"This nebula had such a resemblance to a comet in its form and brightness that I endeavored to find others, so that astronomers would not confuse these same nebulae with comets just beginning to shine." -Charles Messier

Let's take a journey back in time to when our known Universe was a lot smaller. The only planets discovered were Mercury through Saturn: the naked eye planets. The well-known objects were our Moon, the (naked-eye) planets and their moons, and the stars and the Sun. After those, the only new objects that were routinely hunted in the night sky were those two-tailed recurring wonders: the comets!

Image credit: Loyd Overcash of DeerRidge Observatory, http://www.skyshooter.net/Comets.htm.

Other objects were known, such as novae and supernovae, but comet discovery was the primary goal of most astronomers of the day. In 1758, Charles Messier was no different, as he was eagerly anticipating the return of Halley's Comet, predicted by Halley himself to return in that year.

So you can imagine Messier's excitement when he looked through his large (for the time) telescope, and saw -- on September 12th of that year -- something much like this.

Image credit: Chris Brankin's Deepsky (Messier) Objects, from http://www.stargazing.net/.

The bright star itself isn't interesting, but that nebulous blob above and to the left of it sure looked like the early stages of a brightening, returning comet to Messier! But, alas, this was no comet, as it neither brightened nor changed position nor altered in appearance over the subsequent nights.

Messier quickly realized that he was looking not at a comet, but at a much more permanent nebula in the night sky -- a faint, extended object -- that could be easily confused with a comet by someone who didn't know about its existence. And so began the Messier Catalog, a list of (eventually) 110 objects that would frustrate unsuspecting comet-hunters.

Image(s) credit: SEDS -- http://messier.seds.org/.

But each object in the catalog, containing not a single comet, has a remarkable story in its own right. Each Monday -- starting today, the first "Messier Monday" -- I'll be highlighting one of these Messier objects, visible through small telescopes (or binoculars) under good conditions, for you. (And we won't be going in order, so if you've got a favorite, let me know!)

To begin, here's how you find Messier 1, also known as the Crab Nebula.

Image credit: generated by me, using Stellarium, downloadable at http://stellarium.org/.

Tonight, if you step outside, the great constellation Orion should rise shortly after sunset. Many degrees above the top two stars -- Betelgeuse and Bellatrix -- but not quite as far as the very bright Alnath (or the planet Jupiter), you'll find a modestly bright star known as ζ Tauri, a 3rd magnitude star visible even within most cities on a clear night.

And if you point a good pair of binocular at ζ Tauri (under dark skies), here's what you're likely to see.

Among the bright stars, ranging from a deep orange to a bright blue in color, you'll find an unmistakably distended, faint, and fuzzy object. That's the Crab Nebula, or Messier 1.

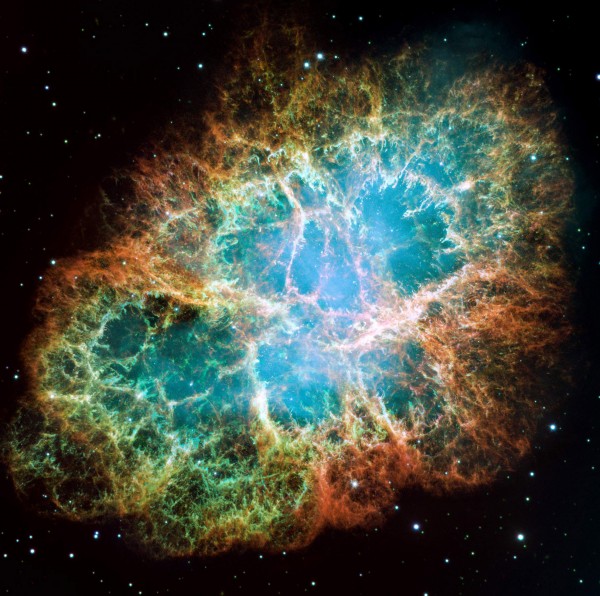

Even in the hands of an amateur with an excellent quality telescope-and-camera, the level of detail that can be teased out of this object is breathtaking.

What you're looking at is a star within our galaxy that died very recently: in 1054, to be precise! Since then, the supernova remnant has been expanding into the space surrounding it, creating the Messier object we know today as M1: the Crab Nebula.

And this spectacular object continues to evolve over time, as these two images -- from 1973 and 2000 -- demonstrate.

Image credit: © Adam Block / Mt. Lemmon Skycenter, combined with an older image from the Mayall 4m at Kitt Peak.

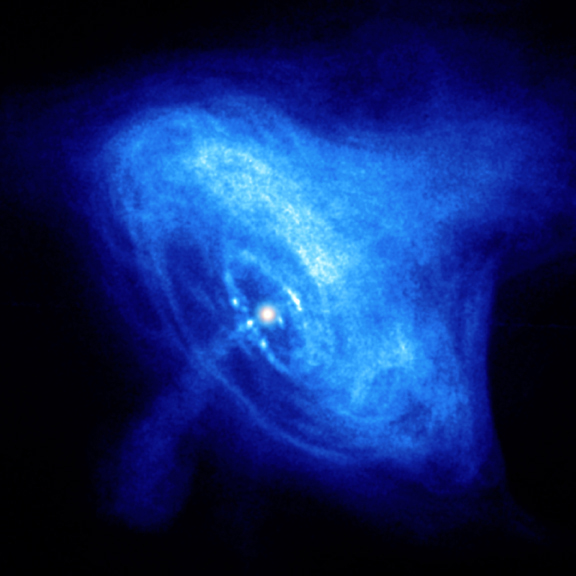

While the outer layers of this dead star continue to expand and cool, the inner core has collapsed into a pulsing, X-ray emitting neutron star, spectacularly visible to a space telescope like Chandra.

In fact, the pulsar -- spinning and pulsing some 30 times per second -- changes over time, as this seven-month timelapse video from the same Chandra team shows!

Although this image is an enhanced-color composite and mosaic (many images stitched together), the filamentary structure is real, as this detailed close-up illustrates.

This supernova remnant may yet trigger the formation of new stars as it continues to expand and interact with molecular clouds, while the inner neutron star will continue to change over time, as its environment is far from being in equilibrium.

Don't believe that last part? Take a look at the Hubble close-up of the inner region, taken just months apart back in the 1990s, of the space around the pulsar itself!

This object -- the very first Messier object -- continues to evolve over time, and will achieve its 1,000-year anniversary, as best as we can tell, in July of 2054.

Enjoy the very first Messier Monday; it won't be your last!

I like this idea. I'll keep coming back for it.

Great idea. Nice post. One info is missing though: how far is it from us. I think that next time you should specify the distance.

Very nice post. Excellent way to start a new chapter in SWAB. The Hubble image is impressive, but the zoomed in image of the filaments is breath taking.

Question for Ethan. Pretend you've won a prize. As the winner of the prize, super advanced aliens will pick you up after work and take you instantaniously to the celestial destination of your choice, granting you superman powers to fly around and not die until you were ready to go home. What would you want to do/see if you could only pick one thing/location. You are constrained by time (no going back to just before the big bang b/c something tells me you would)

Can you give us some idea of the dynamics that leads to the filaments and the larger structures?

Great post . Love your work here - cheers

Nice article about the Crab. But one sentence is either a typo or makes no sense.

"Even in the hands of an amateur with an excellent quality telescope-and-camera, the level of detail that can be teased out of this object is breathtaking."

I mean... if it said "even... WITHOUT excellent...." then I could understand.

But if you HAVE excellent quality telescope and camera then you're not so much an amateur anymore, and it's normal that you'll get great detail.. that's why you have excellent quality :)

So in that sentence am not sure what you wanted to say :)

p.s.

The thought to have a weakly astronomy class on Messier objects... AWESOME!! :)) So looking forward to it.

UPS... sorry about the typo above... should be "weekly". :(

“Even in the hands of an amateur"

I think it makes sense as written. I would venture to suggest that a significant percentage of "excellent quality telescopes" are not only owned by amateurs, but spend many years confined to their basements once the novelty has worn off. A good telescope reflects more on the disposable income of its owner than on his skill in using it.

Part of the problem IMO is that you can get a scope and tripod for much cheaper than they are separately, but you get one that is only as good as the scope you have bought.

That means when you start off you have a cheap-ish scope and therefore a mount that only just manages it (e.g. a Skywatcher EQ2 and a 130mm Newtonian).

Problem is that if you like it and upgrade, you can't use that mount any more. So you have to buy a new one. Better would have been to buy one much better (EQ5 for example) because the mount lasts many telescopes.

That then makes you want to go for a more expensive scope so that it lasts longer.

And either you have too much to learn at once and get overwhelmed, find out that you don't really have the time or location or even inclination for this, or get on with it well enough.

Two chances to fail to use what you bought.

And although an SCT is a common starter scope, it is rather hard to get used to (especially if it is a GOTO) and still quite expensive. And hard to shift.

*singing* Just Another Messier Monday.

I know this is the first. Don't worry; I'll be recycling that comedic gold next week.

I'm pretty sure Ethan meant "amateur" in the literal sense of "unpaid", not the negative connotation of lacking skill. Making proper use of the good equipment requires skill. But both the equipment and the know-how is increasingly available to amateur astronomers. It's awesome because astronomy is one of those fields where enthusiastic amateurs can still make significant contributions.

Of course it *does* require a fair bit of disposable income. So yes, one could say that's the first thing possession of such equipment tells you about a person.

Personally I think the biggest problem is people trying to get into astronomy on their own, without a group, pretty much necessitating a GOTO scope to get any enjoyment out of it (for most people) and thus preventing the learning of important telescope-using skills. Fortunately I wasn't in that boat.

What you’re looking at is a star within our galaxy that died very recently: In 1054, to be precise!

Lucky for life on Earth it died several thousand years before it could be observed from our solar system in 1054. Oddly enough, the wiki link doesn’t appear to give the the actual date/distance.

We know the date on which it we first observed its death (which could be called 'when it happened' from our perspective, given special relativity and all) with far greater precision than we know it's distance. The wiki link does give the distance, and it's 6.5k +/- 1.6k light years.

It's nice to keep in mind that looking at distance objects is also looking back in time, but let's not try to be needlessly pedantic about it.

In the photo showing the difference between 1973 and 2000, I see some "stars" appear or disappear. Are these alien vessels, perhaps on their way here to demand Woody Woodpecker VHS tapes? I'm assuming yes, because I don't see any other explanation offered in this paragraph.

Donovan - re the first part of your comment

There is a difference in exposure/sensitivty between the two images. I would guess that some stars were too dim to see on the lesser exposure and 'appeared' due to the greater sensitivty of the later image.

As to the latter comments I have no idea what you are trying to say. Perhaps you could elucidate.

Donovan, there is at least one star (near top, right hand edge) which can't be explained by Shane's hypothesis as it varies too much. As M1 was seen as a possible comet, I would think it is quite close to the ecliptic, and that "star" is actually a planet.

I recall reading that the total energy output of the pulsar is around 100.000 times the luminosity of the sun, but the optical component is of course scattered by the nebula. So if this was a point source you would have a star at the distance of 6500 ly that was visible to the naked eye. Not bad.

--- --- --- --- --- ---

There are some supernovas that were never observed that have left a "light echo" in the interstellar medium, visible at the edge of sensitivity of the best telescopes. They not only show the approximate position of past supernovas, they also light up previously dark nebulas.

The crab nebula supernova was visible during the daytime.

That's how bright it was.

I am visible during the daytime, but that doesnt mean I'm bright.

You reflect the brightness around you, though.

Out in space, there's nothing to hear you gleam...

(you derserved that...)

I can't image what is more beautiful than space.

thatz beautiful

I will disappoint many people with this information, but the starting point of creating mythology of Jesus Christ served as a supernova M1 (Crab Nebula), which occurred May 11, 1184

. This is an astronomical phenomenon is reflected in the myth of

Phaeton. This period of our history can be considered and the date of the split

then the dominant religion in the three main branches.

I understand a good number of 80s rock band members are bummed out because their music won't travel through space: there's nothing to make it glam.

thank you, thank you. don't forget to tip your waitress.

Well, it's kind of late now, but I've got another hypothesis to explain the difference in stars between the 1973 & 2000 images. It looks like vignetting to me. Notice that pretty much all the stars missing in the 1973 (purple) exposure are around the corners of the image. Thus, vignetting.

Another possibility would be variable stars, but I'd bet on camera/telescope limitations, i.e. the vignetting.