“It’s a brilliant surface in that sunlight. The horizon seems quite close to you because the curvature is so much more pronounced than here on earth. It’s an interesting place to be. I recommend it.” -Neil Armstrong

Whether it's a job, a college/University, a scholarship or a competitive program, we've all had occasions where we've had to go through the application process in one form or another. And in almost all cases, that means we've needed to get recommendations from others.

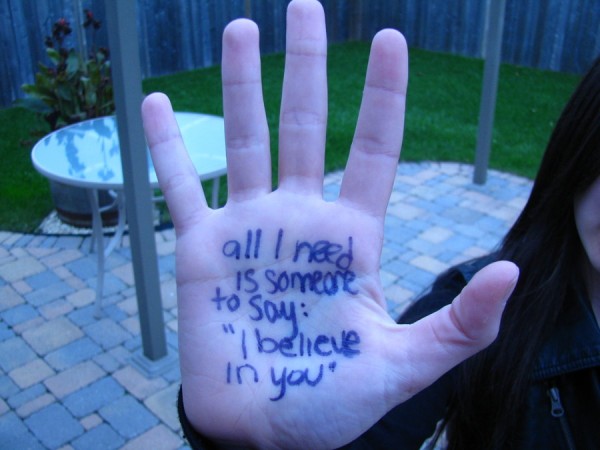

Image credit: Linkedsoul of deviantART, via http://linkedsoul.deviantart.com/art/All-i-need-is-someone-to-say-i-bel….

Image credit: Linkedsoul of deviantART, via http://linkedsoul.deviantart.com/art/All-i-need-is-someone-to-say-i-bel….

But what makes a good recommendation? And how do you know who you should be asking, who you should turn down, and who -- if you're on the other side of the desk -- you should (and shouldn't) be writing them for?

Image credit: Ariel Elliott of http://oh-hello-life.blogspot.com/2014/03/career-or-careers-crossing-th….

Image credit: Ariel Elliott of http://oh-hello-life.blogspot.com/2014/03/career-or-careers-crossing-th….

Some answers, some important points to consider, and some personal stories all for your consideration presented in full here.

- Log in to post comments

This seems like a very serious misunderstanding of your role as a scientist:

"Here’s the thing: if someone asks you for a letter of recommendation, and you wouldn't say extremely, overwhelmingly positive things about them, you shouldn't write them a letter. I won’t do it; I won’t write anyone a letter of recommendation that damns them with faint praise. If you have to think twice about recommending someone, whether that means you can’t remember them or whether that means there were five-to-ten other people in that class you’d recommend above them, you shouldn’t write a recommendation for them."

Wait, what? So if a student who you know to have low scientific integrity - say, there were problems with low-level plagiarism of others' work in the past? - asks for a letter of recommendation to graduate school, your opinion is that you should say no?

If everyone acts this way (categorical imperative!) how does the graduate school ever find out that this applicant has low scientific integrity? Isn't that a fact YOU would want to know before you accepted this person into grad school? (Over some other, more ethical candidate?) Why do you feel as if you have zero obligation to tell the graduate school about this fact?

To take a less extreme example: a perfectly average student is applying for a highly competitive job. The people who are hiring for that job shouldn't know that you regard that student as average (after you explain what average means among your students)? Why not? Isn't that information YOU would want before you hired that person?

The only reason you give for this [totally baffling] position is about how someone might get "shut out of [their] dreams" - as if someone's [possibly deluded] personal dreams of becoming a doctor is automatically more important to the world than whether they'll be a *good* and *ethical* doctor - or whether one of a finite number of medical school spots should go to this person rather than someone else who might do better in it? The hurt feelings of the applicant are not nothing, but I don't think the ethical calculation is straightforward: and here you have failed to consider the public good entirely.

Not everyone gets - or even deserves - to have their dreams fulfilled. If your dream is to be a doctor, and you've been lazy throughout undergrad, or you'd make a terrible doctor - you don't *deserve* to become a doctor. And your feelings notwithstanding, it could well be better for the world if you don't.

So precisely what is your obligation to the larger community, scientific and otherwise, in writing letters of recommendation - and how do you balance that against your obligations to a student or trainee asking you for a letter? That's your next blog post.

AP @1: Are you prepared to defend such comments in a court of law?

Here in the US, the law presumes that the student has the right to see relevant educational records, including letters of recommendation. Most departments, at least in my experience, ask applicants to sign a waiver specifically giving up the right to see their recommendation letters. But I don't know if that's true for all departments, and I last applied to grad school mumblety-mumble years ago, so things may have changed since then. Other countries have different laws. I have heard anecdotally that in the business world references are only expected to verify dates of employment, because they fear being a defendant in exactly this kind of lawsuit (the privacy laws that apply to universities do not apply to other employers generally).

More importantly, is it fair to the student if you allow him to waste his time in a futile attempt to get in to grad school? Better to be up front about your reasons why you cannot write an enthusiastic recommendation. Maybe it was an isolated incident and the student has mended his ways. Maybe it was more widespread, in which case the student should be getting pushback from other professors as well (I realize this does not always happen in practice). Or maybe your interpretation of what happened is incorrect, and it's definitely not fair if your error is what prevents him from getting in.

Eric, the legal points raised in paragraph 1/2 are - while of potential practical importance - totally orthogonal to the ethical questions I asked.

You ask, "Is it fair to the student if you allow him to waste his time...?" Maybe. Is it fair to the graduate school if you allow them to waste their time by withholding vital information from them? Again, I don't think there's an easy answer here: you seem to think there is.

I will repeat what I said above: "The hurt feelings of the applicant are not nothing, but I don’t think the ethical calculation is straightforward: and here you have failed to consider the public good entirely...So precisely what is your obligation to the larger community, scientific and otherwise, in writing letters of recommendation – and how do you balance that against your obligations to a student or trainee asking you for a letter?"

You've offered no guidance on how to balance your obligations to the larger community. You've not even acknowledged that you HAVE ethical obligations to the larger community. At present, however, you're suggesting that there are no obligations outside of the student, which difficult to credit (if the words "scientific community" mean something to you). So my questions for you are:

1. When considering letters of recommendation, do you have any ethical obligations to anyone other than your student? If so, to whom, and what are they?

2. If you don't have any obligations to anyone but your student, then there is no ethical issue with lying on a letter of recommendation. In fact, there may be an affirmative ethical duty to lie, if your only ethical obligation is to the student. Do you feel comfortable lying on a letter of recommendation?

3. If you do have obligations - among them, not to deceive - to others (say the scientific community), then consider that not writing a mediocre letter is quite plainly lying by omission. Do you feel comfortable lying by omission?

4. If like most people, you feel that point 2 is not okay, but point 3 is okay, then: why is lying by omission acceptable, by lying by commission unacceptable? Is that a real ethical distinction to make, or is that just a matter of personal comfort and cognitive bias?

[It's worth noting in passing that this is a near perfect parallel to failing to publish null findings from randomized controlled trials, in that it is lying by omission that hurts the scientific community and public as a whole, and ultimately and inevitably damages the credibility of the underlying enterprise.]

5. If you were considering this student for a job, would you prefer to review: only glowing letters of recommendation? Or: honest letters of recommendation, which did more than say only "extremely, overwhelmingly positive things about" the applicant, but honestly appraised their pros and cons, which allowed mention of fault? Which would be more useful to you?

If your argument is that the public good is served sufficiently by discouraging the student from applying - even if they wind up applying successfully in the end - then fine. Make that argument. I might agree - like I said, it's a complex ethical question, and I've never claimed to have an answer.