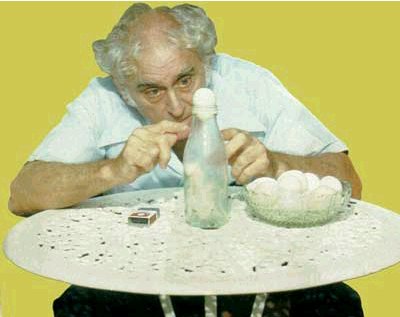

Others have their own view, but the best science show on TV ever was done in Australia. In fact, it wasn't a show, it was a man - Professor Julius Sumner Miller. Miller was a student of Einstein's, and he got his start in the US and Canada before taking up a position in the Physics department at the University of Sydney, and in the early 1960s, he began doing what became an Australian institution - a science show, for school kids (in their blazers and ties), which actually got the kids to answer the questions themselves. His catchcry, in that raw eastern American accent, "Why is it so?" became so well known that even today you can use it in Australian discourse and everybody (who lived here from 1963 to the mid 1980s) knows immediately who you are talking about.

He also did a series of Summer Science Schools. I would stay home on a Saturday morning (or was it Sunday?) during the summer just to watch it. He did one on space travel, and another on chemistry if memory serves.

Miller was a marvel. He would explain Galileo's physics with hoops, wheels and balls, challenging the innate Aristotelian physics we all have with tricks and demonstrations, but he would always ask the audience what would happen first. The shock we got when the large hoop and the small ball took the same time down the incline served to embed the lesson. He would burn things, heat things, chill things, use hard boiled eggs, pieces of paper and all manner of visual aids. Anyone wanting to show science on TV today would do well to get the videos and learn from him.

It was a more innocent age, when it was assumed that kids wanted to learn (and their parents would as well), and not just be entertained. With his shock of wild Einsteinian hair, he was a totem of science for severla generations. Nothing on TV now comes remotely close.

Miller's wife started a foundation in his name. The motto, as true now as ever, is "People look, but they do not see".

Having never seen it, I can't comment on that show. All I know is that, although some other programmes have come very close, none that I have seen have ever surpassed The Ascent of Man.

Bronowski was great, yes. But Miller didn't report on science, he showed children how to do it, and to see.

Da-amn. That "Why is it so?" link to his shows online is a gem of a website. What a compelling character. Thanks for sharing.

Out here in Canada I grew up with "Square one!" as the TV show of choice for geeklings. The be-all end-all most-kickass segment of the show was "Mathnet," a mathematically minded spoof of Dragnet. And people thought Numb3rs was breaking new ground. As if.

Online clips here: http://ellery.info/mathnet/

I take the link back. Catch a full episode at youtube here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXiehPXhy5g

Thanks for the memory, John. Julius Sumner Miller brought Physics alive for me. His acerbic, provocative, in-your-face style challenged the viewer and shouted "Don't just accept or assume, observe and reason!" It was a lesson that has stayed with me for life. Many things are interesting and informative, but few have such a profound influence.

A large hoop and a small hoop maybe? A ball should accelerate quite a bit faster than a hoop when rolling down an inclined plane. (The moment of inertia per unit radius and mass is smaller.)

Thank you! That's what I recalled, but edited my memory because I thought it must be wrong. Miller was a better teacher, and I a worse student, than I recalled...

Not necessarily full-on science instruction, but one of the best sciency shows I've seen (and loved as a child) was the Discovery Channel's airing of the British _Connections_ with James Burke. It didn't just teach the science, but placed discoveries in a social milieu and traced the way that seemingly abtruse knowledge (such as, say, the range of motion of a fired shell on a battlefield) could lead to earth-shattering scientific and technological advances (such as, say, the digital computer). I haven't seen it in awhile, and perhaps my now-jaded eyes would find it a bit facile and simplistic, but it had a huge impact on me growing up.

The greatest popular science instruction I've ever seen, though, wasn't a TV show, but the series of essays Asimov did in F&SF magazine, covering virtually every realm of science with quite a bit of history and technology thrown in for good measure. I still read those today, and while they may be a bit dated at times, I'd recommend them heartily to children of a certain age to learn more about science.