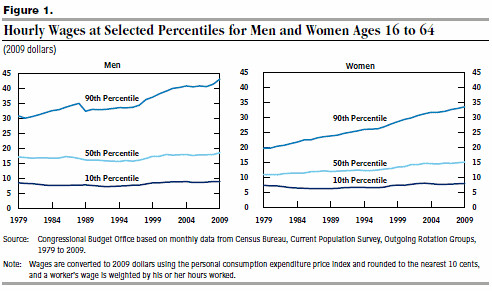

By way of Mark Thoma, we come across these two figures about wages. First, with the exception of workers near the top of the wage scale, things have pretty much flat-lined for three decades:

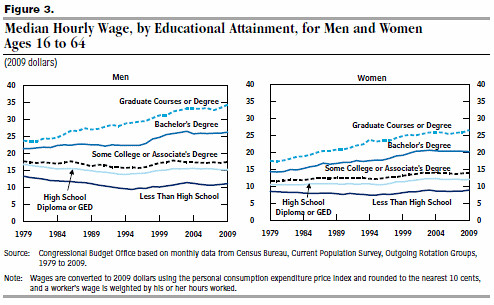

Women at the 50th percentile have seen an improvement, but keep in mind that they still lag considerably behind men in absolute terms. But the relationship between educational attainment and wage increases is stunning:

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 35% of workers has a college degree or higher. Basically, two-thirds of U.S. workers haven't seen any economic gains in thirty years. Some are worse off.

Clearly, busting teachers unions will help fix this.

- Log in to post comments

More like this

by Elizabeth Grossman

What industry employs approximately 20 million Americans, or one out of five US private-sector workers, but whose median wage has workers taking home less than $20,000 a year? Clue: It’s the same industry in which it’s actually legal to pay $2.13 an hour, for workers who…

Yesterday, the nation celebrated its workers. However, new research finds that most workers face fewer and fewer reasons to rejoice.

Last week, the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) released a new report finding that hourly wages fell in the first half of 2014 when compared to the first half of 2013…

I want to note three recent articles about science education. They may be dots worth connecting to each other, or they may not. I welcome your hypotheses, well grounded or tentative.

Via Michael Berube: "Women Gaining on Men in Advanced Fields". It seems like we've heard this kind of result…

Wages in the highly profitable fast food industry are so low that more than half of families of front-line fast food workers are enrolled in and depend on public assistance programs to make ends meet. In other words, that seemingly inexpensive burger and fries not only comes with a secret sauce,…

After controlling for inflation, why should the hourly wage for unskilled labor be expected to increase? It seems surprising to me that it hasnt shrunk more, since virtually every macroeconomic trend of the last 30 years has put adverse pressue on it. The administrations of the last 30 years, nearly all republicans, have favored policies that make it steadily easier as you get richer to stay rich and to accumulate wealth at a faster rate. So wealth continues to be concentrating in a shrinking proportion of the population. One of the principal ways of accumulating wealth in the last 30 years has been taking advantage of the growing access to the limitless unskilled supply of the third world, mostly by shifting manufacturing out of the country. It would be nice to have an administration that did not reward the rich for sending jobs overseas but it seems unlikely to happen any time soon for many reasons. I assume, pessimisticly, that every economic force active right now will continue to accelerate globalization, and the one thing the earth is not going to run out of anytime soon is unskilled people willing to work for less than you are.

@1: The flaw in your argument, which both Karl Marx and Henry Ford recognized, is that you won't get rich if nobody has the money to buy what you're selling. Ford became a rich man precisely because he paid his workers enough that they could afford to buy the product. There may be a temporary advantage to arbitraging unskilled labor, but beggar-thy-neighbor is not a sustainable strategy. That's one of the factors that led to repeated economic crises in the 19th and early 20th century.

@2, Well, yes, but the markets in foreign countries have been growing for decades. South Korea, Japan, Europe, and even Chinese - they're willing to buy our products, and often willing to make cheaper or better versions themselves.

Eric, i agree that it's not sustainable, but that is exactly what is objectionable. Once someone gets rich by transferring a project overseas, they can then use their capital to stay wealthy-- their income no longer depends on the success of the company in this country. I think our lower end workers are suffering and have a grim job and wage prognosis precisely because our american standard of living in the mid-2oth century depended on an economically more adiabatic -- isolated -- system and your argument was valid. A wider global market can offset a shrinking US market. Or it simply doesnt matter to the rich that the profits from a one-time transfer do not continue. I am not an economist, and I would truly love to be wrong about this, but your arguments from early 20th century economic philosophy suggest you arent much more sophisticated about it.

Because the GDP relative to the numbers of workers has increased. The country has become wealthier, yet virtually all of the wealth increase has been at the top. One of the main drivers of wealth increase has been an increase in productivity across the board, yet most of those who have become more productive have not reaped any benefits.

The country has become *much* wealthier--the US GDP has gone from $5.1 trillion to $12.8 trillion dollars (in constant dollars). The US has gotten 2.5X richer. But US workers aren't taking home 2.5X the pay for their work--all that new wealth has been channeled to very few people.

I think our lower end workers are suffering and have a grim job and wage prognosis precisely because our american standard of living in the mid-2oth century depended on an economically more adiabatic -- isolated -- system and your argument was valid. A wider global market can offset a shrinking US market.

But the world itself is an isolated system. As I said, the advantage to arbitraging labor is temporary. You can repeat the cycle--we are now seeing companies moving operations to countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh because China and India are "too expensive" for them. Eventually you run out of countries where you can profitably outsource, and the result is a world full of unskilled workers who cannot afford to buy what you are selling.

Your alternative scenario, in which the rich don't care that they have killed the golden goose, is more plausible. The rich already behave like that in some third world countries, and the US has been trending in that direction. Note, for instance, the rise of gated communities--they're considered normal everywhere I have visited in Latin America, but in this country they were unheard of until about 30 years ago.

Until there is once again a conscious political policy effort to make sure that all those generating the wealth gain from its generation wealth will continue to move toward the top--that is until the system becomes so top heavy there is nobody in the middle and bottom who can buy and thus no good investments to be had for those wit all the cash.

The real reason we are getting asset bubbles (and we're getting a new one in the American stock markets now) is because there is way too much cash held by a few seeking good investments and not enough demand from those who have not participated in the growing pie and so can't buy. We keep increasing capacity while shrinking the groups who would buy that capacity.

Imagine this: a company closes plants in America and ships thousands of jobs offshore. This generates a bunch of domestic cash which then goes into the banking system where it is loaned out to a class of people to buy houses they will lose when their jobs get offshored.

"why should the hourly wage for unskilled labor be expected to increase?"

That's easy. It should rise because of increased productivity which is driven by capital investment and organizational restructuring. A store clerk with a scanner at the register can scan more customers per hour. A guy with a digger can shovel more dirt than dozens. A cop guided by a GIS can fight more crime than a whole squad.

The problem is that wages have been flat since 1980 while productivity has soared. This happened back in the 1930s, after the manufacturing boom of the teens and twenties which raised productivity by two or three orders of magnitude. If wages get too far behind productivity, then it is possible to manufacture more goods than people can buy. You have to export, if you can, or you have to find an excuse to raise wages.

Kaleberg, it's not easy. You have named a factor that exerts an upward force on wages and I have named a factor that exerts a downward force on wages (near-infinite increased supply of unskilled labor--- a pool so large it's like the earth being able to ground an electric current by its mass). The problem is that if we cannot quantitate the two opposing forces (and there are others besides) we cannot predict whether the net effect is up or down. The graph would suggest they have been relatively balanced for 30 years. This is partly why economics is not a science like physiology.

So Mike, why did you post this? Economic observations like this usually elicit

(1) blame--- the rich, the Republicans, politicians in general, transnational corporations, "The System",

or (2)a proposal to change policy--- reduce access by American to the third world labor supply.

Or (3) we can play a round of "aint it awful".

Which of those 3 responses were you hoping for?

Reply to #2 posted by Eric Lund

Eric, are you really claimng that Henry Ford paid his workers enough that they could buy Fords? Have you thought about that?

The fact is that Ford's compensation policies made him nearly immune to labor unrest and interference.

Back to the original graphs. Notice that they are adjusted to 2009 dollars. Therefore, an absolutely flat line is good, not bad.

The education graphs reflect the influx of uneducated, untrained illegal aliens who have steadily taken-over the very lowest level jobs. Because of their illegal status, they are not in a position to take action to improve their positions, which is good for our economy.

Unfortunately, illegals tend to drag down the legal American workers by their presence. Why pay an American $15 per hour plus minimum benefits when you can hire a Mexican for $10 and pay him no benefits at all?

Illegal workers in the lowest paid jobs are a permanent depressionary factor on the lowest level jobs.

If you want some more bad news, look at how flat even the educated wage scales have been for the last 10 years. Virtually all of us who count on our education and ongoing wages for our prosperity will be lucky if our adjusted wages even hold steady for the next decade. It's becoming clear to everyone from teachers to physicians that the labor supply is endless and the wage climb of the mid 20th century will not continue. Lots of concern for everyone (except those who have inherited wealth or can make new money-- the GOP will no doubt continue to protect you).

If you look back to the 1930s, you would see that while the factories were empty and the workers were unemployed, the factories were still there. As the economy picked up towards the end of the decade, the factories were put back into production.

Today, the factories are gone. The machinery has been moved overseas, and the buildings stand empty or have been razed.

Besides moving jobs overseas, our businesses have moved their knowledge base overseas. China, for example, is producing the latest, most sophisticated computers and other electronics, and they are using the proprietary data we developed in the US.

In addition to purely technical knowledge, every enterprise possesses something I call tribal knowledge: the unwritten information needed to operate efficiently. We've shipped this overseas, too.

There are three generally accepted sectors of the economy: service, manufacturing, and extraction. For convenience, manufacturing and extraction can be lumped into a single sector: production.

Only production creates wealth. The service sector, while it generally facilitates production, does not create wealth; it only moves it around. That's why the GDP, as an indicator of wealth, is not reliable.

That's ridiculous. Why should a worker be paid more because his employer invested in better machinery? The employee hasn't done a thing to merit more pay.

Supply and Demand. If you have too large a supply, drop the price.

Itâs my understanding that while wages havenât grown, *total compensation* has â itâs just that all of that increase takes the form of higher health-insurance premiums paid by employers. This means that workers who get health benefits have generally seen their compensation increase, and workers without benefits generally havenât.

@1

maybe because the rich have been getting much richer over that same period of time off the backs of the workers? I believe people who do the labor to earn the money for a company deserve a fair share.

Or perhaps wages should go up so that the class of people known as the working poor (who are employed and STILL below the poverty line) cease to exist, because it is morally indefensible that so many people live that way. That is just a crappy set up for a society; its ridiculous that some people don't have to work and live in mansions while others work their whole lives and can't afford health insurance.

This is what I hate about the US sometimes, the questions people ask about the system. We live in a system of chronic underemployment and unemployment for a certain segment of the population, over employment and stagnating wages for most, and a leisurely super rich minority of less than 1% of the population. Then when the bottom 50% wants to fight over more than 1% of the wealth there are people who genuinely ask "why should their wages go up?". Do you not see that there is a common enemy here, that they have taken so much away from workers already? The richest people in the country did not always have such a monopoly on the wealth in the nation, their earnings increased while the earnings of working people decreased. The earnings of the elite business class increased while social programs and jobs went away for the rest of us. They shaped policy with their money to get more for themselves and less for everyone else. Why aren't people asking why it is that CEO salaries should go up instead of salaries for working people?

Reply to #16 posted by skeptifem:

Who said CEO's salaries should increase? Should is a judgement word, so let's drop it and ask, Why have CEO's salaries increased instead of wages for the "working people"?

First, supply. There are more working people available for every working job than there are CEOs available for CEO jobs. Just like there are far more "actors" in Hollywood than there are Oscar winners.

The cream rises to the top.

Second, welfare. Those "working people" receive government support indexed to their incomes. In other words, they have an incentive for NOT earning more, for not improving themselves. Businessmen know that if they want to advance and prosper they must work harder than the next guy; they must succeed.

DO NOT interpret this to mean that I am against all welfare. I am simply pointing out the down side of the dole.

Third, unintended consequences. Every bill passed by Congress results in unintended consequences. One of the most important of these is the reduction in healthcare available to adults under 65 due to the increase in healthcare costs since the mid-1960s. As a result, healthcare is a major factor in compensation, salary.

Where almost all government employees receive full healthcare insurance as a benefit, few private sector, "working people" receive any more than minimum. Children can more easily access free, government-provided healthcare, but the working stiff, the taxpayer in the middle, gets screwed.

If you want a rule of thumb, consider this: government consumes between fifty cents and one dollar for every dollar it distributes, spends, gives away, provides, etc. If the project involves mostly government workers, the consumption can approach 100%, with nothing measureable produced.

So a $100 million government Interstate Highway project will cost the taxpayers between $150 and $200 million, while less than 25% of the original $100 million will be paid out in wages to the "working people."

It gets worse. A program to re-educate "working people" could see every penny consumed by the government itself with no follow-up assessment. I.e., no final accountability.

Compare this to the CEO who either makes a profit or makes an exit.

It's a pity you don't exhibit a little common sense, A little common sense.

Every time you hear of a CEO getting a pay rise, you hear excuses why. Every time you hear of a worker getting a pay cut, you hear excuses why.

Oddly enough, they're considered valid. But NEVER if you swap the reasons over:

CEOs: it's a competitive job, live with it or we'll have to close down and you'll be unemployed

Workers: we need the best, so we pay the best.

The problem is that the CEO works on the old boy network and, since they have been paid millions CAN leave.

For some reason when a CEO or a Fortune 100 company says "Do it or we'll leave" it's considered fine.

Yet if you were to threaten to leave your job as a peon (so called because of what the wealthy do to you), you're "not a team player".

But you love it that way. Why? No common sense reason.

"Itâs my understanding that while wages havenât grown, *total compensation* has â itâs just that all of that increase takes the form of higher health-insurance premiums paid by employers."

But the USA pays twice as much as the European average and gets a worse health report from it.

It doesn't really help if your "total compensation" merely goes to a healthcare company whose board of directors has one of your directors on it.

NOTE: funny how these directors get five-ten director or other jobs to hold on to, each giving a really good wage. Supposedly they're motivated to do the right thing because they're going to lose their job if the company fails.

Yeah, 20% of their job...

BUT, anyhow, your idea of "total compensation" was well summed up in a Dilbert strip where a contractor told that rather than pay they'll get "intangible benefits" that are worth far more, who ripostes with "give me the lousy worthless money and give the shareholders my worthy intangible benefits instead".

Reply to #18 Posted by Wow

What is a pity is that you, an obviously intelligent if misinformed poster, waste your time composing trivial insults instead of thinking. If you had spent a little time in thought, you would realize that my post had refuted your argument before you posted.

Excuses or reasons? It's all in your point of view. If you think the worker who has invested nothing has a right to the profits, then excuses is appropriate. But if you believe that a fair day's wages is sufficient pay for a fair day's work, then reason, not emotion, is called for. Double entendre intended.

Never is a word that has no validity in reality. Find another one. Give an example.

It is competitive while the selection is being made, just like it's competitive until the star is picked for the gigabucks movie. After that, it's symbiotic where both succeed or both fail. Not so the "working people."

The best what? The best uneducated workers? The best average guy? The best unskilled

labor? Workers like that are a dime a dozen. That's reality.

I had a company that performed mowing, landscaping, and excavating. It ordinarily took me a month or two to find and hire a competent, reliable supervisor (crew boss), or a year to train one.

It took me a single phone call to the unemployment office to find a dozen strong backs. I.e. "working people."

When I needed a backhoe or dozer operator, I posted an ad in the community paper; I usually had my operator within a week, complete with resume, recommendations, and demonstrated ability.

However, when I decided to take a less active role in the business, I began looking for a competent manager; that went on for over a year. Result: Nada. I never found one. So because of that and a few other factors, I sold the company and went to riding my motorcycle and playing in my home machine shop.

One other thing, when I won a job that needed another piece of heavy equipment, I bought it and hired an operator. You can be sure that, despite the increased productivity of the bulldozer or TLB, I did not give raises to my other employees for the simple reason that they had done nothing to earn them.

Here's another consideration: competition. If I did not watch my costs and prices, my bids went up, and one of my competitors got the jobs. Then no one on my payroll got paid, including me.

You have a good case for giving more of my money to my employees only as long as you are never faced with reality.

A little common sense, the CEOs who earn the most are not the ones who are most productive. They are, instead, the ones who are most capable of taking the job. They often make decisions that are detrimental to the company; they get rewarded for - at most - increasing the bottom line in the current quarter. Their decisions are always focused on personal profit. There isn't a CEO around for a major and profitable company(1) that wouldn't sacrifice it in a heartbeat if he could make a bundle personally.

The members of the Board of Directors on many major corporations are CEOs in other companies. They all vote each other positions and "compensations". The often act to the detriment of the shareholders. They give no indication of caring about the workers.

We *should raise the question of what we "should" do. Morality is how we treat people, and therefore it is a legitimate question when considering how the workers are treated. We cannot decide what to do economically and pretend that we can ignore moral questions. Unless, that is, we are sociopaths.

We must also consider how the coming generations are treated, or don't you care about your own grandchildren? We need to leave them a moral and fair structure, and a sustainable structure: economical, political, and environmental.

You mentioned that the workers did not create the technology needed to increase the productivity. You should note that the managers did not, either. How have the increased salaries of engineers and scientists increased in the last thirty years, compared to top executives?

(1) Exceptions are those still run by the founder or his/her family, who may have a personal desire to see the company do well. When they die off or retire, the sharks move in.

Reply to #21 posted by kermit:

No argument there, but so what? A thief is a thief. I saw the CEO of [name deleted]plunder the company for two years and then move on after collecting his multi-million-dollar bonus and severance pay. I've also seen one of the lowest paid laborers walk off with power tools and equipment worth thousands. So what? That's human nature, not a rule of business.

There has been a lot of discussion comparing the Japanese practice of planning centuries ahead with the Western practice of looking at the quarterly profit statement. I move for a melding of the two: short-term and long-term planning.

The Japanese also have keiretsu. In the US we call it monopolistic and have made it illegal. Go figure.

Morality is the set of rules by which we behave as people. Morality does not apply to the conduct of a business, only the conduct of the people within that business. Those people have to determine what they will or will not do to earn profits, and if those actions violate their moral foundation, they should find alternative ways of behavior. However, you cannot force your morals on anyone else, and that is exactly what you are trying to do.

I do not recall the teaching of morality in any of the business courses I've taken.

Bankrupting otherwise profitable businesses by forcing your judgements on them does not make for a better future. A multi-trillion-dollar deficit does not show much concern for future generations. Within minimal government regulations dealing with procedure, safety, and other considerations, the free market will determine wages (price) based upon the supply of labor and the jobs demanding that labor.

FALSE. I stated that the workers did not pay for the equipment, therefore they are not entitled to a share of the profits generated by the equipment. No investment = no risk = no return on investment. If the workers were buying stock in the company, that would be another thing entirely, and I would expect them to work to increase profits and thus increase their own earnings from the stock.

Curiously, employee-owned businesses generally do much better than publicly owned, but they don't pay a whole lot more on the factory floor. I wonder why. Could it be because giving unearned pay raises is not really a good practice for a business?

A little common sense:

I see an interesting pattern here. You're quick to call out others for projecting their morality onto a situation that's controlled purely by supply and demand, but you seem perfectly happy to use words like "unearned" to describe pay shifts that are determined by the same factors. You're equating "earned" with "what the market determines."

When you buy a new piece of equipment that increases the marginal product of a worker, the value of that worker increases. The fact that you can pay workers well below their marginal product is simply a matter of supply and demand.

Conversely, imagine 90% of the labor force went blind and you were forced to pick among the remaining 10%. The price of labor would skyrocket and the wage of a worker would be very close to his marginal product. Would you say that the worker "earned" that extra pay? No. It's just market reality, just like the market reality you were fortunate enough to exploit to pay workers less than their marginal product.

In all of these cases, it's simply a matter of how owners and workers use market realities to negotiate for their piece of the profits. A generation or two ago, workers negotiated a bigger chunk through unionization and the exploitation of other international trade factors. What the graphs above show is that workers are no longer in a position of power during that negotiation--not that they're producing less or contributing less to our prosperity.

Reply to #23 Posted by: Troublesome Frog

Some good points there, but when you wrote:

You made a very basic mistake. The new equipment has not increased the value, efficiency, or productivity of the worker, it has increased the productivity of the PROCESS.

Want proof? What if the new equipment was a robot and the worker was made superfluous thereafter? Some increase that, huh?

Short of totally replacing the human, every technological advance reduces the value of the human, not the other way around. As machinery develops, the contribution of the operator becomes less and less critical until the worker is eliminated.

Well, no, by unearned I meant "didn't do anything to earn it." The business buys a new machine that increases output; the worker does nothing that he did not do before. Ergo, he has not earned a raise.

Your example of the 90/10 blindness supports my argument. Clearly, the conditions you hypothesize would cut 90% out of the labor supply, thus reducing it and forcing the price higher.

Never said they were. I don't recall commenting on worker productivity at all. In fact, Kaleberg missed the nail completely when he stated that worker pay "...should rise because of increased productivity which is driven by capital investment and organizational restructuring." Which makes no sense at all.

It's not so much a "mistake" as it is a definition from intro microecon. Regardless of the reason, the marginal product of the worker is higher than it was before. If losing the worker loses your $1M in output, that worker's price is going to be somewhere between $0 and $1M, depending on that worker's negotiating leverage. Based on that, what wage does the worker "deserve?"

Proofs done by dividing by zero usually aren't all that useful. Yes, you should pay the zero workers that you now employ up to the limit of infinity. Be careful, though. You might have a zero worker strike on your hands.

You're not thinking at the margin. You pay a worker a salary in order to get that worker to show up and work. If you don't pay that salary, the worker doesn't show up and the machine sits idle. By definition, the marginal product of that worker is whatever the output of machine/worker combination is. Again, the fact that you pay less than this is simply a matter of negotiating power, not one of productivity or morality.

How does it support your argument? Using your definition, do the remaining 10% of laborers deserve the wage increase they'll receive?

Let's go to my $1M marginal worker example: You'll clearly pay somewhere between $0 and $1M for him. What does he deserve? If the only way you can determine this is by looking at the supply of potential applicants (and I suggest that it is), the concept of "deserving" isn't a very useful one.

All productivity gains are split among everybody along the supply chain. Historically, there aren't that many cases where a single entity gets to keep all of the benefits of some increase in productivity. What we're noting is that compared to historical norms, labor is receiving a smaller and smaller piece of the benefits of a growing economy. This is unusual, given that this growth has always been determined by increases in technology and the capital stock.

There is nothing special about the last 30 years that says that labor "deserves" a smaller piece of the growth than it did during, say, the 1940s. We didn't grow back then because labor did something to "deserve" better wages. Like now, we grew because of new inventions and new investments in machinery. Yet the benefits were divided up differently.

Reply to #25 Posted by Troublesome Frog

This is getting to be a very wide-ranging discussion.

No, no, no. It's not the worker, but any worker. The less skill required to operate the process, the more warm bodies available in the labor market to fill the position. So as the technology of the machinery (the capital investment, what the company owns) advances, the value of any worker in the process decreases. Thus losing any worker is merely a hiccup in the process until another unskilled or marginally skilled worker can be hired. They are waiting in line right this minute if you haven't noticed.

Despite the clever math (which can be used to "prove" that 1 equals 2), zero workers will receive zero pay.

Right. That's what I've been saying. Supply of labor versus demand for labor. If your worker doesn't show up, he gets fired and mine gets hired...for the same wage. Call it negotiation or buying at the lowest price, but it results from economic laws.

Doesn't matter whether they "deserve" it or not. What matters is that the supply is reduced and the price (wage) goes up as a direct result, so they get a wage increase.

Correct. Competition forces the producer to share increased productivity with the buyer in the form of lower prices.

I pointed out that fact in my previous post when I noted that "Short of totally replacing the human, every technological advance reduces the value of the human, not the other way around. As machinery develops, the contribution of the operator becomes less and less critical until the worker is eliminated."

I disagree. Growth is determined by increase in profits and/or total business, given constant profit margins. Any resultant increase in stock value is due to those factors.

Increases in technology are nice, they might even increase sales and profit, but they are not the ultimate goal. Profit is the ultimate goal.

Once again, I disagree. I think the US grew out of the Great Depression because 1) our sales increased; we produced more, sold more, and made more profit; 2) we shipped approximately one-third of the unemployed workers off to fight the war; 3) after the war, the US was the only undamaged production center on the face of the Earth, so we could effectively employ the returning soldiers.

This gets to the point of the argument: Workers don't have to do anything to "deserve" a wage increase in order to get a wage increase. Exogenous variables can cause it. We agree on this, so I'm left to wonder why you referenced whether a worker "did" anything to deserve a wage increase to begin with. Wages are simply the result of market factors, many of which have little or nothing to do with changes in the worker.

The problem is now one of terminology. I'm talking economics and you're talking accounting. Captial stock and stock value are two unrelated things.

What I'm talking about is what, structurally, causes GDP growth to happen. Per capita GDP grows when workers, on average, produce more. This is a function of the capital stock and technology. It always has been. We're wealthier now than we were in 1950 because we can produce more thanks to technology and our investments in capital. Same from 1950 to 1900 and 1900 to 1850.

Workers historically didn't "do" anything to become more productive. Other factors made them more productive over time. Yet over time, those workers have gotten a share of the growth caused by that increase in productivity. An unskilled laborer today is far wealthier than an equivalent laborer in 1850, even though the laborers aren't necessarily "better" than they were then.

I won't go into the particulars of the post WWII economy because they're not especially relevant--the fact that unskilled labor doesn't make us grow has always been true. The fact that unskilled labor's slice of the pie is shrinking is new. Since the economic causes of growth haven't changed, it's interesting to ask what is driving this change in the division of returns on productivity.

I'll add one more quick note:

The notion that workers must do something to "deserve" a piece of their increasing marginal product is equivalent of saying that unskilled workers today should be living the same quality of life that they did at the beginning of the industrial revolution.

After all, they didn't contribute any of the things that made them more productive. They just became more productive because of inventions by skilled inventors and capital investments made by capitalists. Why should they get any of the increases in wealth of the past 200 years?

The cream rises to the top. We're not talking about disparity, we're talking about change in income disparity. Presumably the cream rose to the top 30 years ago as well. Has the cream gotten even better than the crop over time?

Again, welfare was 50% higher in real terms 30 years ago. This should mean the working class is even more motivated to work than they were back then. The change to welfare has provided an upward force on productivity and wages relative to 30 years ago, not a downward force.

What has changed over those 30 years? Well, taxes on the rich have gone down by half allowing them to accrue a much greater portion of the wealth. Meanwhile welfare has gone down, free trade and outsourcing has increased, and lax enforcement of worker's rights has facilitated union busting, all making working people struggle to tread water.

What about the public utility of a highway investment? It's not a make work program, it actually gets used. So it costs $150-$200 million with $100 million paid back into the economy plus savings accrued by individuals who use the service - in the range of another $100 million - so it's a $0-50 million (lets just average it and say $25 million) expected improvement to the economy. Government spending is investment; why do people always forget to factor in the value of the investment?

I simply must add something hopelessly naive. Humans have rights; property doesn't. People don't deserve higher wages because they produce more; people deserve higher wages because they are people and productivity has gone up so we can afford to help people.

Do the owners of capital deserve a ROI because they own stuff? No. We permit the owners of capital to receive some ROI because that helps the gears turn, but growth should not be the only goal of society, equity should as well.

Reverse the policy changes of the past 30 years already.

"The cream rises to the top."

When making soup, it's the scum that rises.

An increase or decrease in the labor supply is not an exogenous variable of that same labor supply. The subject was your hypothetical blindness example that directly and radically reduced the labor supply. It did not bear on the economy as a whole.

I misunderstood. I was thinking par value. You obviously meant total capital.

Doesn't your argument in your previous post contradict this?

By the way, I do not like the word "should" since it requires a personal judgement rather than objective reasoning.

Miles: You wrote

I do not feel that human values such as fairness, justice, impartiality, or equity can be applied to business or the economy any more than they can be applied to the specifications for a new aircraft or chainsaw.

Society and the economy are not identical. Economy is part of society. I am not even sure that equity can be a goal of society, but rather a goal of the individual.

I say this because I fear the application of any moral or ethical standard or judgement upon all people, especially by force of law.

"An increase or decrease in the labor supply is not an exogenous variable of that same labor supply."

Big words!

Pity you don't know what they mean.

It definitely IS external to the labour supply.

Children can't work and so far as I know, nobody (absent Athena) ever came to be born fully grown.

"I do not feel that human values such as fairness, justice, impartiality, or equity can be applied to business or the economy"

So we agree that corporations are soulless antisocial psychopaths.

The problem being you won't use a little common sense to see that this is not a good thing.

No, not at all. I think we may have strayed from the original point of the post a bit. The point of my argument is that trying to figure out what low skill employees have done to, in your words, "merit more pay" is not a meaningful exercise.

The interesting question is not whether or not low skill workers "deserve" to live the same today as they did at the dawn on the industrial revolution. The interesting question is why they have just recently stopped enjoying the fruits of our economic growth. They didn't just stop "meriting more pay" recently, did they?

I tend to agree to some extent. It's not the job of individual businesses to fix this type of problem. In fact, they can't. The ones who try would be destroyed by the competition. That doesn't mean that it's not something that we as a society should be considering.

Well, there are good economic arguments that rising inequity can end up damaging the economy as a whole, but that's another topic.

The problem I see with your position on enforcing morality through law is that you can't avoid it. No decision is still a decision. The default position is that the law enforces the current market outcome as the moral and correct result.

A better way of phrasing it would be that you fear the application of a moral or ethical standard other than the one that's currently being applied. I can understand that. I'm a strong supporter of private property rights and free enterprise. But I am concerned that we may have fallen into a dangerous equilibrium in which half of society no longer really reaps the benefits of our economic growth.