, thousands, or even millions of chances to get life out once? Conservatively, let's say it's only one-in-a-million, which still means, given the conservative end of 10 billion planets with the right temperature, there are still at least 10,000 planets out there in our galaxy alone with life on them.

And we need that life to stick around for -- as best as we can tell -- at least for billions of years, in order to evolve into something interesting enough to be considered intelligent. Large, specialized, multicellular, tool-using creatures are what we're talking about. So while, by many measures, there are plenty of intelligent animals:

We are interested in a very particular type of intelligence. Specifically, a type of intelligence that can communicate with us, despite the vast distances of the stars!

So how common is that? From the first, self-replicating organic molecule to something as specialized and differentiated as a human being, we know we need billions of years of (roughly) constant temperatures, the right evolutionary steps, and a whole lot of luck. What are the odds that such a thing would have happened? One-in-a-hundred? Well, optimistically, maybe. That might be how many of these planets stay at constant temperatures, avoid 100% extinction catastrophes, evolve multicellularity, gender, and eventually learn to use tools.

But it could be far fewer. Even one-in-a-million seems like it might be optimistic; I could easily imagine that it would take a billion Earths (or more) to get something like human beings out just once. Because at the end of the day, here's what we need to see.

We need to see the sky in radio wavelengths, and we need for other aliens to have broadcast signals in those wavelengths we're looking for. (Other methods may be possible, but this is one example we know would work.) In order to do that, we need for them to build transmitters of some variety,

and for us to have build detectors of some variety.

We have both of those capabilities of course, but how many other worlds do? If we take the optimistic estimate, perhaps 250 million worlds are out there capable of communicating with us, in our galaxy alone. But if we take the conservative estimate, above, there's only a one-in-100,000 chance that our galaxy would have even one such civilization.

And we're not done yet.

Because human haven't been around forever, and we won't be around forever. Neither will humanity's equivalent on another world. Whether it's nuclear war, natural disasters, or a slow poisoning of our own environment, at some point there will not be humans on Earth any longer. For what percent of our star's lifetime will humans be around? Or, of all the civilizations that may have existed over the history of the Universe, what are the chances that there are aliens out there now, capable of communicating with us?

Humanity has only been around for a little over a hundred thousand years, or about 0.001% of the history of the Universe. Optimistically, perhaps we will thrive for another million years before we either evolve into something completely different or destroy ourselves. But pessimistically, we may only be around -- in our able-to-communicate-phase -- for a few hundred years.

Taking the million-year estimate and our prior optimistic figure, that means there may be as many as 25,000 civilizations ready to communicate with us right now in the Universe. (Clarification: this is 25,000 civilizations in our galaxy, which are the only ones in the Universe we'll be able to communicate with on sub-million-year timescales.)

But taking the pessimistic number and applying our pessimistic estimate? There's only about a 10% chance of there being one Earth-like world, today, with a species like us on it, in the entire Universe.

Regardless of whether the optimists or the pessimists are closer to being right, there is no paradox. If the pessimists are right, it's because there isn't anybody out there for us to talk to. And if the optimists are right, there's still almost nobody out there for us to talk to! 25,000 civilizations in our galaxy, right now, still means that the nearest one is probably hundreds of (if not closer to one or two thousand) light-years away.

But we have to look. There's too much to know, too much to gain, and too much to learn for us to not ask these questions. Some would have you fear the unknown, but any civilization that talks to us will likely have been around -- as you can tell from the estimates -- in a technologically advanced state for thousands or years, if not hundreds of thousands (or more). When you think of all the social and political problems that we've solved (and are solving now) just over the past few hundred years, and the hurdles we have coming up over the next few hundred (including population, pollution, energy, resource management, human rights, and more), any civilization that talks to us has likely already solved those problems.

So where is everybody? If they exist at all, they're very far away. But life, in some form or another, is sure to be close by, and we wouldn't be doing justice to the curious, investigative nature of humanity -- the very nature that's led us this far -- if we stopped looking now.

After all, as Carl Sagan so beautifully said,

I guess I'd say if it is just us... seems like an awful waste of space.

- Log in to post comments

I've always thought that the calculations about technological civilizations (which could conceivable communicate or at least broadcast) Out There were insanely optimistic about the lifespan of high-tech civilizations. One generation, you're building radios; a generation or two later, nuclear bombs. 100,000 or 300,000 or a million or a billion years to get to that point, depending on when you want to start counting; and perhaps 300 years until we bomb each other back into the Stone Age if not the Protozoic Era.

Two relevant thoughts and a side comment. First, it seems to me that all of our speculation is pretty much blue-sky stuff. Two inescapable facts are that (a) we have not been contacted in any meaningful/recognizable fashion, and (b) we know of only one place in the universe where there is life. With one data point, you can draw literally any graph. As the AC said in Asimov's classic story "The Final Question," there is insufficient data for a meaningful answer. After all, our planet might have taken an unusually long time to develop life. Most exoplanets could have life--perhaps even ecosystems we could use if we could just get there--but intelligence might be rare. Or perhaps there are countless planets at the level of Ancient Greece, but without resources to reach the Industrial Age and have a big enough energy surpluses to build big transmitters. Perhaps, perhaps, perhaps... Fun and interesting to speculate, and we certainly have to keep looking!

Second, if someone has developed a practical interstellar drive, we might have reason to be afraid. After all, they might not be coming to take resources away, but just to expand for expansion's sake: the more places you plant your gene-equivalents, the better your chances for species survival. 1930s Germany wasn't so crowded that lebensraum was an actual necessity, but the notion sure caught on, didn't it?

Final thought: Greg, this is one of my favorite blogs: I surely hope you have a broader readership than the number of comments would indicate. You're more interesting, articulate, and informative than a fair few people who post over at scienceblogs.com, and you don't go out of your way to be snarky like PZMyers (blessings of the IPU upon him). Thanks for a truly nifty blog: I hope to still be reading, enjoying, and learning from it when I'm old and grey (which is not as far off as it seems it should be)!

25,000 total for the whole universe appears to be excessively conservative.

Frank Drake type estimates about the number of sentient races in this galaxy alone are, avoiding four letter words, pseudo scientific self indulgent intellectual exercises that amount to pretty much nothing. Any set of numbers can be selected as the starting point and any answer that you want can be conjured up from those numbers.

Bearing in mind that there isn't even a single civilised government and country on Earth, governments varying in type from elective oligarchies at best to theocratic tyrannies and anarchies at worst, the answer to Fermi's paradox could very well be quite simple and very unflattering.

I'll accept your pessimistic limit - but some of your optimism is a little too shy for me.

Life from non-life, given the chemical mix as advertised, might well approach high percentages: 80%+. The reasoning for such a high figure is the faint traces that (I understand) suggest that life may have started several times as the Earth settled down and the accumulation of planetary material trickled to a stop.

Taking the initial-life-to-intelligence process apart, we have the (fairly) stable conditions requirement, evolution of complex life, and evolution of intelligent life. The stable conditions question I'm not very qualified to judge; but let's call it, since we're on the optimistic end, 25%. Given those stable conditions, my understanding of evolution is that it is not merely true, it is inevitable, and complexity arises naturally with time. Wild optimism says 100% and experience beats it on the head and says 80%. Intelligence is a much less obvious step; again we are supposing stable conditions for a few billion years which should produce a rolling over of various species with different strengths. This one is a real stab in the dark; again the optimism pushes the answer up to 25%. Giving me (0.25 x 0.8 x 0.25 = 0.05) 5% chance of intelligent life appearing.

Like Markita I think an average of a million years for an intelligent inventive species is a very strongly optimistic position. I would push that one down to 100,000 years, to account for "infant mortality" - communicating civilizations that don't make it to a thousand years.

Taking the hundred billion water planets I then get my top-end all-optimistic estimate at 40,000 current civilizations in our galaxy. Not so different to your figure after all.

And, I'm an idiot. I didn't mean to call you by someone else's name, Ethan.

One assumption that has never made much sense to me is that radio would be the preferred - or even optional-method of interstellar communication. Even at our relatively primitive state, we know of certain quantum effects which appear to propagate instantaneously regardless of distance. Granted we don't yet have the foggiest as to how these could be used to encode information-but time may tell.

Dolphins and whales may qualify as intelligent but they dont need fire, clothing, shelter, or radio transmitters. Many of our capabilities developed as a way to offset our natural inadequacies. How common is that? .

It's both exciting and depressing to realize that the emergence of life somewhere else in space or time is practically a certainty, but we are condemned to never see it. Tantalus would weep.

And, I'm an idiot. I didn't mean to call you by someone else's name, Ethan.

The premise behind the "paradox" is not just that intelligent life will arise elsewhere, but that, having arisen, it will then inevitably spread. Ultimately, there's little to hold it back besides the speed of light. So the question then becomes... why aren't they here already?

Of course there are a number of implicit assumptions in that formulation that one could poke at. Personally, I like to think that for a civilization to even reach the starfaring stage, it much first shed most of its self-destructive rapacity -- which means that it will expand very slowly, if at all.

But, like everyone else, I have no actual data on the subject.

I always get annoyed with the "This is the year of life on earth and we are now at the end of December" even when David Attenborough does it. It's more like June or July with another couple of billion years to go. Unless, of course, Harold Campling is right, in which case I will apologise to Sir David.

It's nice to read an update on the estimate after having discovered so many planets. The first time I heard of it was in Carl Sagan's Cosmos, when we knew no planets out of solar system. One unknown variable less in the big equation, I suppose. Let's find out more about the other variables!

This mental masturbation is so beautiful to watch... like a train wreck. Crichton already answered it, much better than I could - http://wattsupwiththat.com/2010/07/09/aliens-cause-global-warming-a-cal…

We're already abandoning the sort of wide-beam analogue radio technology which would be detectable by someone "out there", and we've only been using it for a century or so. I also profoundly unconvinced that a human-like intelligent species would necessarily develop such technology in the first place - it took a very particular combination of cultural, economic and geological factors to kick off the Industrial Revolution.

Abiogenesis is still a relatively young field. From what we know of evolution and chemistry, one likely path is from simple self-assembling molecules to self-assembling and replicating molecules to self-assembling and replication with modification. As the chemicals become more complex they may develop alternative methods of replication and these chemicals in turn would accrete changes which may ultimately lead to some life forms. Personally I think the demonstration of self-assembly and then self-assembly and replication would be an enormous first step. Perhaps we can even show self-assembly+replication+modification, but I doubt we can show much more than that - after all, life is likely to have taken many millions of years to get started.

:)

http://xkcd.com/638/

Ethan, can you enlighten us as to how you arrive at your 10-100 billion estimate of planets with liquid water?

I get a similar estimate by taking the Kepler data and scaling up to the number of stars in the galaxy. Then I scale up by a factor of 360 or so, since Kepler misses most planets (it only catches ones that eclipse). I get around 40 billion planets (give or take a LOT). I'm curious as to what you did.

(BTW, I am a high school astronomy teacher. Your answer will definitely make it into my astronomy class next year.)

Personally, I believe that Zuckerman and Hart have it correct in their book of essays: Extraterrestrials: Where are they?

Too many problems with a galaxy teeming with life and yet no one here yet.

For about $8 used, a very good read and I recommend it.

@MadScientist #15 -

...in a laboratory the size of a planet.

But at least, in our 10-orders-of-magnitude smaller experiments, we can pick and choose some potentially favorable conditions - and if we guess right, we might advance one more step.

Id say this:

Let's set a point where life definitely DID NOT exist and work from there (using a 4 billion year yardstick for life w radio communicating properties to develop):

It's pretty much certain that the big bang up to the first generations of stars simply did not provide enough resources for planets & life to form. Give it a billion or 2 years before metal rich stars are created and die and now were almost a 1/4 the way to where we are now.

Say around 4 billion years is a good starting point from where life started radio intelligence from the big bang then there are possibly 3 cycles of life that could have been processed by the time we have been created. Life that still exists from the first 2 cycles (if it can be done) would obviously be far more advanced than us.

But how about us now?? assume we were in the initial "first cycle" of radio intelligent life in our own galaxy?? Our ability to send and receive would be simply limited by the speed of light!!

My point is this: just as there is a cosmic microwave background ....perhaps in 10 billion years all of the intelligent life--whether extinct now or not--will be permeating thru space...perhaps chances of this are higher when galaxies merge--like when andromeda merges with the milky way. Maybe we are one of the first "cycles"' and when another planet long down the road turns on their receivers they will detect way more than cosmic radiation by default!! Our signal is less than a century old ...and even if we become extinct the information in that signal will continue...for us to now assume with confidence that life must exist (even radio intelligent life) then those signals like our own are indeed sending information thru space, right now--were just too early :/

Even Ray Kurzweil got in on the modified Drake equation. This was before we knew just how common exoplanets are, but he arrived at an estimate of one intelligent species in our galaxy - and here we are.

I hope you're pessimistic about how long we last. Do bear in mind that if humanity does migrate out from the Earth or "evolve into something different", it's highly likely we'll still be some sort of intelligent being.

Even so, I completely agree with your assessment that even in the most optimistic case, it's unlikely we'd be able to detect other intelligent life. They'd have to have been around long enough for their signals to reach us, and their signals would have to be extremely strong or extremely well-collimated for us to detect them. It's often pointed out that we can only be "heard" by anyone else within less than 100 light-years. Even if someone is that close (unlikely), how massive a receiver would they need to hear our early AM radio?

I'm sure there's life elsewhere in the universe. I find it likely that there's life elsewhere in the galaxy, but am entirely uncertain about intelligent life. But I'm pretty sure there isn't a massive, advanced civilization close enough to fly here on vacation.

The "where is everyone" question pretty much presumes that there are no "aliens" here. But maybe we're looking for the *wrong kind* of alien. One assumes that an intelligent spacefaring culture would be fairly well advanced with respect to nanotechnology. Maybe our alien friends just load up their probes with an informational payload, spray their probes all over the universe, and then wait for their little nano-proxies them to settle and begin replicating, using the local substrate.

Which is why we should be trying to communicate with prions.

There's one thing that these kinds of things always, always forget.

It is a pure accident that we are here. Dinosaurs owned this planet for 160 million years and did not evolve intelligence to the point of even basic tool use (that we are aware of). Sure, some species of bird do use tools, but that invention has come after another 65 million years.

There could easily be the optimistic number of planets that are teeming with life and the pessimistic number of planets with intelligent life (or even just one).

Evolutionary principles do not encourage intelligence.

Great write up!

My thoughts:

1. I know we are the not the only intelligent life for one reason: Identical sightings by similar but distinct reliable, qualified, and reluctant witnesses around the same time frame and location. (UFO Files: Black Box Secrets).

2. We are probably not alone relatively. If one has only one data point, then the odds are that our data point is near the bell of highest occurrence meaning we are less likely to be unique just due to raw odds.

3. Superior intelligent life may avoid detection intentionally. The "Prime Directive" in Star Trek is what I mean. Non-interference. For any life to achieve interstellar capability, their societal structures must be advanced. Advancement can only come from a developed societal respect for others, science, the natural world, etc. This respect would extend to us. This facilitates study of the naturally emerging advanced civilizations (humans). Also, humans tend to act hysterically and the knowledge that we could be dominated at any moment by an alien civilization would be incredibly destabilizing. While key world leaders may know, they would not divulge such info unless absolutely necessary or when the timing is right.

Again, great post! Fun stuff!

I want to clarify that in my point 1., that these were not just sightings but extended and close encounters. One lasted over 40 minutes.

Could you please provide a justification for the probability assumptions you are using here? Even the "conservative" estimates presented here seem irrationally exuberant.....

In his book "Signature of the Cell", Stephen Meyer presents the (almost) current state of origin of life research. He shows that there have not been sufficient probabilistic resources in the entire universe for the abiotic/prebiotic evolution of even a single modest length polypeptide (150 amino acids) that has any biological function to occur by chance.

The problem of specified information (genetic code) arising spontaneously is so great, that no attempts so far (Protein first hypothesis, DNA first hypothesis, RNA world hypothesis) have been able to account for it.

Folks seem to be ignoring an important part of Fermiâs Paradox: if it is possible, even at sub-light speeds, it should be cake to colonize the entire galaxy in the matter of a few million years. Since itâs *extremely* unlikely that different sentients races would evolve (and colonize) concurrently, looking out into the night sky *should* be like looking at Manhattan Island (itâs either wild or paved over). What we see now is natural wilderness.

The consequence of *not* colonizing the galaxy is dying with your native star.

That could have happened any number of times, simply because abiogenesis happened, but it never got smart enough, and therefore died. Thatâs what humanity will face if it fails.

The late Stanislaw Lem often adressed the problem of "Silentium Universii", the silent universe. He was pessimistic about any meaningful contact between any two civilisations because of the difference in technological level and the complete lack of common ground, apart from possibly the biomolecules in the bodies.

I would recommend Lem's "His Master's Voice" which I find a better novel than "Contact".

In the unlikely case a supercivilisation feels the need to spread through space they may prefer the cold "orphan" planets where ambient temperatures permit superconductivity -see the short story by Arthur C. Clarke from the early sixties. Due to gravity microlensing we now know that orphan planets probably are as common as planets still circling stars.

But I am not really hopeful that the aliens are hiding in the interstellar darkness -the null hyphotesis is that we are truly alone.

Sorry bro. We shouldn't be looking; we should hide!

Any civilization advanced enough to get in touch with us is either 50-100 years back technology wise or any state forward. How much time? How few civilizations? The odds that the nearest intelligent (communicable) species are thousands or hundreds of thousands of years in advance of us technology wise are good.

We should hide.

Fabulous article. But there seems to be a mistake here (see below). You mention 25,000 civilizations in the universe, when I think you meant in the galaxy:

"Taking the million-year estimate and our prior optimistic figure, that means there may be as many as 25,000 civilizations ready to communicate with us right now in the Universe."

"And if the optimists are right, there's still almost nobody out there for us to talk to! 25,000 civilizations in our galaxy, right now, still means that the nearest one is probably hundreds of (if not closer to one or two thousand) light-years away."

@Andrew #26

- Signature in the Cell is NOT the current state of abiogenesis research. Meyer knowingly mistates information and ignores much of the relevant literature on the subject. Many of the things he claims are not correct based on research done well before the book was published.

I would suggest several other books. The one that comes immediately to mind is Genesis by Robert Hazen.

@mhdann #29

- It's worse than that. Any life that started from stars of roughly the same generation should be about 50 million years ahead of us, technologically speaking. Remember the dinosaurs? We're an accident caused by a asteroid strike that wiped out the dominant life forms of the planet.

I have to agree with The Other Doug. If there are other civilizations out there, then they are fairly sparse and probably rarely leave their solar system. If they do, then, once we leave our solar system, we should find our galaxy littered with the remains of other civilizations.

Great article. Interesting set of statistics.

I'm not a religious person but the math all depends on one assumption.

"First, we need to make life from non-life"

Has this been shown to be possible?

@Tom K #29:

If you accept the premise that the origin of the universe happened roughly as depicted elsewhere on this blog, then you're aware that the very early universe was too hot even for atoms, much less the complex molecules we recognize as life.

So, when the universe began there were no chemical constructs we'd call life; today there are. Regardless of what happened in between or what caused it, life came into existence where previously there was only non-life. As far as I know humans haven't repeated that process in the lab, but it clearly happened at least once.

If you don't accept the premise that the early universe was devoid of life (or at least the carbon-based life forms we know and love), then I think you're on the wrong blog, as 2/3 of the posts here discuss the evidence for expansion and the Big Bang. ;)

If more advanced beings are out there, we'd better hope they don't find us. Experience on this planet suggests that when more advanced civilizations encounter less advanced ones, carnage ensues ....

Much too much is made of the so-called "Drake Equation." Why? Because it is a highly biased formulation. Every variable in it is intended to bolster an a priori assumption that life, statistically - MUST have arisen elsewhere. But Drake (intentionally, probably) left out at least one huge factor that points in the opposite direction.

Everything we know about the process of evolution says that it all started with one, single, event. That is to say that only once in the history of our planet did some molecule or collection of molecules stumble upon the "miracle" of self-replication; everything else evolved from that one-time, evidently unique event. While it is conceivable that the power of self-replication is so basic that it may have arisen many times, the evidence strongly suggests that only once in 4 1/2 billion years did it result in organisms that could evolve; otherwise DNA would likely not underlie ALL life. The evidence all but proves that every living thing on earth is related - can trace its beginning back to this one, incredibly serendipitous, event. If there was a God, this is all he/she/it did.

Drake's famous equation, had it been honest, should have included the enormous and virtually inconceivable number of opportunities for life on earth to have arisen without it ever happening, except once that we know of.

Admittedly, the immense number of stars, galaxies, and habitable worlds that may exist in the universe lends statistical heft to any claims of the likelihood that our wonderful selves popped up in many places and cast into the cosmic oblivion radio waves, fortuitously on our wavelengths, and at our geologically eye blink moment in time. It might even suggest that it happened thousands of times; and radio waves are criss-crossing all over the skies as we speak, while somehow missing out detectors for six decades.

But were it not disingenuous, Frank Drake's felicitous equation also should have included the approximate number of times molecules collided on Earth with nothing, so far as we can tell, happening. Furthermore, even after the evolutionary process began and life flourished, it produced many millions, perhaps billions of kinds living things while producing US (or any OTHER specific organism) only once. It seems to me that if life inevitably led to sentient beings, especially intelligent beings capable of far reaching communications technology in many locales throughout the cosmic expanse, it surely would have produced them more than once here on our home planet. But everything we know about life tells us that it not only happened once, but COULD only happen once.

The fact is that Drake and his anthropically hopeful colleagues were intent, not on finding truth, but on finding other special creatures like us somewhere in the cosmos. In this sense, some scientists can be said to have "faith" - to be essentially RELIGIOUS!

For the last 60 years or so, quasi-astronomers have been searching the skies for that yearned-for connection with alien worlds. Thus far they have found nothing (flying saucers notwithstanding); and I doubt very much if they, their children, or their grandchildren ever will. It's as likely, in my estimation, as finding God. I, for one, believe neither in any of the gods of theistic construction, nor in this one of quasi-scientific concoction.

First interstellar civilisation becomes galaxy-spanning long before the second one can even talk.

It's ridiculous odds for two or more to hit the same tech-point at the same time, so the first one to crack interstellar travel claims it all. And that's probably not us.

This isn't our galaxy, we just live in it.

1)Detect livable planets. Done!

2a)Detect evidence of non-earth life. (e.g. Mars or meteors) not Done.

----OR----

2b) Demonstrate abiogensis. not Done.

3) Detect technically advanced intelligent life. (e.g. SETI) not Done.

Will ET be found before or after the Higgs? or not not?

Why not us? I think we're in the best spot possible -- our sun is only a 3rd generation star, and although the universe will likely extend to infinity, entropy is increasing. The galaxy will slowly fill-up with white and brown dwarves, black holes, rouge planets and other chemically stable objects unlikely to create new, let alone intelligent, life.

We may be the only chance our universe gets.

I mean eternity, not infinity (i.e. time, not space.)

ANOTHER possibility: visualize a diver along the reef who looks down at the shellfish below. He passes them up without thought about communicating. An integalatic traveler would probably do the same as he zipped by our planet.

Why? A diver might ignore shellfish because...there's nothing unique about them. The same cannot be said for Earth or humanity. Now, maybe the traveler is simply uninterested in us -- fair enough, we need not speculate over xenopsychology.

However, it cannot be said that humanity or the Earth itself is somehow camouflaged. Unlike every dead planet in the galaxy, the Earth is immediately identifiable as a living planet, the oceans, land and even the sky terraformed by its inhabitants.

"Where is everybody?" Why then the somewhat contradictory complaints about UFOs, "they can't be that because it's too hard to get here." I realize, radio communication is easier than interstellar flight, but would you expect anyone to just "on their hands" century after century and not even try? Also, I realize that alleged UFO conduct and inconsistency is a problem, however it is still grating to see complaints from opposite sides of a scientific establishment.

Two comments and at least one of them has already been made:

1) you seem to be focusing on what could be called the weak version of the Fermi Paradox rather than the problem that Fermi himself was interested in. Which was, why don't we see signs of intelligent ETs here, NOW? We can call this the "strong" version of the Fermi Paradox. Sagan and others showed that the colonization time for the MW is very short, compared to the Hubble time. Given recent work published in the Journal of Astrobiology (sorry, forget the reference), the time period between the "arrival" of technological civilizations could easily be millions of years, which makes this even a worse problem.

While interstellar travel is certainly hard, it's by no means impossible, and at least a few civilizations ought to go "crazy Eddy" and try it, regardless of the costs.

2) I think you take a very, very optimistic view of the recent Kepler results. The best estimate of the number of terrestrial sized planets (not masses, yet, but that's a pretty good proxy) I've seen is that about 2% of F-M stars have "earth" sized planets in their habitable zones (the so-called "eta-earth" parameter). This is unlikely to change by as much as a factor of two (even including habitable moons), as Kepler has already extremely well surveyed the most numerous such systems, the late K and M stars (where the orbital periods are well covered by existing Kepler data). This drops the number of stars with "earth-like" planets in the galaxy down to just 1 or 2 billion, at most. From there, it's pretty easy to get N = 1. Of course, this doesn't address problem 1) above......

"When you think of all the social and political problems that we've solved (and are solving now) just over the past few hundred years, and the hurdles we have coming up over the next few hundred (including population, pollution, energy, resource management, human rights, and more), any civilization that talks to us has likely already solved those problems."

True but what if they're psychos?

True but what if they're psychos?

Then we'll have something in common already!

That is an awesome view into what it takes for life to exist on other planets. This just makes you think that if there is life how would it ever come and talk to us. Even more so, with your calendar, how do we even know that we are on the right date for them to contact us? Maybe they were able to communicate around December 24th of your calendar, but not now. That does us no good. You have my head spinning.

Where is everybody? They lived. They used up all their local energy and valuable materials. They died. Just like we will.

Well, I came in late on this one. Maybe know one will ever read this, but I think you guys are demonstrating a huge lack of imagination here.

I think that the answer to this question lies with Ray Kurzweil's predictions for the future of human technology. Based upon objective trends in computing, biological, medical, and nano technology, in less than 100 years humans will begin to transfer our conscious selves to machines. As machine life, we will become more intelligent, faster, and capable by large factors. This is the logical direction and conclusion of all biology based technical civilizations that have appeared in the universe.

However, the amount of time from the first radio broadcast, to emergence into the galaxy as fully formed gods (for lack of better term) is brief. Beings who have already transcended would have no more interest in dialogue with us, in our present state, than men would have in dialogue with a caterpillar.

It is possible that we may be monitored by other civilizations, but more out of scientific curiosity than parental concern. For them, we either make it, or we don't. Or, they may be completely unaware of our pending emergence. The Universe is large and the amount of time from initial broadcast to transcendence may be too brief for them to have become aware of us.

Either way, we won't find out until we "transcend" ourselves and go looking for the transcended descendents of our biological cousins out there.

One should also consider the possibility that intelligent life may abound in the universe, but may have advanced to the point where radio communication is totally obsolete, or was never implemented as better or different ways of communication were utilized first. Perhaps our modes of communication may be viewed as we view smoke signals. Another possibility is, given our violent nature, they simply do not wish to communicate with us and are blocking their signals. Intelligent life may have existed for eons, and we are the backwards children that they have no wish to condescend to.

Yes, we looked out into space for an exact replica of what we perceive ourselves to be, and found none. Job done. Skeptics, take it from here.

Wow, such science, such method!

While I do hold evolution as true, I do not buy the assumption that we are a grand accident. Too outlandish a claim. And despite the best attempts to brainwash me into skipping over pondering the issue, evolution is too successful to be explained by the current model. Not creator driven, mind you, just too successful for me to swallow the furtive religion behind some people in evolution. I do not buy the assumption that we have not and are not being visited. Again, a baseless and outlandish claim.

The odds are, that we are not alone, and are not un-noticed either. If you cannot fathom that, you need to stop claiming to be doing science, because you are not.

Abiogenesis in NOT a young field, it is a non-existent field. It is conjecture. It may be correct in the end, but right now it is simply conjecture and wishful thinking on many peoples' part.

If we continue to only look for evidence of ONE way of seeing the universe and its life, we will continue to be Fermented in Paradox.

Our whole universe was in a hot dense state,

Then nearly fourteen billion years ago expansion started. Wait...

The Earth began to cool,

The autotrophs began to drool,

Neanderthals developed tools,

We built a wall (we built the pyramids),

Math, science, history, unraveling the mysteries,

That all started with the big bang!

"Since the dawn of man" is really not that long,

As every galaxy was formed in less time than it takes to sing this song.

A fraction of a second and the elements were made.

The bipeds stood up straight,

The dinosaurs all met their fate,

They tried to leap but they were late

And they all died (they froze their asses off)

The oceans and Pangea

See ya wouldn't wanna be ya

Set in motion by the same big bang!

It all started with the big BANG!

It's expanding ever outward but one day

It will pause and start to go the other way,

Collapsing ever inward, we won't be here, it won't be heard

Our best and brightest figure that it'll make an even bigger bang!

Australopithecus would really have been sick of us

Debating how we're here, they're catching deer (we're catching viruses)

Religion or astronomy (Descartes or Deuteronomy)

It all started with the big bang!

Music and mythology, Einstein and astrology

It all started with the big bang!

It all started with the big BANG!

"While I do hold evolution as true, I do not buy the assumption that we are a grand accident. Too outlandish a claim"

Why is that outlandish?

And why is that more outlandish than the idea we have been created by design?

Was that designer just a grand accident? Or were they designed too? If designed, what about their designer?

But even if you want to keep that, what PRECISELY is outlandish about it?

The creation of each snowflake is a grand accident. Unless you posit some Jack Frost going around designing them all.

And it's not as if we're particularly well "designed" is it. Blind spot (Octopi have no blind spot because the blood vessels in the eye go *behind* the retina). Sickle cell anemea or Malaria choice. Choking hazard because our adams apple is high up the throat. And so on.

If we were designed, the designer was a moron.

"Not creator driven, mind you, just too successful for me to swallow the furtive religion behind some people in evolution."

Yeah the faithiests usually try to paint everything as a faith.

If you want to use that word, don't use it in a connotation of organised religion because the only accurate way of using it here is the same "faith" you have in that you will be protected by your seat belt in your car when driving.

How could you call it successful anyway?

Mass extinctions abound. The dead ends (similidonts and prey continue to pursue the same doomed cycle time and time again) the doomed specialisations (pandas).

Is this purely because you want to be actually something special, unique and the entire point of the exercise of creating a universe?

Because that's rubbish. You are creating a faith just like the faithiests so that you can feel special.

"I do not buy the assumption that we have not and are not being visited. Again, a baseless and outlandish claim."

Why do they hide after travelling thousands of light years?

That is an outlandish claim.

"The odds are, that we are not alone"

First reasonable claim you've made. Pity you couldn't keep the run going.

It's pretty easy telling the world they have it wrong.

Okay, NOT gonna read the rest of the comments, since I see it's devolved into an atheist/faitheist/theist discussion, and while I'm normally up for that fight (disclosure: I'm on the hardcore atheist end -- grow up, people, there's no sky daddy) I wanted to talk about the actual post instead. SO! That out of the way...

Great post! I had intuitively come to a similar conclusion without doing the formal analysis: That MAYBE there is intelligent life in our galaxy, but I wouldn't be on it either way... but there's no way we are the only intelligent life to ever have existed in the universe. One thing that I found interesting was that your rigorous pessimistic estimate meant that, while we might not be the only intelligent life ever in the observable universe, we might be the only intelligent life right now. Intuitively that seems rather dubious to me, but you went through the math, and there was never a point where I said, "That's so pessimistic it's absurd" (I do think some of the pessimistic estimates were pushing what is realistic, i.e. what I mea is you did a great job of hitting the extreme pessimistic end of the spectrum of plausibility -- I just don't think that's likely)

I sometimes like to take the optimistic estimates and fantasize about a thriving galactic culture near the center of the galaxy, where stars are so much closer together that contact or even limited travel might actually be feasible... but then somebody told me about all the ionizing radiation near the galactic core, and how that sorta puts a kibosh on the idea of life-as-anything-like-we-know-it. Spoil sports!

Well, James, since you've raised the dead here just to complain about what other people post, I guess you believe in life after death, hmm?

You know, instead of complaining about what other people say, why not just say what you want?

PS http://scienceblogs.com/startswithabang/2013/03/29/where-is-everybody-p… will send you to a thread that ISN'T going to be necro'd.