phage

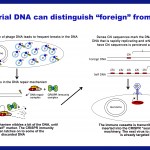

Foreigner or native-born? Your immune system discriminates between them, as do those of bacteria. Yes indeed, bacteria do have immune systems – pretty complex ones at that. And like any useful immune system, the bacterial ones must have a good technique for distinguishing “foreign” from “self.”

You may even have heard of the bacterial immune system: It’s called CRISPR, and it’s used in biology research around the world for DNA engineering and genome editing. CRISPR normally inserts short DNA sequences taken from phages – viruses that invade bacteria – into special slots called spacers within…

We were just getting used to the idea of our digestive tract as an ecosystem. There are 10 times as many bacteria in our gut as there are cells in our bodies, and the ecological balance between the different types might affect everything from our tendency to gain weight to our general health and susceptibility to various diseases.

Now, a Weizmann Institute researcher has exposed a whole new layer of this ecosystem: the viruses – called phages – that infect our gut bacteria.

Dr. Rotem Sorek and his team identified hundreds of these phages in the human gut. They were able to find them thanks to…

Viruses and bacteria often act as parasites, infecting a host, reproducing at its expense and causing disease and death. But not always - sometimes, their infections are positively beneficial and on rare occasions, they can actually defend their hosts from parasitism rather than playing the role themselves.

In the body of one species of aphid, a bacterium and a virus have formed a unlikely partnership to defend their host from a lethal wasp called Aphidius ervi. The wasp turns aphids into living larders for its larvae, laying eggs inside unfortunate animals that are eventually eaten from…

When the bacteria that cause anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) aren't ravaging livestock or being used in acts of bioterrorism, they spend their lives as dormant spores. In these inert but hardy forms, the bacteria can weather tough environmental conditions while lying in wait for their next host. This is the standard explanation for what B.anthracis does between infections, and it's too simple by far. It turns out that the bacterium has a far more interesting secret life involving two unusual partners - viruses and earthworms.

A dying animal can release up to a billion bacterial cells in every…