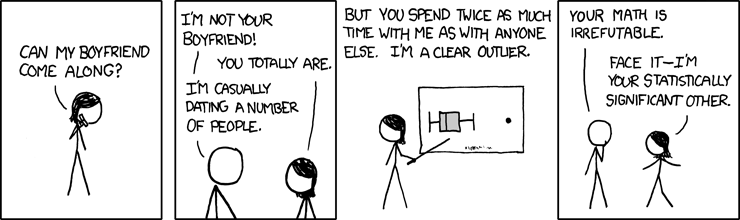

![]() What do this cartoon and the latest edition of PLoS One have in common? Well, reading Bora's blog this week I saw an article entitled, Risks for Central Nervous System Diseases among Mobile Phone Subscribers: A Danish Retrospective Cohort Study and my ears perked up. We have been mocking the idea that cell phones cause everything from brain cancer to colony collapse disorder and it's always fun to see what cell phones are being blamed for based on weak associations and correlations.

What do this cartoon and the latest edition of PLoS One have in common? Well, reading Bora's blog this week I saw an article entitled, Risks for Central Nervous System Diseases among Mobile Phone Subscribers: A Danish Retrospective Cohort Study and my ears perked up. We have been mocking the idea that cell phones cause everything from brain cancer to colony collapse disorder and it's always fun to see what cell phones are being blamed for based on weak associations and correlations.

In this article the authors identified more than four hundred thousand cell phone subscribers and linked their cell phone use to their medical records in the Danish Hospital Discharge Registry which has collected records of hospitalizations since 1977. They then tried to identify an association between cell phone use and various CNS disorders over the last few decades. These disorders include epilepsy, ALS, vertigo, migraines, MS, Parkinsons and dementia, a broad spectrum of diseases with a variety of pathologies and causes. Basically, they're fishing. Well, what did they find?

Here's the summary of the associations they identified:

First the ones they think are significant showing a statistically significant increase in migraine and vertigo among cell phone users. Note the SHR column as the effect they noticed on risk. SHR less than one would be demonstrate an ostensibly "protective" effect or decrease in that disease in the population, and a SHR greater than one would demonstrate a "harmful" or increased correlation between the disease and the cell phone use.

Second, a host of other associations they dismiss as a healthy cohort effect:

Cell phones are correlated with increased vertigo and migraine, but decreased epilepsy, vascular dementia, Alzheimer disease, with no effect on MS or ALS.

As with many such fishing trips for statistically significant correlations they found something, which isn't that surprising, if you've read PLoS, and or our coverage of John Ioannidis' research. The critical fact to take away from his writings is that if you study anything, anything with statistics you're going to find statistically significant correlations. In fact if you found nothing that would be strange as you would predict that if you study enough variables, roughly 5% should be statistically significant just by chance, and the nature of the scientific literature and the "file-drawer effect" is that this number goes up as researchers are more likely to publish big effects and "file away" the papers showing no effect even though the results are true.

So, the question that has to be asked isn't whether or not such correlations can be found, but should we care? After all, what is the physiologic mechanism by which cell phones are increasing migraine or decreasing epilepsy? What is the proposed biological pathway that cell phone radiation is interacting with? Why is there not a dose-response? Longer exposure shows less of an effect which makes even less sense because when phones went from analog to digital, the power output was greatly decreased. So early adopters that got even larger exposures but don't show worsening migraine or vertigo.

How does any of this, make any scientific sense whatsoever? What does an article like this contribute other than more misinformation dumped carelessly on the public from the over-interpretation of statistical noise? Why PLoS? Why are you making our lives harder?

I'm sad to say that this article in PLoS will be responsible for more such alarmism and nonsense and frankly would not have been published if the editors had been paying attention to, well, PLoS. I might have to go find Isis' picture of that Teddy bear for this one.

Joachim Schüz, Gunhild Waldemar, Jørgen H. Olsen, Christoffer Johansen (2009). Risks for Central Nervous System Diseases among Mobile Phone Subscribers: A Danish Retrospective Cohort Study PLoS ONE, 4 (2) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004389

It seems to me that by publishing papers such as this, PLoS is reducing the "file-drawer" effect as you call it, making it more feasible to do meta-analysis on these types of studies or to spur follow-up work to verify the results and hash out the root causes.

That is one argument for the study but the conclusions of the authors should be that there is no plausible link between cellphones and CNS disease as the effects seen make no biological sense. When one publishes these as evidence of potential harm, rather than realistically looking at these effects as no more than statistical noise the damage is done and these will be cited as "evidence of harm" as it were.

I would argue that instead that such epidemiological studies should be held to a higher standard, such that they must start from a position of a biologically plausible hypothesis, and then look for associations, because after all fishing expeditions will always find some association that is prone to misinterpretation and abuse. As it stands such results add nothing to our understanding of these diseases, and will only contribute more misinformation about the role of cell phones and health.

Dr. Mark, how much cellphone use would you recommend to cure my vascular dementia?

Yeah I'm on the fence. Definitely not advocating that journals become filled with such studies. At the same time I think if you approach it from the standpoint of "we did a large survey and found , however our statistical methods have a false positive rate of and therefore further analysis & verification is required", then the study has some value for the broader scientific community as well.

You are probably on the right track to say that the editors should have done more to neutralize the way the findings are presented. It seems that the authors do a reasonable job of pointing out some of the limitations of the study (with the notable exception of the statistical methods), and are careful to say that their weak positive correlations need to be studied in more detail. I'm guessing that the issue you are driving at is how the popular press will take this data and run with it, declaring that anyone who handles a cell phone now probably has nonstop migraines and vertigo.

Maybe we need a rule, you cannot publish a study like this unless you have the money in hand to do a much better study focusing on any correlations you find.

Mark: Of course it's not true that every data set of at least 100 measures will have 5 that are statistically significant. That would require independence, which is not usually true. But that's not the main point. The problem of multiple comparisons is not as simple as your naive view suggests. Suppose you do a study and look at three things, each of which you believe should be related to the independent variable. Are they subject to the multiple comparison problem? How about if you then measure 5 more, that on the basis of some data you think might be related? Are they also subject to multiple comparisons? Why or why not? Since every day there are millions of measurements made throughout labs all over the country, are they subject to multiple comparisons? Does your analysis mean that every day where there are a million pieces of data collected, there are 50,000 spurious results? How to correct for multiple comparisons is a notoriously difficult problem. But just dismissing results on that basis is not a solution.

Note, too, that the 95% confidence intervals are intervals around a point estimate. What they really mean is that for the assumptions of the test, if you were to take many independent samples and calculate a confidence interval each time, 95 of 100 of them would cover the true value (i.e., it is a coverage probability). This is not the same as saying that 5% of the measurements would be statistically significant.

So here is a study that was done and showed some associations but you don't accept them because you don't believe any association exists, right? This cries out for a Bayesian viewpoint, which says: here are my priors and here's the evidence. Now here are my new priors. But evidence doesn't seem to mean anything in your analysis. That seems to me to be a problem with your view (I am agnostic about this study, which I haven't read , but I have read you analysis of it).

Just wait until some mass media outlet runs a story featuring this article...

The study does not tell us whether the mobile phone buyers were harder hit by migraine or vertigo before they bought their mobile phones. As a migraineur I bought a phone a long time ago, as it gave me the possibility to call my husband if a migraine attack hit me and I was unable to drive home, or risked vomitting all over the train etc.

As always, a statistical correlation does not tell us which is the cause and which is the effect. It is likely that migraineurs invested in mobiles early, simply because these phnoes are handy, when you get an attack at an inconvenient time.

For the benefit of those of us who don't know much statistics, can you explain the following:

independence

multiple comparisons

Thx

How to buy prescription drugs...? My doctor prescribed vicodin for a while back, my back hurts, I think it is a great help, but in my country it is difficult to find, it is paramount to have my information on it and found information about findrxonline.com the medicine, because it provided me.

It's staggering to think how much of our "knowledge" comes from "studies" like this one. We seem to have endless appetite for stuff like this. And many times we treat it the way we treat conflicting weather forecasts: we believe the one we like better. What counts is how we use this information, or any other information for that matter, in the choices we make. Revere is right that the proper way to do so is to update our beiefs with Bayes theorem and think carefully about our utilities.

All I ask is that we remember that (1) the conclusions of this study MAY be correct (even if unimportant) and that (2) even properly controlled randomized trials can also give us incorrect (and unimportant) conclusions.

This would be more trouble if it wasn't nigh on impossible to remove a mobile phone from it's user. However i look forward to the Daily Mail full page expose of this terrible threat to our brains. Which will be amusing given the average Daily Mail Reader doesn't actually have much to lose.

How would the authors conclude that from their study?

FWIW, I think the authors' conclusion is reasonable:

Further attention seems warranted - there is something going on: the directions of the migraine and vertigo effects are consistent in the different groups, so it's not simply noise.

One commenter on the article has suggested that cause and effect might be the other way round: people suffering from migraines may have been early adopters, because they felt a bigger need of a mobile, in case they had a bad migraine and wanted to call for treatment.

Marylin: Statistical independence means that the outcome of one test has no effect on the probability of the outcome of another test. For most outcomes this isn't true. The chances you have vertigo are higher if you also have migraines, for example.

The multiple comparison "problem" (NB: many epidemiologists and statisticians can't agree what kind of problem it is or how to fix it) is that assuming there is no effect and assuming that outcomes are unimodal and assuming the conditions of the statistical test (e.g., that all outcomes are from a normal [bell curve] distribution) and assuming no bias or measurement error -- assuming all these things and more, some or many of which may be wrong -- then if you use a 5% criterion for "statistical significance" and you do 100 tests ("multiple comparisons") you will get (on average) 5 results in the tails of the distribution. Are those tests "false positives"? Depends how you interpret being in the tails and all the other things. Some people try to "correct" for doing more tests by making the critiorn of significance more stringent, say instead of 5% much less, even going so far as to divide 5% by the number of tests. This Draconian manouver is called a Bonferroni correction and is overly conservative. I doubt very much if Mark did it for his thesis results (you did do statistical evaluations, didn't you Mark?) since that would likely have destroyed his positive results (requiring, for example, that if he measured ten things in all he would have had to use p<.005 for his level of significance). But I'll let him answer that.

I do not really understand the specific statistics used here, as I did not take a closer look at the paper, but is that not what the Bonferoni correction is for? If you have a lot of tests, as in this fishing case, you only accept P values that are much lower than the usual 5% or 0.05 - for 20 different tests, say, P should be <0.25% or 0.0025. That usually takes care of a lot of false positives.

(obviously it was a bad idea to use a smaller-than-symbol)

I do not really understand the specific statistics used here, as I did not take a closer look at the paper, but is that not what the Bonferoni correction is for? If you have a lot of tests, as in this fishing case, you only accept P values that are much lower than the usual 5% or 0.05 - for 20 different tests, say, P should be less than 0.25% or 0.0025. That usually takes care of a lot of false positives.

Thanks.

Those reading carefully would see a Bayesian approach was exactly what I was advocating. That is the whole point Ioannidis is making.

Such an approach would seem to me to mean this isn't even information, but merely noise.

Go and read the editorial policy of PLoS ONE before you criticize them for doing pretty much exactly what they promise to do.

Mintman - as Anonymous pointed out, the Bonferroni is horribly conservative. An additional problem is that it assumes independence, and this is clearly not the case for this data: the different estimates for each disorder are clearly correlated. There are (far too many) alternatives that perform better, but the lack if independence is going to screw most of them.

mark - I'm not sure that a Bayesian approach per se would actually help. I think the problem is more one of getting people to think about their results. The Bayesian approach perhaps formalises that, and forces people to think, but I don't see that it has to be done in such a rigid framework.

In this case, it might actually be a hindrance. Your prior would have a large mass at zero effect, but the data suggests there is an effect, i.e. there's something going on. The issue is whether it's mobile phones causing people to be sick, or whether it's something else. I think your zero prior should be on a more restricted hypothesis, but still allow other factors to affect the data.

Bob, I suspect that every result in the paper was a youth effect and they failed to separate out the variables correctly. Phones aren't doing anything here, they're just accidentally studying population demographics.

And anon, it's the editorial policy of PLoS One to publish crap? I didn't realize. Once I read that's their policy I'll apologize.

Mark, have you read this one?

http://lablemminglounge.blogspot.com/2009/02/are-mobile-phones-bad-for-…

I don't see anything intrinsicly implausble about cell phone users have more migraines that non-cell phone users.

They are bloody annoying.

You write: "So, the question that has to be asked isn't whether or not such correlations can be found, but should we care? After all, what is the physiologic mechanism by which cell phones are increasing migraine or decreasing epilepsy? What is the proposed biological pathway that cell phone radiation is interacting with?"

But should I remind you that for quite a number of years, statistical links between higher mortality rates and behavioural traits (such as smoking) were dismissed as no explanation was (yet) found between tobacco and, say, heart diseases.

So, yes, statistical tests of all kind are useful to explore all potential associations event if jumping to spontaneous conclusions is preposterous. Further disaggregation of data (by age and other characteristics) will sort out the current interpretative speculations. I'm afraid your comments may at this point appear more speculative than the paper itself.