Expert Consensus on the Economics of Climate Change is a report from the Institute for Policy Integrity1, and comes to me via Slate via Twitter. I read the paper and failed to find the obvious flaws, so over to you.

Expert Consensus on the Economics of Climate Change is a report from the Institute for Policy Integrity1, and comes to me via Slate via Twitter. I read the paper and failed to find the obvious flaws, so over to you.

They ran a 15-question online survey... We invited the 1,103 experts who met our selection criteria [publication in journals] to participate, and we received 365 completed surveys. The survey data revealed several key findings [trimmed]:

• Economic experts believe that climate change will begin to have a net negative impact on the global economy very soon – the median estimate was “by 2025,” with 41% saying that climate change is already negatively affecting the economy.

• Respondents overwhelmingly support unilateral emissions reduction commitments by the United States, regardless of the actions other nations have taken (77% chose this option over alternatives such as committing only if multilateral agreements are reached).

• The vast majority (75%) of respondents believe that the most economically efficient way for states to comply with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s “Clean Power Plan” carbon regulations is through “market-based mechanisms coordinated at a regional or national level (such as a regional/national trading program or carbon tax).”

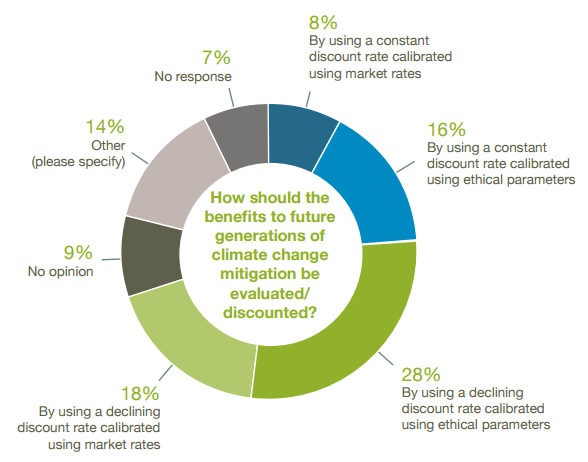

• ...a constant discount rate calibrated to market rates – was identified by experts as the least desirable approach for setting discount rates in the context of climate policies. Nearly half (46%) of respondents favored an approach that featured declining discount rates, while 44% favored using rates calibrated with ethical parameters.

• Experts believe that there is greater than a 20% likelihood that this same climate scenario would lead to a “catastrophic” economic impact (defined as a global GDP loss of 25% or more).

• Our findings revealed a strong consensus (69%) that the “social cost of carbon” should be greater than or equal to the figure currently used by the U.S. government (only 8% believe the value should be lower).

It is all interesting, so I recommend reading the report. Much of it was surprising to me; most obviously, 50% chose "Immediate and drastic action is necessary" as their response to "Which of the following best describes your views about climate change?" Perhaps this is a question-phrasing problem; but they also had "Some action should be taken now" available as a choice, which 43% picked, so I can't quite see how. 41% picked "Climate change is already having a negative effect on the global economy", 22% "by 2025", and 26% "by 2050". OTOH, figure 13, the median estimate for effect of +3oC on global output is small-negative. I was pleased to see that 75% went for "75% Market-based mechanisms coordinated at a regional or national level (such as a regional / national trading program or carbon tax)" as the most efficient mechanism; by contrast, performance standards got 13%.

On the vexed question of discount rates - which has come up before - they surprise me again by going for some wishy-washy ethical stuff or a declining rate. On the possibility of catastrophe, always a popular one, they take some care2 with their phrasing: “Some people are concerned about a low-probability, high-consequence outcome from climate change, potentially caused by environmental tipping points. Assume by ‘high-consequence’ we mean a 25% loss or more in global income indefinitely. (Global output dropped by approximately 25% during the Great Depression.) What is your median/50th percentile estimate of the probability of such a high-consequence outcome if global average temperature were to increase 3°C by 2090?” The median estimate looks to be essentially-zero, but the average is 10-20%.

As a last hurrah, they estimate from their responses an implied present-day social cost of carbon at a little under $100 per whatevs.

Notes

1. About which I know nothing. Wiki on Richard Revesz says After [Retaking Rationality: How Cost Benefit Analysis Can Better Protect the Environment and Our Health] was published in 2008, Revesz and Livermore co-founded the Institute for Policy Integrity, a NYU Law-affiliated advocacy organization and think-tank dedicated to improving the quality of governmental decision-making. Established in the last few months of George W. Bush's presidency, the institute quickly got in the news for spotlighting the Bush administration's rush to adopt a raft of controversial regulations, known as "midnight regulations".

2. Despite their care, they have not been sufficiently precise. Indeed, Timmy blows an enormous ambiguity in their words (see comment 2); so huge, that its hard to understand how they don't plug it.

Refs

- Log in to post comments

Interesting. I ran through the questions and unexpectedly found myself right in the middle of a pack of economists.

Economists: Hi, new guy! Come on over! We haven't seen you around before, what do you do?

Magma: Hey, everyone. Well, I'm a scientist, and...

Economists (a little more coolly): We're *all* scientists here.

Magma: Of course... the dismal science, right?

Economists (coldly): A smart guy like you probably remembers where the door is.

"Experts believe that there is greater than a 20% likelihood that this same climate scenario would lead to a “catastrophic” economic impact (defined as a global GDP loss of 25% or more)."

Well, sorta. There's two ways that statement can be read.

1) A 25% fall from current GDP.

2) At some future date either a fall in or a slower than otherwise expected rise in GDP from the level it is at at that future date.

Absolutely no economist believes in 1) and 2) is essentially Stern's limiting outcome at the bad end ("up to" 20%).

With the SRES predicting global GDP in 2100 at 5x to 11x 1990 global GDP, 2) isn't actually as scary as all that, tho' obviously best avoided.

[Ah yes that's a good point I should have noted -W]

Strange, Eli remembers many Tols wailing about how damaging that 5x was. Of course, Richard may not be an economist.

What is interesting whatsoever the word processing is, is that the wing was so heavily weighted.

It is all interesting, so I recommend reading the report. Much of it was surprising to me

That's because lately you seem to be getting all your ideas about economics from "Timmy".

OK, the previous comment was a bit harsh. Feel free to consign it to stoat-spam, or else leave it here with this follow-up as an apology, whichever you prefer.

[Thank you :-) -W]

Is the projected world GDP/population a curve to use?

[Do you mean, for projections of future CO2? I would assume so -W]

Wait. Above we have this:

-------------------

"Assume by ‘high-consequence’ we mean a 25% loss or more in global income indefinitely. (Global output dropped by approximately 25% during the Great Depression.)"

-------------------

followed by this:

-------------------

"1) A 25% fall from current GDP.....

Absolutely no economist believes in 1)..."

------------------

The "fall from current GDP" due to not "producing" the "Product" left unburned would be in that range, right?

Are the economists assuming some magical replacement Product will replace that?

[I'm not sure I understand your question. The question posed in the survey was on the likely effects of GW, assuming continued use of fossil fuels, and hence continued temperature rises. Had they been asked what the effects of ceasing all emissions immeadiately were, they would undoubtedly have predicted far more than 25% loss -W]

This seems akin to "anything but CO2" -- the notion something behind the curtain can explain both counteracting the warming physics says the greenhouse gases cause, and then causing a comparable warming to match observed reality.

Don't the economists say "anything but carbon" will fuel continued growth, and so they can't imagine removing carbon can cause that 25 percent loss in GDP?

[Again, I don't understand what you're saying here. The question, as asked, implies continued carbon emissions -W]

I mean, hell, so the economists can't imagine a 25 percent drop in GDP. Reality has already demonstrated it can happen.

[I don't understand that, either. The question itself reminds people that the drop during the great depression was around 25%, so no imagination is required -W]

“Economics was like psychology, a pseudoscience trying to hide that fact with intense theoretical hyperelaboration. And gross domestic product was one of those unfortunate measurement concepts, like inches or the British thermal unit, that ought to have been retired long before.”

― Kim Stanley Robinson, Blue Mars

Okay, I found a video demonstrating by analogy how economics works. Think of fossil fueled growth as analogous to gravity: pervasive, taken for granted....

http://i.imgur.com/EwxmVa1.gifv

[I think you're confusing economics with something else. "Economics is the social science that describes the factors that determine the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services" (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economics). You, and a great many others, are I think confusing it with a political programme desirous of growth without constraint -W]

I'm surprised that even 13% of economists would prefer performance standards. My guess is they're doing what law professors call "fighting the hypothetical" and decided you just can't get an adequate price for carbon as a political matter, but the medicine goes down better when sweetened as peformance standards.

On discount rates, I don't feel like I've got a good handle on them. I understand there's a good theoretical reason for saying very long term discount rates should be smaller than short term.

My intuitive sense is there should be one discount rate for future economic damages and another rate for future lives lost, but I don't think that's how it's done.

> the social science that describes

> the factors that determine ...

Ah, I have no problem with the purely descriptive economists.

Well, except finding them. Mondragon has some interesting ones, I've read.

It's the prescriptive ones that worry me -- those KSR describes as participants not in a dismal science but rather in a cheerful religion.

HR writes: "... I have no problem with the purely descriptive economists....It’s the prescriptive ones that worry me"

Many would argue this is exactly wrong. The preference for elegant equations has led many economists to mistake mathematical rigor for reality. Economics isn't physics. It's intimately tied to value judgements. Neglecting that leads to many 'optimizations' that most would consider nonsense.

Steve Waldman has a nice little example of this misuse of economic math:

"Suppose there were an economy that, in isolation, could produce 50 bottles of wine and 40 bolts of cloth. If the borders were opened, the country would specialize in wine-making. Devoting its full capacity to the task, it would produce enough wine so as to be able to keep 60 bottles for domestic use, even while trading for a full 50 bolts of cloth. Under the presumption that people prefer more to less, “the economy” would clearly be made better off by opening the borders. There would be more wine and more cloth “to go ’round”.

However, in practice, skilled cloth-makers would be impoverished by the change. They would be reemployed as menial grape-pickers, leading to a reduction of earnings so great that they’d have less cloth and less wine to consume, despite the increase in overall wealth. Opening the borders is not a Pareto improvement: the “pie” grows larger, but some people are made badly worse off. "

An entire generation (or two) of macro-economists was led astray by Lucas/Prescott/Fama and their mathematical beliefs in the efficient markets hypothesis, rational expectations, real business cycles, and that if it isn't micro-founded it either doesn't exist or can't be modeled.

A simple IS-LM graph has had more explanatory power of the *real* economy than all of the above's mathematically elegant equations. You won't find sticky prices or nominal wage rigidity in the economic models of these 'Chicago School' of economists. Yet any model that hopes to mirror reality better include them.

[Your example is the std mistake that people who don't like Ricardo make -W]

I doubt that many know the history of the term 'dismal science.'

Thomas Carlyle used it to attack economists - John Stuart Mill specifically - that argued for an end to the slave trade and emancipation. To Carlyle the slave trade was Pareto optimal, to Mill it wasn't - at least not to the slaves :)

As David Levy and Sandra Pearrt write: "Carlyle's target was not Malthus, but economists such as John Stuart Mill, who argued that it was institutions, not race, that explained why some nations were rich and others poor. Carlyle attacked Mill, not for supporting Malthus's predictions about the dire consequences of population growth, but for supporting the emancipation of slaves. It was this fact—that economics assumed that people were basically all the same, and thus all entitled to liberty—that led Carlyle to label economics "the dismal science."

I'm with Team Mill (prescriptive), not Team Carlyle (descriptive).

> It’s intimately tied to value judgements.

Irony is dead (grin). That's why I mentioned Mondragon, for example. Start with one set of assumptions and you end up with all the money in the hands of a fraction of a percent of the population. Start with a different set, and you don't.

So drop 'prescriptive/descriptive' and try for some better understanding.

We don't understand economies or ecosystems well, yet we're trying to manage them.

I agree a carbon tax would be a good idea, except for the problem that there's little opportunity to take a little profit off of every transaction to feed the sharks.

------------

“In every big transaction,” said Leech, “there is a magic moment during which a man has surrendered a treasure, and during which the man who is due to receive it has not yet done so. An alert lawyer will make that moment his own, possessing the treasure for a magic microsecond, taking a little of it, passing it on. If the man who is to receive the treasure is unused to wealth, has an inferiority complex and shapeless feelings of guilt, as most people do, the lawyer can often take as much as half the bundle, and still receive the recipient’s blubbering thanks.” - Kurt Vonnegut in God Bless You Mr. Rosewater

-----------

http://unstats.un.org/unsd/envaccounting/eea_white_cover.pdf

"The extensions beyond standard approaches to economic and ecosystem measurement require

the involvement of multiple disciplines. The development of an ecosystem accounting

framework as described here has reflected such a multi-disciplinary effort. The ongoing work

to test and establish the relevant statistical infrastructure, to organise and compile relevant

information, and to adopt these more extensive information sets into decision making ....

"Approaches to accounting for ecosystems in monetary terms (Chapters 5 and 6) are also

described recognising that this raises additional complexities relating to valuation. In this

regard measurement in monetary terms for ecosystem accounting purposes is generally

dependent on the availability of information in physical terms since there are generally few

observable market values for ecosystems and their services...."

Just sayin' --

[In this instance, lack of economic understanding isn't the problem. We already have that. The problem is clearly political -W]

WC writes"[Your example is the std mistake that people who don’t like Ricardo make -W]"

I doubt it - since I hold Ricardo in fairly high regard. But since you are unable to elucidate your non-argument we will never know.

Well, the top 2 hits for the phrase WC uses are (1) Krugman and (2) WC. Does this clarify or further confuse what he thinks?Ricardo's Difficult Idea - MIT

web.mit.edu/krugman/.../ricardo.ht...

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

What I am concerned with here are the views of intellectuals, people who do ... to do is to make clear how few people really do understand Ricardo's difficult idea ..... there is a new trend among people who don't like conventional economics, ... economists, when they try to argue in favor of free trade, make the mistake of ...

Expert Consensus on the Economics of Climate Change ...

scienceblogs.com/.../expert-consensus-on-the-economics-of...

ScienceBlogs

Dec 9, 2015 - Economic experts believe that climate change will begin to have a .... [Your example is the std mistake that people who don't like Ricardo make ...

PS -- seems to me (utter amateur point of view) that the economics of climate change runs into four factors widely observed but not usually written up together:

1) Liebig -- Law of the Minimum: yield is proportional to the amount of the most limiting nutrient

2) Ricardo -- Local limits don't limit local growth when international trade and transportation satisfy local needs

3) Catton -- Overshoot happens when international trade lets local areas grow to where any interruption in supply of the limiting resource is a crisis

4) Murphy -- Shit happens, eventually

and I'd add (5) Systems theory says we know where the leverage points are and usually push them the wrong way.

So we get bigger fossil-fueled container ships (more eggs in fewer baskets), and bigger storms and bigger waves (climate change); does that also mean bigger rogue waves, which break container ships? I'd guess so.

Crash.

And (6) limits on information transfer are increasingly as important as limits on material trade, and <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kessler_syndrome" -- Kessler Syndrome --equally at risk for overshoot followed by interruption.

Crash ... bang ...

And (7) Any overshoot may offer an opportunity to intentionally disrupt a market for competitive purposes.

Apparently that potential is considered a feature, not a bug:

$5000 for the best essay by an American college student:

http://grasshopper.com/entrepreneur-scholarship/

"What does market disruption mean to you as an entrepreneur? What would you do to create market disruption for your business?"

I think I'm done. Someone smarter, please, continue explaining how economics and climate change will go.

[In this instance, lack of economic understanding isn’t the problem. We already have that. ]

Who is Eli to argue with the obvious.

dang.

"... The pilots also confirm what marine scientists have just started talking about: Ocean waves are becoming bigger and more powerful, and climate change could be the cause.

"We've been talking about it for a couple of years now," said Capt. Dan Jordan, who served in the merchant marine for 30 years before becoming a Columbia River Bar pilot. "Mother Nature has an easy way of telling us who is in charge."

Using buoy data and models based on wind patterns, scientists say that the waves off the coast of the Pacific Northwest and along the Atlantic seaboard from West Palm Beach, Fla., to Cape Hatteras, N.C., are steadily increasing in size. And, at least in the Northwest, the larger waves are considered more of a threat to coastal communities and beaches than the rise in sea level accompanying global warming is.

Similar increases in wave height have been noticed in the North Atlantic off England.

Unclear is whether the number and height of "rogue" waves beyond the continental shelf have increased. The existence of such freak waves, which can reach 100 feet or more in height and can swamp a large ship in seconds, wasn't proved until 2004, when European satellites equipped with radar detected 10 of them during a three-week period. According to some estimates, two merchant ships a month disappear without a trace, thought to be victims of rogue waves.

"Obviously, this is an issue we are interested in," said Trevor Maynard of Lloyd's of London's emerging risk team, which tracks global climate-change developments. "We are seeing climate change fingerprints on a lot of events."...

Well, there ya go. Lloyd's is paying attention.

Ya know there's a line about insanity being getting bad results and then continuing to do the same thing over and over again?

How about getting bad results and then continuing to rely on the same economists over and over again?

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/top-economists-rankings-un…

---excerpt follows---

JAN 4, 2016 19

The Closed Marketplace of Economic Ideas

MILAN – Imagine that you fell asleep in 2006 and woke up today. The world economy would be barely recognizable. While you were dreaming of real-estate riches, the United States and Europe were hit by the most crippling financial crisis in almost 80 years, and China’s statist economy swiftly overtook Germany and Japan to become the world’s second largest (and, despite its recent slowdown, is poised to surpass the US).

Given such massive, unexpected shifts, you might be even more surprised by what didn’t change: the way economists think about themselves and their discipline.

Support Project Syndicate’s mission

Project Syndicate needs your help to provide readers everywhere equal access to the ideas and debates shaping their lives.

LEARN MORE

To see this, one need look no further than the Ideas.RePEc.org website. RePEc (Research Papers in Economics) arguably provides the closest thing to a credible hierarchy of economists, not unlike the ATP’s rankings of professional tennis players. The site, entirely open and free (thanks to hundreds of volunteers in 82 countries), maintains a decentralized online database of around two million items of economic research, including working papers, journal articles, books, and software. Its index of influence assesses the number of citations for each author, weighted by impact and discounted by citation age (otherwise, Adam Smith and Karl Marx would likely still top the list).

Because the ranking is updated every month, RePEc enables one to track which economists are viewed by their peers as the most influential over time. ...

------end excerpt -------

https://www.economy.com/dismal/analysis/datapoints/258154/Can-Economics…

"Can Economics Change Your Mind?

Jan 12, 2016 | By Adam Ozimek

Economics is sometimes dismissed as more art than science. In this skeptical view, economists and those who read economics are locked into ideologically motivated beliefs—liberals versus conservatives, for example—and just pick whatever empirical evidence supports those pre-conceived positions. I say this is wrong and solid empirical evidence, even of the complicated econometric sort, changes plenty of minds...."