![]() Climate change is not just about surface warming and glacial melting. The carbon dioxide that human activity is pumping into the atmosphere also dissolves in the world's oceans, slowly increasing their acidity over time. And that spells trouble for corals.

Climate change is not just about surface warming and glacial melting. The carbon dioxide that human activity is pumping into the atmosphere also dissolves in the world's oceans, slowly increasing their acidity over time. And that spells trouble for corals.

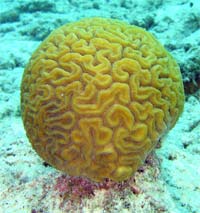

Corals may seem like immobile rock, but these hard fortresses are home to soft-bodied animals. These creatures - the coral polyps - build their mighty reefs of calcium carbonate using carbonate ions drawn from the surrounding water. But as the water's pH levels fall, these ions become depleted and the corals start to run out of their chemical mortar. The upshot is that in acid water, corals find it hard to build their homes.

Scientists have predicted that if carbon dioxide levels double, the reef-building powers of the world's corals could fall by up to 80%. If they can't rebuild quickly enough to match natural processes of decay and erosion, the reefs will start to vanish.

Now, Maoz Fine and Dan Tchernov from the Interuniversity Institute of Marine Science, Israel, have found that they have a way of coping with homelessness. They grew some fragments form two European coral species under normal Mediterrenean conditions, and others in water slightly more acidic, by a mere 0.7 pH units.

Those that spent a month in the acidic tank were quickly transformed. The skeleton dissolved and the colony split apart. The exposed and solitary polyps, looking like little sea anemones, still remained attached to rocky surfaces. When the going gets tough, the tough clearly go soft.

Even without their protective skeletons, they survived for over a year and seemed to be going about business as usual. They thrived, they reproduced normally and they still kept the symbiotic algae that allow them to produce energy through photosynthesis. And when they were put back in normal conditions, they readily gave up their independence and re-formed both colonies and hard shells.

Even without their protective skeletons, they survived for over a year and seemed to be going about business as usual. They thrived, they reproduced normally and they still kept the symbiotic algae that allow them to produce energy through photosynthesis. And when they were put back in normal conditions, they readily gave up their independence and re-formed both colonies and hard shells.

Fine and Tchernov's findings suggest that corals may be able to survive upcoming climate changes by adopting soft-bodied, free-living lifestyles. And there is evidence that they have used this trick before. The hard shells of coral reefs fossilise easily, but the fossil record still has large gaps where no reefs are found. These may represent periods of time when corals were biding their time in their soft-bodied phase instead.

But while this new discovery is cause for hope, it should not be cause for complacency. Even though the corals themselves may persist in another guise, the vast diversity of species that depend on them may go for good if their reefs disappear.

Reference: Fine and Tchenov. 2007. Scleractinian coral species survive and recover from decalcification. Science 315: 1811.

Very interesting!

This is the issue that really scares me ... of course things always turn out differently than we can extrapolate. Your post highlights that. Nature is always one step ahead of the human mind.

The ability to reform colonies and skeletons after normal conditions resumed depends also upon the symbiotic association with algae. Skeleton building is more efficient with the algal partner present. But what if the corals expel algae as temperature of the water rises as it is expected with global warming? Did the experiment control for temperature?