"Controversy is only dreaded by the advocates of error." -Benjamin Rush

Welcome back to another Messier Monday! Each week, we take an in-depth look at one of the 110 deep-sky wonders of the Messier Catalogue, from distant galaxies to nearby star clusters, from nebulous star factories to ancient globular bunches, and from stellar remnants to the rare-but-interesting anomalies. There are only three such anomalous entries out of all 110 Messier objects, and today provides us with a fantastic opportunity to take an in-depth look at one of them.

A little bit of context: back in the late 18th Century, when Messier was compiling his catalogue, professional telescopes were small in terms of aperture and light-gathering power. The primary mirrors had diameters of only 6-to-8 inches (15-20 cm) and the poor reflectivity of an old-fashioned speculum mirror, since the glass mirror didn't come into use until the 1850s. (Even a 3" amateur telescope today -- which you can buy for around $100 -- is probably superior to anything Messier ever used, although his skies were probably freer of light pollution than yours!)

As a result, objects -- even at maximum magnification -- appeared tiny to him and were often difficult to resolve; it's a wonder that 107 of these 110 objects actually do turn out to be genuine deep-sky wonders! But today, I'd like to highlight one of the three oddballs: Messier 73. Here's how to find it.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

As the months progress onwards towards the December solstice, the Summer Triangle of Deneb, Vega and Altair head farther and farther towards the western horizon after sunset. Meanwhile, the bright star Fomalhaut hovers above the southern horizon. If you look halfway between Fomalhaut and Altair, there are a number of naked-eye stars that can help guide you towards Messier 73. In particular, there are four rather bright stars near the imaginary line connecting them: two north of the line and closer to Fomalhaut, and two south of the line and closer to Altair.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Sadalsuud and Deneb Algedi are the two bright ones closer to Fomalhaut, while α Capricorni (a double star) and Dabih are the two bright ones closer to Altair. In the middle of that region enclosed by those four stars, two slightly less bright -- but still naked eye -- stars can guide you to your destination: Albali (closer to Altair) and ν Aquarii (closer to Fomalhaut).

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

There are actually three interesting objects in this vicinity: the globular cluster Messier 72, the recently deceased star that formed the Saturn Nebula, and today's object, the difficult-to-find Messier 73. What should you look for, if you're poking around in this star field?

Image credit: Rick Beno of Conferring With the Sky Observatory, via http://www.conferringwiththesky.org/.

Image credit: Rick Beno of Conferring With the Sky Observatory, via http://www.conferringwiththesky.org/.

This appears to be a tiny cluster of four stars of approximately the same brightness (one is slightly dimmer), described by Messier as:

Cluster of three or four small stars, which resembles a nebula at first glance, containing very little nebulosity.

If you can locate it for yourself, it looks like this.

Now, this is really interesting. On one hand, most of the open star clusters we see in the night sky contain hundreds or even thousands of stars, but only a handful of relatively bright ones that can be easily resolved in an instrument of the size-and-quality that Messier had at his disposal. One can hardly be upset at Messier for thinking -- especially if he thought he saw a little nebulosity around this object -- that there was probably a star cluster here.

On the other hand, it's well-known that star clusters tend to be short lived. The vast majority of them are completely dissociated, with their component stars strewn through the galaxy, in less than a billion years. It stands to reason, however, that when a star cluster does dissociate, there ought to be a few small groups that remain together, bound by their own gravity.

Could this collection of four bright stars (with possibly more below the limits of Messier's instruments) be the very first such object to be discovered?

Image credit: © 2006 - 2012 by Siegfried Kohlert, via http://www.astroimages.de/.

Image credit: © 2006 - 2012 by Siegfried Kohlert, via http://www.astroimages.de/.

Or would this simply turn out to be a very statistically unlikely coincidence: four stars of almost identical brightness, standing out against the black backdrop of space, separated from one another by less than a twentieth of a degree (or 2.8 arc-minutes, to be precise)?

Image credit: Fred Espenak of http://astropixels.com/.

Image credit: Fred Espenak of http://astropixels.com/.

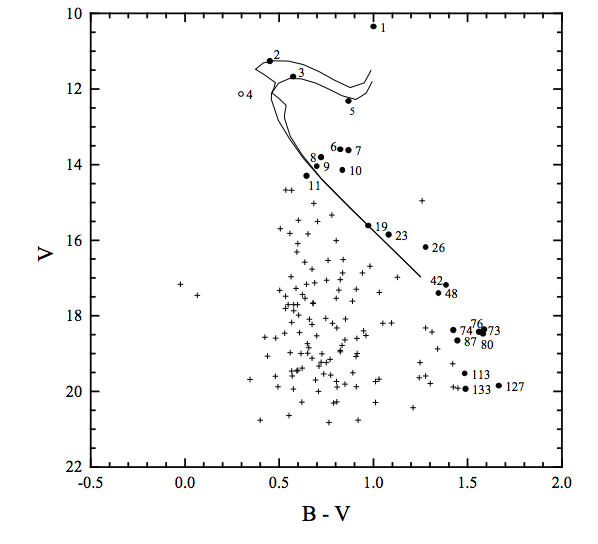

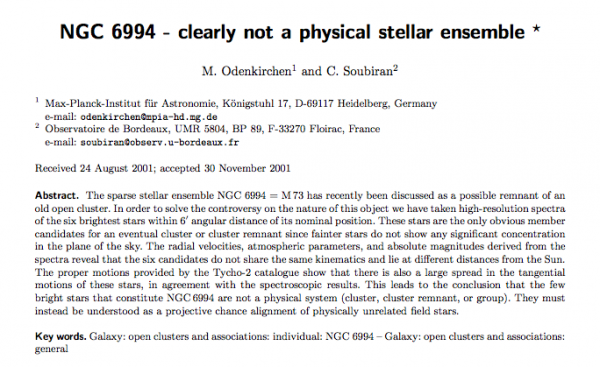

There were many throughout the centuries who derided this object's inclusion in the Messier catalogue, much like the other anomaly we've looked at here: the double star Messier 40. But this is no obvious mistake; it would take more than two centuries to figure it out. As recently as 2000, a high-resolution photometry study indicated that this was a 2-or-3 billion year old cluster remnant, which looked like it followed a characteristic Hertzsprung-Russell curve.

Image credit: L. P. Bassino, S. Waldhausen, and R. E. Martínez, Astronomy & Astrophysics 355, 138 (2000).

Image credit: L. P. Bassino, S. Waldhausen, and R. E. Martínez, Astronomy & Astrophysics 355, 138 (2000).

It wasn't until two years later that a high-resolution spectroscopic study was done on this cluster. By looking at the spectra of the six brightest stars near the center of the cluster (including the four main ones), they could tell whether they were gravitationally bound and whether they were the same rough age-and-metallicity. The results?

The stars are all at different distances, moving with speeds that indicate they're unbound, have different atmospheres and are in no way related. This does, however unlikely it seems, confirm that this is merely a chance alignment of stars, and it also means that we have not yet discovered a smoking gun for a tightly-bound remnant of a once-open cluster.

But they're out there; it just happens that Messier 73 isn't one of them.

A chance, unlikely alignment of stars never seemed so interesting, and at last a 200+ year controversy can be laid to rest! It's just a collection of four stars that aren't connected at all, and yet, I can't help but be fascinated at the possibility that there are chance alignments out there that aren't chance at all, but are rather the once-majestic remnants of long-gone star clusters!

In any case, that brings us to the end of another Messier Monday! Including today's entry, we've looked at the following objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back again next Monday, where another deep-sky wonder -- and another glimpse deep into the Universe -- awaits!

- Log in to post comments

We have optical binaries in astronomy don't we? Double stars that aren't really connected but are just very close inline of sight as seen from Earth.

So .. can we maybe call M73 an optical cluster?

Yeah, same thing that happened to the Coathanger!

On behalf of all us amateur astronomers, thank you for this tremendous resource of Messier Monday!