tags: Close Encounter with a Whale Shark in the Gulf of Mexico, marine biology, field research, research, technology, whale shark, Rhincodon typus, satellite tags, Gulf of Mexico, BP, Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, University of Southern Mississippi, streaming video

Whale Shark, Rhincodon typus, feeding in the Gulf of Mexico.

Image: Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Whale Shark Research.

Despite being the largest fish species in the world, measuring over 40 feet in length and 35 tons in weight, whale sharks are quite mysterious. We know they are plankton filter feeders, and we recently learned that we can identify individuals by the pattern of dots and bars on their bodies, but otherwise, we know very little about these animals. For example, in just 1996, we learned that these sharks are ovoviviparous (their young grow in egg sacs inside the body but are born live) after capturing a female pregnant with 300 pups. But we still know almost nothing about them, including their population size. So to learn more about them, researchers are attaching satellite tags to whale sharks and taking a tiny tissue sample for DNA work. This video shows this process as it occurred with one whale shark feeding at the surface of the water in the Gulf of Mexico.

| Swimming with a whale shark off the Alabama coast |

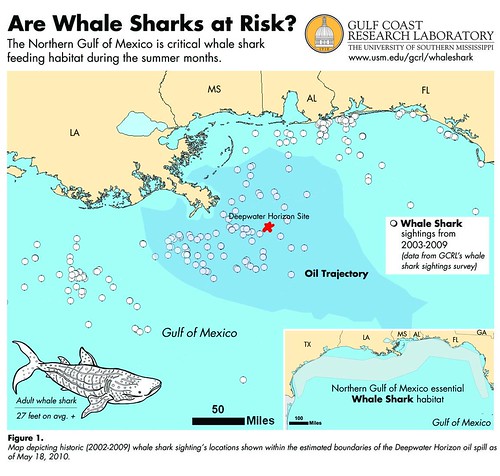

Last week, scientists spotted a group of roughly 100 whale sharks in the Gulf last week, feeding on the surface over a deepwater area off Louisiana called the Ewing Bank that apparently is untainted by oil from the Deepwater Horizon. But this week, there is sad news that at least three whale sharks are swimming in oil just a few miles from the gushing wellhead.

"Based on all the information I'm getting, they are doing the normal things regardless of the oil. The idea that sharks have these evolved senses that will protect them -- well, they haven't evolved to detect oil," said [Eric Hoffmayer, the University of Southern Mississippi scientist who found the large aggregation last week.]

He tagged whale sharks on the Ewing Bank in June of last year. The satellite trackers showed that some of the animals spent that July migrating hundreds of miles toward the Alabama coast and Florida Panhandle. If they follow the same route this year, it would carry them straight through the heart of the spill [...]

"Last year we had two sighted off Florida and Alabama that were from Honduras and Belize," Hoffmayer said. "That means these oil impacts are not only for the Gulf population, but for the Caribbean and maybe even further. The implications are pretty big here." He said that high Gulf temperatures and the position of the offshore Loop Current mean conditions this year are similar to those that drew the sharks to the area last summer.

"If that migration pattern holds true this year, the sharks will have to travel through the oil to get to Alabama," Hoffmayer said. "That's a serious concern. These guys are surface feeders. They swim at the surface with their mouths open. Will they be ingesting oil?" [Ben Raines, Press-Register]

Oh, there is one more thing that we do know about whale sharks: Like all shark species, these magnificent animals lack swim bladders, so for example, when they die from ingesting oil, their carcasses sink to the bottom of the sea and are never seen -- no possibility of washing ashore -- so we have no way to determine how many are being killed by the BP disaster.

Unfortunately, these satellite tags are expensive: each costs $4,000, and they are the only way we can learn more about the movements and habits of whale sharks. This year, these tags will probably provide the only record of their exposure to oil.

"We're going to miss our window if we don't get our tags out soon," Hoffmayer said. "These animals are in peril."

I strongly encourage you to donate to support this vital research (donation links at bottom of that page). Whale shark sightings should be reported to Hoffmayer at 228-872-4257 and you can learn more about this research at the Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Whale Shark Research site.