About four months ago, the Mars Rover Opportunity was driving around Mars at about 50% power, as five years of accumulated Martian dust on its solar panels was disastrously affecting its ability to acquire power:

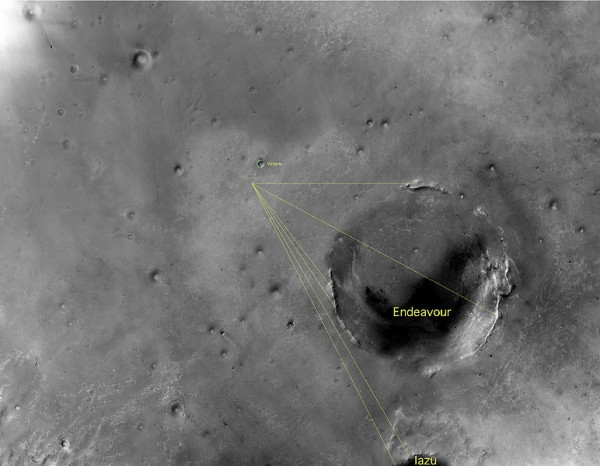

But a fortuitous, powerful gust of wind knocked much of the dust off, boosting Opportunity's power by about 40%. Because of this, Opportunity was able to continue making its way towards Endeavor crater -- the largest Martian crater that will ever be examined by any rover -- with an added power boost:

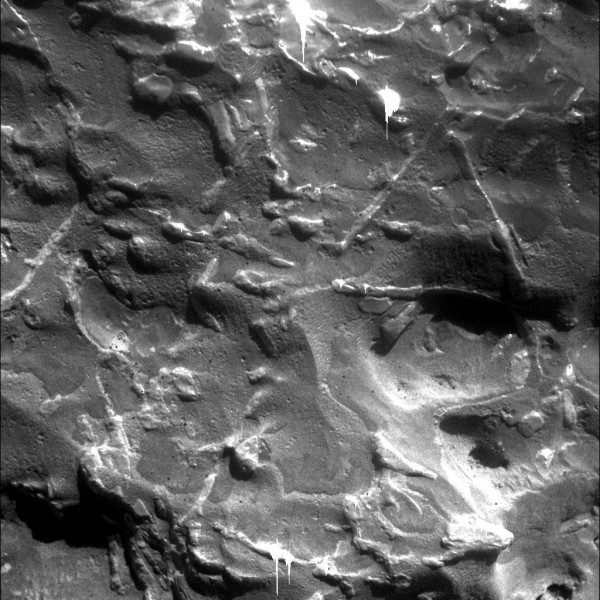

Well, a few weeks ago, Opportunity was cruising along the Meridiani Planum when it passed this unusual-looking rock, named "Block Island":

After looking at the pictures, the scientists working on the mission had determined that the rock was about two feet by one foot (the size of an old tombstone) with a bluish color to it. So, back Opportunity went to take a closer look. The findings? This thing doesn't look like it comes from Mars:

And, in fact, it doesn't. It isn't made of the same stuff that Mars is made of, and members of the Opportunity team unequivocally state:

"There's no question that it is an iron-nickel meteorite," said Ralf Gellert of the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. "We already investigated several spots that showed elemental variations on the surface. This might tell us if and how the metal was altered since it landed on Mars."

There's plenty of evidence other than composition to back up the claim that this is a meteorite. Take a close-up look at the patterns found in this rock:

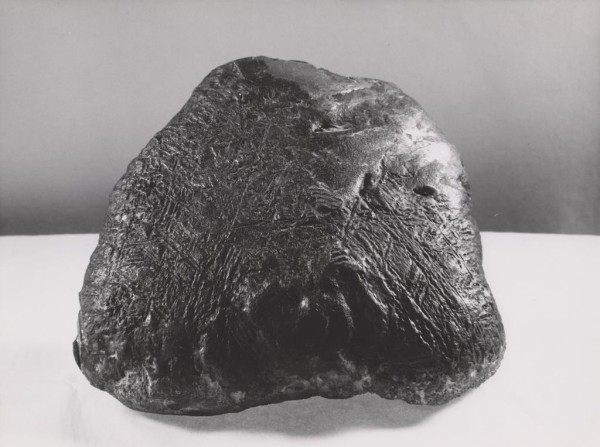

See those triangular shapes? Those shapes are smoking-gun evidence that this is a meteorite. Not only do we see meteorites on Earth with those same patterns:

We see those triangular shapes in Tunguska fragments as well. How did these patterns get exposed?

"Normally this pattern is exposed when the meteorite is cut, polished and etched with acid," said Tim McCoy, a rover team member from the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. "Sometimes it shows up on the surface of meteorites that have been eroded by windblown sand in deserts, and that appears to be what we see with Block Island."

This makes Block Island the largest meteorite we've ever found on another planet, which is impressive in its own right. But what we learn from this is even more impressive. You see, Mars' atmosphere, the way it is right now, isn't thick enough to allow meteorites this large to land:

The atmosphere is so thin that a meteorite this big would have hit the Martian surface at too great a speed, and would have broken apart from the impact. What does this tell us (and the bold emphasis is mine)?

"Consideration of existing model results indicates a meteorite this size requires a thicker atmosphere," said rover team member Matt Golombek of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Either Mars has hidden reserves of carbon-dioxide ice that can supply large amounts of carbon-dioxide gas into the atmosphere during warm periods of more recent climate cycles, or Block Island fell billions of years ago."

That's right, this is more evidence that -- billions of years ago -- Mars had a thicker atmosphere. This meteorite, which has theoretically been on the Martian surface for billions of years, could help unlock the secrets of the climate history on Mars. As Albert Yen, another Opportunity scientist, says,

We're using this meteorite as a way to study Mars. Before we drive away from Block Island, we intend to examine more targets on this rock where the images show variations in color and texture. We're looking to see how extensively the rock surface has been altered, which helps us understand the history of the Martian climate since it fell.

Opportunity is only about 4 km into its 20 km journey from Victoria to Endeavor crater, and already it's discovered the largest extraterrestrial meteorite to date, complete with evidence for a denser, thicker atmosphere in Mars' past. Remember, a denser, thicker atmosphere means a past with liquid water on Mars, which may mean a distant past with life. Not bad for a mission that started in January, 2004, with an expected life of 90 days!

- Log in to post comments

Am I the only one who is still amazed that we're looking at pictures of a rock on the surface of another planet, let alone the scientific implications of it? I suppose given my enthusiasm over SEM images of bacteria that it just means that I'm a sucker for cool pictures :p

Sweet - and I agree with JohnV, the fact that we're able to see things like this is (to me) one of the coolest things ever. Thanks for the post.

Any chance the meteor could have struck Mars a glancing blow and bounced? Could a thinner atmosphere have enough effect if the object was on a glancing path?

Fascinating stuff there rovers are finding.

Isn't there another possibility here? When a big meteor hits, a shock wave travels through it and causes solid fragments to eject from the trailing end (spallation). I believe that most or all of the Canyon Diablo meteorites scattered around Meteor Crater in Arizona are spalls from the impactor's rear surface.

So, couldn't Block Island be a small fragment thrown from a much larger impactor? If so, it tells us _absolutely nothing_ about the Martian atmosphere.

Maybe they have some good evidence against this (are those triangular features never seen in spalls, perhaps?) But neither considering the possibility that Block Island is a spallation fragment, nor explaining how it was ruled out, leaves a pretty big gap in all the reports I've seen.

The triangular shapes are Widmanstätten patterns.

As #5 said, The triangular shapesare Widmanstätten patterns., which form by the unmixing of an iron-nickel alloy on slow cooling into two phases with differing Fe-Ni ratios.

Whatever the Tunguska man is holding, it isn't iron-nickel and can't have Widmanstätten patterns. As the story makes clear, no scientist takes his story seriously, and you really shouldn't have referenced it.

Dan and NJ,

I believe you are right about the Tunguska fragments; I have a feeling that they've been faked/doctored to support Yuri's outrageous claims.

And I think that you're right that I shouldn't have referenced it, too; my apologies.

Emory, the reason that seems unlikely is that Block Island has its own pile of rubble around it, and that there are no other large meteorite fragments in the vicinity that Block Island seems to be just one of. It is always possible, however, that this is the first one in a series, and as we get closer to Endeavor, we'll find more. If we find more, that will lend some credence to your idea, but right now, the evidence supports a single small impactor from which Block Island is the largest remnant.

Wow, I am surprised that block, if it is billions of years old, even survived that long. That is one tough rock!

What a plucky pair of little rovers! Even stuck in a sand trap Spirit keeps sending data.

What if it landed in water or on water ice that may have existed in the past?

Is there any way to actually confirm the age of this object, recent vs billions of years ago, from the data we have, or can obtain with Opportunity?

Is there any hope that Spirit will ever get free of the sand trap?

What strikes me is that this putative meteorite is sitting in the midst of a flat plane. Could this be evidence for a glacial epoch on Mars? The pictures are reminiscent of a glacial erratic. If Mars had extensive frozen water, then certainly this meteorite could have impacted on a ice shelf that melted (or sublimed), depositing the meteorite on a dry lake bed and leaving no evidence of an impact. It's not clear to me where the meteorite is located in relation to the crater. The incongruous image of that meteorite on a flat terrain merits some discussion.

What Paulino said.

90 days warranty? I wish we could get hardware like that here on Earth.

Does anyone care to make an estimate of the conversion factor between human years and rover-years?

In the other nickel iron meteor, what I found striking was the discoloring of the ground around the meteor, as if something from the meteor had darkened the surrounding surface. My suspicion was UV sputtering due to halogens in the atmosphere. Aqueous corrosion would have washed the corrosion products into the soil. Sand abrasion would have blown them away.

I think its placement on the surface is best explained by ice that sublimated away.

Why no crater? It looks like the rock was set there.

i think that we should get some building done on mars because the sun well end its life but be fore that it will go into a red giant it will and it will suck up mercury and venus and then it will get to close and our water will disappear but on mars it will appear on that planet so then mars will be our home planet and then after that the sun will go into a white draft and it will be to cold and then every thing will go bad but by then we need to find another planet like the earth in the solar system and that is what i think

This is an interesting find but it doesn't tell squat about how old the meteor is nor anything about how it got there. This meter could be a fragment that came down in a high arc from very far away or could have been carried there on ice or simply landed where we see it. It could have landed with Mars present atmosphere if it came in on a very low angle to the surface say less than 20 degrees to the horizon and perhaps retrograde to Mars rotation which would reduce the impact speed. We have seen meters act just like a rock skipping across a pond here on Earth, no reason it could not happen on Mars. We need a lot more information before cranking up the speculation fevers about Mars atmosphere and what has or has not happen on Mars in the past. Hopefully, this will be one more reason to send long term maned expeditions to Mars.

I was wondering where I left that paperweight ...

Now if that space rock had been there for billions of years, how did it come to be exposed?

For argument's sake, let's say we whacked more of an atmosphere onto Mars. How long would it take for the atmosphere to dissipate to current levels? How do you reconcile an ex-big-atmosphere with a planet with relatively low mass? I mean, how did Mars get its thicker atmosphere to begin with?

@amphiox: The meteorite itself will be truly ancient (billions of years old) - and it may be possible to date it if it has long-lived radioisotope traces in it; a sample needs to be returned to earth for analysis in rather specialized instuments. However, that tells us nothing of when it hit Mars.

Is it assumed that the wind that cleared the dust covering the solar panels also removed the dust from the rock? It looks very dust-free in the photo. Or is there another explanation?

"Not bad for a mission that started in January, 2004, with an expected life of 90 days!"

No kidding. Those rovers are doing a bang up job.

There is something I am not sure matches the billion-year age: If the solar panels on the Rover got covered with dust in a mere five years exposure, how is it that the "Block Island" looks as it was gently placed there and not even close to immersed in the sand?

So we spent a billion dollars on these two rovers and couldn't afford a brush for the solar panels?! What happened? Did the guy who suggested it get the brush off? Did the guy who suggested a little blower for the panels get blown off? Seriously if we're going to send people to Mars we have to do better than this.

And no, I don't want to hear the "They were designed for ninety days and they've been running for five years" schpiel. Did the designers imagine for some reason that there couldn't possibly be any dust blowing around on Mars during the first three months? What if a dust storm like the one two years ago had blown thru in the first week? Seriously.

anonymous #17:

Mars won't be far enough away, I'm afraid. When the sun goes red giant, the difference between mars and earth will be uber crispy and extra crispy. (Unless earth gets swallowed and vaporized, of course). We'll have to be at least as far away as Titan, assuming we or anyone remotely resembling us is still around at that time.

MadScientist #20:

Is there no way to determine from the features of the meteor of its surroundings the approximate time which it impacted? (Something related to the outer surface and its possible melting/vaporization during initial entry altering its molecular structure, perhaps?)

Ian #24:

I would presume that compromises needed to be made regarding how many features/capabilities to engineer/install, balancing difficulty with likelihood or it working with overall usefulness and likelihood it would be needed with regards to overall mission goals and parameters.

For argument's sake, let's say we whacked more of an atmosphere onto Mars. How long would it take for the atmosphere to dissipate to current levels? How do you reconcile an ex-big-atmosphere with a planet with relatively low mass? I mean, how did Mars get its thicker atmosphere to begin with?

When a planet coalesces, there are volatiles present. It may also acquire volatiles from impacting comets, but I'll leave that issue for someone else; I am concerted mainly with volatiles that are trapped inside the planet when it forms, and gradually work their way to the surface via vulcanism. Now, imagine the very top of the atmosphere, thin enough that molecules very rarely collide with each other: According to the Boltzman distribution, some incredibly tiny fraction of the gas molecules present are travelling faster than escape velocity. Not many, but enough that over billions of years, the atmosphere leaks away. Hydrogen molecules and helium atoms tend to be moving 3-4 times faster than, say, a CO2 molecule at the same temperature, so they escape first. Now, the higher the escape velocity of the planet, the less this happens. But also, on a geologically active planet like Earth, gasses are constantly being released from the interior through volcanoes. So, the current thickness of Earth's atmosphere represents a dynamic equilibrium between the rate at which the Earth outgasses and the rate at which gas molecules escape into space. I do not know how quickly the Earth would lose its atmosphere if it stopped emitting gas, but it would take a long time. Geologically dead bodies like the moon and Mars do not replace the gas as it is lost, and have thinner and thinner atmospheres over time. (One estimate is that the gasses we have released on the moon during the Apollo program, instead of escaping into space, will linger with a time constant of 150 years. Someone even wrote a paper on "lunar air pollution", arguing that if there are any plans to use the Moon for ultra-high-vacuum industry, we need to plan ahead and take precautions.) Mars is much more massive than the Moon and doesn't get as hot, so it can hold on to what's left of its atmosphere for billions of years after it stopped having active volcanoes. If you gave it an atmosphere again, it would hold on to it for a very long time

"a meteorite this big would have hit the Martian surface at too great a speed, and would have broken apart from the impact."

How do we know it wasn't much bigger, and it didn't break apart, and that this isn't one of those parts?

It is not clear that Block Island has been there for billions of years. If it is old, it is possible that it fell on ice and left no crater. The hematite spherules at Meridiani Planum show no holes in their distribution on the plane that would suggest subsequent (the last 3 billion years) impacts. Ice could exist at Meridiani Planum (where Spirit is) if Meridiani planum were once a rotational pole. That would make where Opportunity is (Gusev crater area) a pole also since they are both on the equator and 180 derees on longitude away from each other. On the other hand, the chance that a rock deposited 3 billion years ago is still sitting on the surface seems a stretch. I do not see evidence of wind/sand etching of the surface as rocks subject to long periods of desert winds. If this is then recent, the meteor may have been there only about 5 Myr, a period of high axial tilt that would have destabilized the ice caps, releasing the CO2.

It looks like a dropstone. The iron meteorite was held in an ice sheet, perhaps covering a lake, and dropped into position with litte disturbance of underlying strata.

Earlier, I asked:

"Is there any hope that Spirit will ever get free of the sand trap?"

It seems the answer is yes, maybe, fingers crossed.

http://cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com/archive/2009/08/18/2034421.aspx

@Deep Field:

It is possible that the meteorite landed in softer material which has been eroded over millions or billions of years until it found itself sitting on a very large rock. The winds which can bury it in sand can also uncover it; we see that sort of thing happen on earth all the time.

@Paul: Thanks for that explanation. So if we could convert those silicates and perchlorates to oxygen at a high enough rate we can transform Mars ... hmm. I wonder if there's any hydrogen locked up in Martian minerals so we could create more water.