"I have just gone over my comet computations again, and it is humiliating to perceive how very little more I know than I did seven years ago when I first did this kind of work." -Maria Mitchell

Well, it's getting close to the end of October, the Moon is waning towards its new phase, and -- at least in the northern hemisphere -- the days are getting shorter and the nights are lengthening. Is there anything unique on its way that's worth watching the skies for? In today's Ask Ethan column, our suggestion comes from longtime reader and commenter Sinisa Lazarek, who inquires:

Since ISON comet is soon going to show up, maybe an article on that could be cool. What can we expect, what would be the best days for observation etc. Since my understanding is that it's gonna be really bright and big, maybe host a little photo contest or just for fun.

Hope you like the suggestion and keep up the excellent blog! We all love it!

You might have heard of this referred to as a potential "Comet of the Century," so let's start off with the comet of last century that many of you will remember: Hale-Bopp!

Hale-Bopp is a very large, periodic comet that came through the Solar System in 2215 B.C., when a very close encounter (a near collision, in fact) with Jupiter changed its orbit dramatically, as close gravitational encounters often do. With a nucleus around 30-60 km in diameter, it's much larger than most known comets; the famed Halley's Comet has a nucleus of only around 10 km for comparison.

And an important combination of factors: that Hale-Bopp is large, that it's thought to be a very young comet (making possibly only its second pass through the inner Solar System in the 1990s), and that it emitted a lot of (reflective) material as it passed near the Sun made for a spectacular show in the 20th Century.

Image credit: A. Dimai, (Col Druscie Obs.), AAC, via http://www.cortinastelle.it/.

Image credit: A. Dimai, (Col Druscie Obs.), AAC, via http://www.cortinastelle.it/.

Visible to the naked-eye for 18 consecutive months and outshining all but the brightest single star in the sky (Sirius), Hale-Bopp is believed to be the most viewed comet in all of human history. In the images above, you can see the blue (ion) tail and the white (dust) tail, something common to practically all comets.

But not all comets that pass through the inner solar system put on a show like Hale-Bopp did; back in the 1970s a potential "Comet of the Century," known as Comet Kohoutek, disappointed skywatchers across the globe.

Sure, it was visible to the naked eye, and yes, it became quite bright. It was not quite as large as Hale-Bopp, but it was also thought to be a very young comet (in terms of having made a very small number of passes through the inner Solar System), and it would also pass very close to the Sun (passing well inside the orbit of Mercury), something that Hale-Bopp did not do.

Passing close to the Sun is a mixed bag, mind you, when it comes to comets.

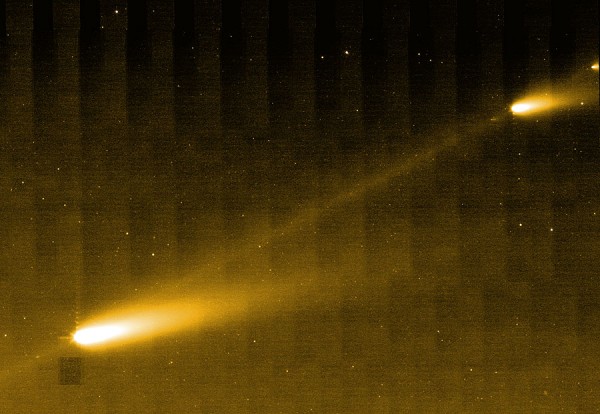

Image credit: Colin Legg, via Bob King of AstroBob; http://astrobob.areavoices.com/.

Image credit: Colin Legg, via Bob King of AstroBob; http://astrobob.areavoices.com/.

The rather unremarkable Comet Lovejoy passed very, very close to the Sun, so close that it's a special type known as a sungrazing comet. This is a double-edged sword; when comets pass very close to the Sun they can be evaporated completely, they can become fragmented and muted, or they can -- as Lovejoy did a few years ago -- offgas spectacularly, and create a fantastic display. The tough part about sungrazers is that while they become objectively very bright, they also reach their peak brightness when they're very close to the Sun, meaning that you might not be able to see them even if they are spectacular!

There's something else worth remembering about comets that differentiates them from things like the Moon and the stars: even if they're very bright, they're also extended objects, which means that brightness is spread out over a large area. And this matters.

Image credit: Takamasa Takahashi of St. Norbert College, via http://home.snc.edu/.

Image credit: Takamasa Takahashi of St. Norbert College, via http://home.snc.edu/.

On the left is the Big Dipper; on the right is the Andromeda galaxy. The middle star in the dipper -- Megrez -- connects the handle to the cup, and is the dimmest star of the seven. The Andromeda galaxy has the same brightness as Megrez, yet while you can easily see Megrez from within many heavily light-polluted cities, Andromeda is much more elusive, because its brightness is extended over a large area.

So it goes with a comet as well. Even if a comet reaches the same brightness as the full Moon, it won't be quite as dominant in the sky as the full Moon, as its brightness will be extended over a much larger area. Which brings us to Comet ISON.

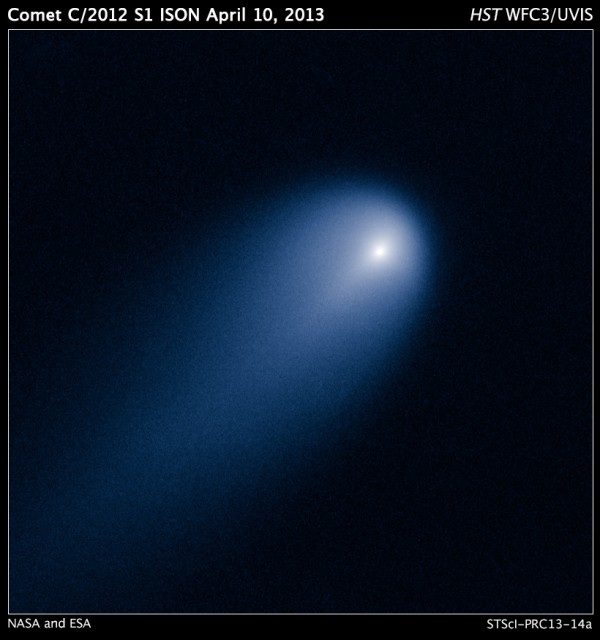

Image credit: NASA, ESA, J.-Y. Li (Planetary Science Institute), and the Hubble Comet ISON Imaging Science Team.

Image credit: NASA, ESA, J.-Y. Li (Planetary Science Institute), and the Hubble Comet ISON Imaging Science Team.

ISON was discovered by an international project that uses 30 telescopes across the globe to monitor the sky searching for comets: the International Scientific Optical Network. (That's why it's named comet ISON.) This was comet ISON as imaged by Hubble in April, when it was the same distance from the Sun as the planet Jupiter. As you can see, there was not yet a "dust tail" but only the blue ion tail, which is all that very distant comets get. The ultraviolet radiation from the Sun is enough to ionize carbon monoxide (and the CO+ ion produces that blue glow), but it isn't until the comet gets closer to the Sun that a significant dust tail appears.

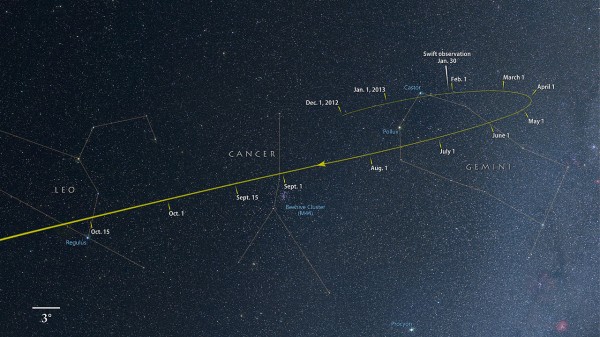

But over the past year, the comet has gotten much, much closer, and we've been able to follow its path through the sky.

By this point -- October -- it's a lot closer to the Sun, and there's a dust tail (in white) to go along with the characteristic ion tail. Hubble took a second look at it, and discovered something very interesting, at least from my point of view.

Its nucleus is completely intact! It's very difficult to gauge its size, but it's hard to believe based on what we've seen so far that we're looking at a Hale-Bopp-caliber comet. Astronomer Karl Battams has been very critical of the media circus calling this the "Comet of the Century," stating unequivocally:

Few serious astronomers and cometary scientists have ever felt ISON would be 'brighter than the full Moon'. ... That's entirely the media's term, and we've been saying this for months, that none of us in the [Comet ISON Observing Campaign] foresee ISON getting that bright, and never have done so.

You may have seen this lovely Adam Block picture of ISON, though, showing a green glow that Hubble missed.

This extended, green coma is due to carbon-carbon and carbon-nitrogen molecules being released as the outer layers of the comet sublimate. But the still-intact nucleus makes this a potentially very interesting comet, because it could brighten tremendously when it reaches perihelion, or the closest approach to the Sun.

And believe it or not, perihelion is coming up really soon, and the comet is going to be really close to the Sun!

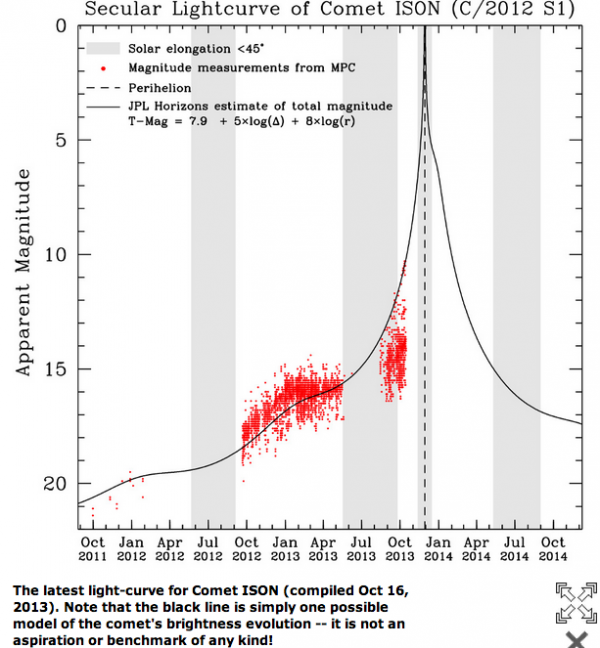

Image credit: compiled October 16, 2013 by Matthew Knight, via http://www.isoncampaign.org/.

Image credit: compiled October 16, 2013 by Matthew Knight, via http://www.isoncampaign.org/.

But if it survives its close encounter with the Sun and brightens as expected, it should be around as exciting as Comet Lovejoy was, with a reasonable possibility to match Comet McNaught, the comet-of-the-21st-century-so-far.

Image credit: fir0002 | http://flagstaffotos.com.au/.

Image credit: fir0002 | http://flagstaffotos.com.au/.

What will happen after perihelion?

Will it produce a spectacular show for all earthly observers? Will it leave a trail of Earth-crossing dust and create a new meteor shower: the ISONids?

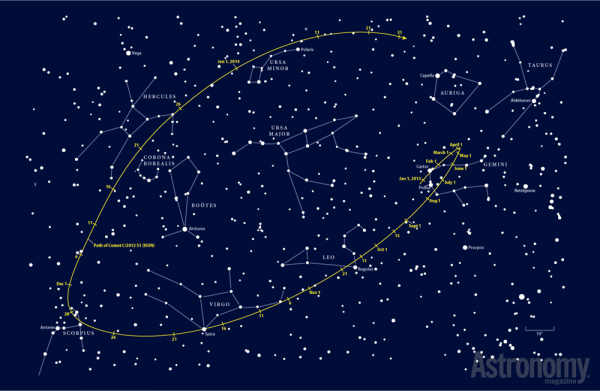

Assuming it survives, it will get closer-and-closer to Earth once it passes perihelion until the day after Christmas, where it reaches its nearest point to our planet. And if you want to know where to look in the sky for it, Astronomy Magazine has created an extremely helpful chart.

You can track comet ISON in real-time, and if you want to take photos, sure, you could send them to me, but you'd be a lot smarter to send them to the National Science Foundation, where your photo could win you thousands of dollars!

Image credit: screenshot from http://www.astronomy.com/ISONphotos.

Image credit: screenshot from http://www.astronomy.com/ISONphotos.

Unfortunately, that's what we know to the best of our abilities so far about comet ISON. I'd like to be able to tell you more (as would many others), but the truth is we don't know enough about ISON's nucleus, origins or structure to predict more than I've told you.

Regardless of how you feel about our uncertainties, it has a chance to be a spectacular show for skygazers, so I hope you'll follow its progress! And if you have a question or suggestion for me, drop me a line!

- Log in to post comments

One thing you (& Astronomy Magazine, at least) left out was whether this one will be an evening or morning comet. Based on the sky chart & where I roughly guess the Sun should be then, it looks like morning to me (also like Hale-Bopp & McNaught, as I fondly recall). Is that right?

Randy,

It will be a morning comet until about mid-November, when it will become completely invisible as it passes too close to the Sun, then an early evening comet on the latter side of perihelion.

It will also, during December 2013 and into 2014, head nearly due north, and will nearly pass by Polaris. If it remains naked-eye visible for a couple of months, you should be able to see it (from the northern hemisphere) through the majority of the night.

Hi Ethan,

thank you very much for covering my ISON questions :) Much appreciated. Hopefully it survives it's date with Sun and we enjoy some winter lightshows :)

no chance of it colliding with the earth and reanimating the dinosaurs I suppose?

No, ISON will remain a morning comet after perihelion and through its (likely) best viewing interval, i.e. the first week of December - see the maps in my ISON book, online and open-access at http://kometison.de under "FAHRPLAN"). Only in case the comet generals a very long tail, the latter may also become visible in the evening sky. With ISON heading straight north in the following December weeks the evening viewing conditions improve but don't become really good before the comet has faded away.

I stand corrected; although ISON ought to be visible beginning on about Dec. 4-6th after sunset for a brief while, there's a much longer window (about an hour) before sunrise to catch it. In addition, you can begin spotting it about a week earlier in the morning skies than you can in the evening skies.

Thanks, Daniel.

@Randy: I'm surprised you think of Hale-Bopp as a morning comet. It seemed to hang forever in my nighttime sky. Two tails naked-eye visible from the middle of a light-polluted city. What a beauty.

McNaught was a fantastic evening comet for me. It was really very impressive, becoming visible just as the Sun set.

ISON survived the Sun encounter. At least something survived. Weather a cloud or actual fragment is uncertain. Just wish I had clear skies and not clouds and snow :(

RIP ISON. You came, you shown, you met our Sun, you got vaporized...