Stung by some rather odd language on wikipedia at [[Two New Sciences#Infinite sets]], I'm reading the bits about infinity in "Two New Sciences" (Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences aka Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche, intorno à due nuove scienze, 1638) via the translation available at http://galileoandeinstein.physics.virginia.edu/tns_draft/tns_001to061.html. If you look at the oldid of the wiki article, you'll see the familiar problems: that all Galileo's ideas have been translated into the language of modern (set) theory that he likely would not even have understood; and that the article is a travesty of what he actually thought - it makes him anticipate Cantor in a way that I don't think he did (and so I've fixed it). Anyway, lets read him, remembering that, approximately, The same three men as in the Dialogue carry on the discussion, but they have changed. Simplicio, in particular, is no longer the stubborn and rather dense Aristotelian; to some extent he represents the thinking of Galileo's early years, as Sagredo represents his middle period. Salviati remains the spokesman for Galileo. That is also from the wiki article, but I'll trust it nonetheless, because I know no better.

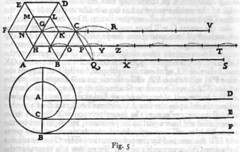

It probably helps to have searched for "infinit" in that text, which on Chrome at least helpfully highlights all the occurences, and marks up the scroll bar, so you can see where the discussion occurs. We start around page 68. Galileo is groping towards ideas of limits. He is trying to understand what happens when two concentric cylinders roll along (apparently, this is a classic Aristotelian problem): if the outer one, B, doesn't slip, then the inner on, C must. But what does "slip" mean, he wonders? An infinite number of infinitely small slips? He motivates his discussion by considering polygons, shown in the pic, and then considers polygons with more and more sides.

It probably helps to have searched for "infinit" in that text, which on Chrome at least helpfully highlights all the occurences, and marks up the scroll bar, so you can see where the discussion occurs. We start around page 68. Galileo is groping towards ideas of limits. He is trying to understand what happens when two concentric cylinders roll along (apparently, this is a classic Aristotelian problem): if the outer one, B, doesn't slip, then the inner on, C must. But what does "slip" mean, he wonders? An infinite number of infinitely small slips? He motivates his discussion by considering polygons, shown in the pic, and then considers polygons with more and more sides.

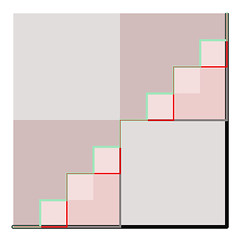

But there is a problem, which I'll try to illustrate here with my picture of a square (someone must have a better picture of the same idea). Consider the paths across the square: starting with the outer one (black), then the one using lines of half side (dark grey), half again (red) and so on down to the smallest I've drawn in a fetching shade of pale green. The limit of these paths is the diagonal (clearly). But the lengths of all of these paths is the same: 2 (assuming a unit side to the square). But the length of the diagonal is sqrt(2). So, as we know, f(lim(s)) != lim(f(s)), where f is a function (in this case "the length of") and s is a sequence (in this case, of paths).

But there is a problem, which I'll try to illustrate here with my picture of a square (someone must have a better picture of the same idea). Consider the paths across the square: starting with the outer one (black), then the one using lines of half side (dark grey), half again (red) and so on down to the smallest I've drawn in a fetching shade of pale green. The limit of these paths is the diagonal (clearly). But the lengths of all of these paths is the same: 2 (assuming a unit side to the square). But the length of the diagonal is sqrt(2). So, as we know, f(lim(s)) != lim(f(s)), where f is a function (in this case "the length of") and s is a sequence (in this case, of paths).

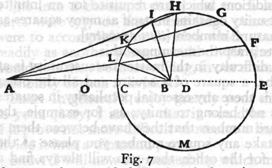

Aside: Galileo is uneasily aware of problems like this; he uses the somewhat more complex example shown here, where we draw a circle based on some points (see p 84), whose radius approaches infinity as we move the point C towards O, finally becoming a straight line. He doesn't resolve that problem, merely uses it as an example, and doesn't answer his question Now what shall we say concerning this metamorphosis in the transition from finite to infinite?

Aside: Galileo is uneasily aware of problems like this; he uses the somewhat more complex example shown here, where we draw a circle based on some points (see p 84), whose radius approaches infinity as we move the point C towards O, finally becoming a straight line. He doesn't resolve that problem, merely uses it as an example, and doesn't answer his question Now what shall we say concerning this metamorphosis in the transition from finite to infinite?

So Galileo ends up with his explanation as "The line traversed by the larger circle consists then of an infinite number of points which completely fill it; while that which is traced by the smaller circle consists of an infinite number of points which leave empty spaces and only partly fill the line". Which is meaningless.

There is also a failure to separate out the maths from the real world: SALV: ...Thus one can easily imagine a small ball of gold expanded into a very large space without the introduction of a finite number of empty spaces, always provided the gold is made up of an infinite number of indivisible parts. SIMP. It seems to me that you are travelling along toward those vacua advocated by a certain ancient philosopher. SALV. But you have failed to add, "who denied Divine Providence," an inapt remark made on a similar occasion by a certain antagonist of our Academician. I don't think this is fatal (at least not as far as I've read) but it does introduce the possibility of confusion (and as SIMP points out, of conflict with Da Man and Da Church).

Now, comparing infinities: SIMP. Since it is clear that we may have one line greater than another, each containing an infinite number of points, we are forced to admit that, within one and the same class, we may have something greater than infinity, because the infinity of points in the long line is greater than the infinity of points in the short line. SALV. This is one of the difficulties which arise when we attempt, with our finite minds, to discuss the infinite, assigning to it those properties which we give to the finite and limited; but this I think is wrong, for we cannot speak of infinite quantities as being the one greater or less than or equal to another.

This is wrong (in modern terms). With suitable definitions, comparing infinities is fine; we say and prove that the "number of points" in a line of twice unit length is "the same as" the "number of points" in a line of unit length. SALV, however, undertakes to prove his point, but drops down into the integers to do it. The example is a now familiar one (did he originate it? I doubt it; this implies not) that if we consider numbers and their squares, there appear to be "more" plain numbers than squares; and yet we can map in a 1-1 way from numbers to their squares, so there must be "the same" number (the modern solution, if you don't know it, is that if you can construct a 1-1 map from one set to another then they have "the same number of elements" (cardinality). And this works, and is free of contradition).

So it isn't entirely clear why Galileo insists infinities can't be compared; in the case of the integers, he has almost everything he needs to get the right (i.e. modern, more powerful, interesting and useful) answer; but he funks it. Perhaps because he wasn't really interested in the integers; they were merely a helpful expository device to him. He already "knew" the answer he wanted in terms of the continuum. But it is harder to reason about the reals.

Update: I have a thought about where Galileo went wrong. He was too much trapped in the way of thinking that the things you are reasoning about are known and all you need to do is to think more carefully. After all, people have been thinking about this for millenia. What he failed to see - what everyone failed to see - was that what was missing was a definition of equality for infinite quantities. Once you see that, then you see that you have the definition to hand - 1-1 correspondence - and all problems resolve themselves. But realising that you don't understand equality is the hard part. In this, it is very like Einstein realising that a definition of simultaneity is needed.

Refs

* Galileo and Leibniz: Different Approaches to Inï¬nity

* Me discussing infinity and stuff with E. Ockham

Galileo was better scientist and he was speak truth

The reals arn't really real.

[All numbers are constructed -W]

So he has constructed a mapping of one infinite set onto another, but since each element of one is larger than each element of the other he rejects the identity of the number of points in one set with that in the other. This is very, very basic, and very, very hard to accept. Try teaching it.

[I tried my nine year old but I don't think she is ready for thinking these thoughts yet -W]

"God made the Integers; all the rest is the work of man."

[Kronecker, yes. But he only said that because he didn't like Cantors completed infinities - it isn't a respectable opinion -W]

There's a little evidence that some non-human animals have integers (in the sense: have some mental abstraction of small positive integers). But as you say, all numbers are constructed, that is obviously so. Real numbers are just what you get if you insist, in any of a number of ways, on continuity. Just as complex numbers are what you get if you insist on polynomials having solutions.

Mathematicians fall into three classes: discrete mathmos (e.g. combinatoricists) who hold that the integers (by extension, the ordinals and/or cardinals) are the One True Numbers, continuous mathmos (e.g. analysisists (?), quantum mechanicists (?)) who hold much the same opinion about complex numbers, and the rest, who are freaks and weirdos.

But what I was actually going to say: what's this about concentric cylinders?

[I explained it, didn't I? Remember Aristotle doesn't really have a concept of speed -W]

"The History of Numbers" is an interesting read even if the reviewer for the Notices of the American Math. Society didn't care for it (or find it thoroughly accurate).

No, I don't understand the concentric cylinders at all. Is it one cylinder inside another?

[Oh, sorry. Think of it as a railway wheel with a flange, perhaps. The inner circle is the wheel in contact with the rail. The outer is the flange. And you imagine having two rails: one on which the inner cylinder rolls, and one on which the outer rolls (in the book version, the no-slip is on the outer; if you're imagining railway wheels then the no-slip is on the inner) -W]

"4

There's a little evidence that some non-human animals have integers (in the sense: have some mental abstraction of small positive integers)"

Some chimps and even birds (Parrots IIRC) have demonstrated that they can tell numbers in the abstract, that is they note that the number of items are different if asked what's changed and have shown ability to subtract when asked what will change if N things more are removed.

Given you'd find it almost impossible to find a human who doesn't share your language that could do any better in a test you devise, this seems pretty good evidence that nonhumans can manage the trick of abstract counting.

. . . if we consider numbers and their squares, there appear to be "more" plain numbers than squares; and yet we can map in a 1-1 way from numbers to their squares, so there must be "the same" number (the modern solution, if you don't know it, is that if you can construct a 1-1 map from one set to another then they have "the same number of elements" (cardinality)

Mathematicians would not be happy with this, as at best it demonstrates carelessness with the meaning of well-defined terms. Namely, it conflates one-to-one with one-to-one correspondence. They are not the same (I thought they were for years, in part by lose language like this). What you mean to say is:

"if you can construct a 1-1 map from one set ONTO another then they have "the same number of elements" (cardinality)"

The words one-to-one (a.k.a. injective) and ONTO (a.k.a. surjective) together make a bijection (one-to-one correspondence) and with that, you conclude that two sets have the same cardinality.

To summarize, use "one-to-one correspondence" when you mean bijection, as one-to-one is just one half of the requirement!)

[I think you're being overly pedantic in a general setting. "a 1-1 way from numbers to their squares" implicitly means ONTO -W]

There is no bijection from numbers to their squares. E.g. if f:R->R is defined by f(x)=x^2 (a map from a number to its square), then the function is not 1:1 (Visually the graph doesn't pass the horizontal line test)

Proof that f is not 1:1.

Let a,b be real numbers and suppose f(a)=f(b), then we have a^2=b^2, but a does not have to equal b, as (-a)(-a)=a^2 and (a)(a)=a^2, hence the function is not 1-1 (injective)

Not sure about the history of numbers, if negative numbers were not around in Galileo's time, then he could not have noticed this.

[We're not talking about R. We're talking about the non-negative integers. Of course Galileo knew about negative numbers -W]

Are there then infinite points of social interaction along the line from here to an 80% reduction in CO2 emissions?

Kent Slinker, there certainly is a bijection between the set of real numbers and the set of squares of real numbers. (It just happens that "squaring" isn't it.) And there's a bijection between positive integers and squares of positive integers. You're trying to nitpick something that is perfectly clear and sensible; no mathematician should have a problem understanding what William wrote.