"I should like to lie at your feet and die in your arms." -Voltaire

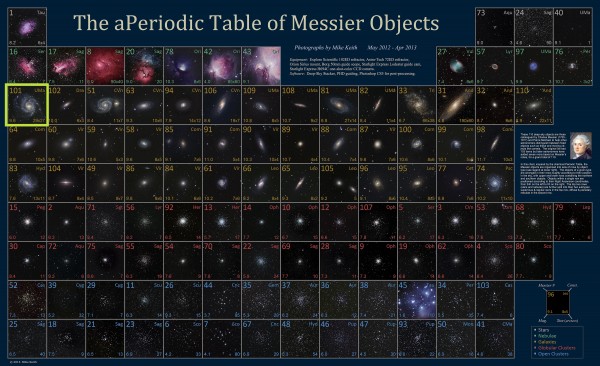

Every object that we look at for Messier Monday has its own flavor, its own qualities, and its own unique characteristics. By far the most numerous of the 110 deep-sky objects making up the Messier catalogue are the galaxies, of which there are 40. It's best to observe them on moonless nights, as their surface brightness is spread out across a large area, and even a crescent Moon's presence in the night sky can make all but the brightest of these galaxies invisible to the eye, even in good equipment.

Out of all the deep sky objects in the Messier catalogue, none has proved more frustratingly elusive to me, personally, than the great Pinwheel Galaxy, located just above the handle of the Big Dipper. Although it's quite large and close, the low brightness of this galaxy makes it a challenge for many, especially in light polluted areas. During this (virtually) moonless Messier Monday, here's how to find it.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

If you can find the Big Dipper in the sky, you'll be well on your way to finding Messier 101, the famed Pinwheel Galaxy. The last star in the handle is the bright blue Alkaid, while the one next to it is the double star Mizar/Alcor, just barely perceptible as two separate stars by those with perfect vision. (Through a good enough telescope, you might see anywhere between three and up to six stars when you look at this pair!)

If you can find Mizar/Alcor, you'll be star-hopping your way towards Messier 101 in no time.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

If you can separate Mizar and Alcor, you can follow the imaginary line they create from Mizar (the brighter one) towards Alcor and beyond to the four naked-eye stars you see above. There's no need to remember their names, although it might help you to remember the colors go: blue, red, white, and then blue again.

From that last blue star, you're going to want to jump upwards again about another two degrees, in the same direction you went from the Mizar/Alcor pair to the first of the naked-eye stars.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

And in a very nondescript patch of sky, if your equipment and the skies cooperate, you might just find one of the closest face-on spiral galaxies in the entire night sky.

It took a long time to find it, too; it wasn't discovered until 1781 by Messier's assistant, Pierre Méchain, who identified this as one of the very last objects added to Messier's original catalogue. Through their equipment at the time, it might have looked something like this.

Image credit: Axel Nevens, via his site at http://axelnevens.be/.

Image credit: Axel Nevens, via his site at http://axelnevens.be/.

Very faint, and hard to see against the background star field; it was described in the Messier catalogue as a "nebula without star," and it's probably that only the brightest, central region was visible to Messier and Méchain.

But as telescopes became more powerful and instrumentation improved, so did our views of this object.

Image credit: Russell Sipe of Jupiter Ridge Observatory, via http://www.sipe.com/jupiterridge/.

Image credit: Russell Sipe of Jupiter Ridge Observatory, via http://www.sipe.com/jupiterridge/.

By 1851, Lord Rosse was able to identify a number of these objects as having a spiral structure, M101 among them. Located a mere 21 million light-years away, only five other Messier galaxies beyond our local group are closer. And this galaxy has a spectacular story to tell all unto itself.

Image credit: Ken Crawford of RC Optical Systems, via http://gallery.rcopticalsystems.com/.

Image credit: Ken Crawford of RC Optical Systems, via http://gallery.rcopticalsystems.com/.

The grand spiral arms are clearly visible in this face-on spiral masterpiece, and pinkish regions -- harbingers of newly formed stars -- highlight various locations therein. There are about 3,000 such star-forming regions known to date, an astounding number for a spiral galaxy! And at 170,000 light-years in diameter, this galaxy is about 70% larger than our Milky Way.

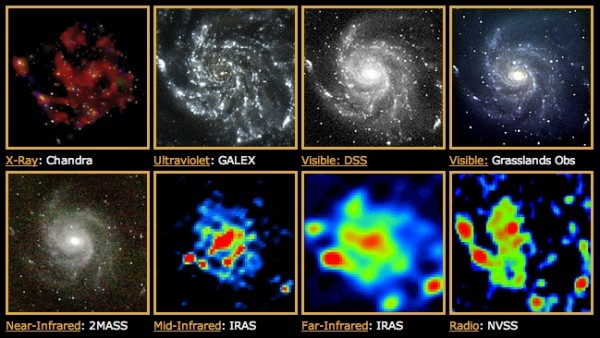

We can learn some interesting things by looking in other wavelengths, such as ultraviolet.

The small central bulge -- which contains about 3 billion solar masses -- is almost invisible in the ultraviolet, telling us that there's only minimal star formation taking place there. Instead, the locations of the youngest stars are outlined. The fact that they both trace out the spiral arms of the galaxy as well as creating large, extended swoops tell us that M101 has most probably recently cannibalized a smaller galactic neighbor.

This would explain all the star forming regions and would also lead to the prediction that there should be an enhanced number of supernovae in this galaxy.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons user Thunderf00t, via http://thunderf00tdotorg.wordpress.com/.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons user Thunderf00t, via http://thunderf00tdotorg.wordpress.com/.

Well, not only is that true -- we've seen three since 1900 -- but just two years ago the closest supernova since 1987 went off in the Pinwheel galaxy!

Looking at multi-wavelength views, we also see an abundance of X-ray sources, a huge amount of cool, potentially star-forming dust in the infrared, and faint emissions in the far-IR and the radio! There's something missing, though, and that's intense X-ray or radio emissions from the galactic center!

In other words: no supermassive black hole at the center, which is unexpected and surprising!

This galaxy also holds a remarkable distinction: it is (as of 2008) the most accurately imaged spiral galaxy -- via Hubble -- of all-time!

Image credit: ESA / NASA, Davide De Martin, and K.D. Kuntz (GSFC), F. Bresolin (University of Hawaii), J. Trauger (JPL), J. Mould (NOAO), and Y.-H. Chu (University of Illinois, Urbana).

Image credit: ESA / NASA, Davide De Martin, and K.D. Kuntz (GSFC), F. Bresolin (University of Hawaii), J. Trauger (JPL), J. Mould (NOAO), and Y.-H. Chu (University of Illinois, Urbana).

You can find the full-resolution image here, but let me just take you on a little tour through the center of this behemoth, made up from more than fifty individual Hubble images! (And what you see below is actually a 15x reduced resolution; the true original is here!) Check out the huge number of background galaxies when you can see through the disk, and check out the huge number of stars and star clusters when you can't!

Hang on...

Image credit: ESA / NASA, Davide De Martin, and K.D. Kuntz (GSFC), F. Bresolin (University of Hawaii), J. Trauger (JPL), J. Mould (NOAO), and Y.-H. Chu (University of Illinois, Urbana).

Image credit: ESA / NASA, Davide De Martin, and K.D. Kuntz (GSFC), F. Bresolin (University of Hawaii), J. Trauger (JPL), J. Mould (NOAO), and Y.-H. Chu (University of Illinois, Urbana).

And with that spectacular slice, we'll wrap up another Messier Monday! Including today’s entry, we’ve looked at the following objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back again next Monday, where instead of one of the largest Messier galaxies, we'll peek in on one of the smallest, which are just as interesting, but in an entirely different way. Only here, of course, and only on Messier Monday!

- Log in to post comments

Magnificent images here. Jaw-droppingly marvellous. Thanks.

How times have changed: about 40 years ago, black holes were considered theoretical & somewhat speculative, and now we remark that it's odd to find a galaxy that doesn't have a supermassive black hole at its center.

Does anyone have a decent hypothesis as to what's at the center of M101? Possibly a low-mass black hole, or something else?

And yes, awesome pictures. The Hubble and its photos may have done more to promote greater awareness of the cosmos than just about anything in living memory, or at least anything since the first "blue marble" photos were taken.

Why haven't anyone done shower curtains of these Messier catalog overviews? Maybe it's difficult to have a black shower curtain, compared to the periodic system shower curtains

@G #2: The short answer to your question about what's at the center of M101? "Not much."

A quick search of arXiv turned up a 2010 follow-up article by Kormendy et al. (http://arxiv.org/abs/1009.3015) which does a broader survey of galaxies in our neighborhood (< 8 Mpc), and finds that "pure disk" galaxies (i.e., without a central bulge) are relatively common, and that they consistently do not have a central SMBH (they present very low upper limits for any compact central mass in several of these galaxies).

The authors point out that this presents serious problems for the current model of galaxy formation via hierarchical clustering.

Thank you so much for the star hopping help! I can't wait to try this. I've been looking for M101 unsuccessfully for a while. I didn't realize it was so faint and that the right conditions are important. The next really good night I have I'm going to find it!