"Tomorrow is the most important thing in life. Comes into us at midnight very clean. It's perfect when it arrives and it puts itself in our hands. It hopes we've learned something from yesterday." -John Wayne

There's a lot to look forward to on the precipice of the new year, and many of us will be up until midnight to ring it in. Well, if you're up that late, why not step outside and take a look at one of the deep-sky wonders of the Universe that won't be visible in the early part of the night for months! This Messier Monday, a near-moonless sky will greet you until the pre-dawn twilight, and that makes it a perfect time to go on the hunt for the deepest, most extended objects visible in the night sky.

Image credit: Ole Nielsen of http://www.ngc7000.org/ccd/messier.html.

Image credit: Ole Nielsen of http://www.ngc7000.org/ccd/messier.html.

So let's introduce you to the brightest member of one of the many galactic groups visible from Earth: the distant spiral galaxy Messier 96. Here's how to find it at midnight tonight. (Or tomorrow night.)

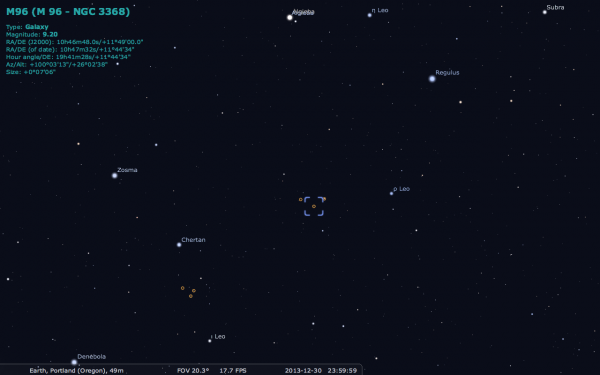

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Rising over the eastern horizon at around 10 PM tonight, the constellation of Leo is highlighted by its brightest members, the blue Regulus and Denebola, the 22nd and 61st brightest stars in the night sky. Although there are many other bright and naked-eye stars visible in Leo, looking midway between these two brightest members will get you a long way towards locating Messier 96.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

To do a little better, you can draw an imaginary line between Regulus and Denebola and another one between the naked-eye stars Chertan and ρ Leonis, and where they'd intersect is the rough location of Messier 96. But if you need a little extra guidance -- extended objects are dim, after all -- there's a slightly dimmer naked-eye star just a little bit south of the line connecting Chertan to ρ Leonis, and it's less than 2 degrees away from M96.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

Image credit: me, using the free software Stellarium, via http://stellarium.org/.

The star 53 Leonis (labeled "l Leo" above) isn't the brightest star in Leo, but it's still easily a naked-eye star. The three Hipparcos stars labeled above are easy to spot in a pair of binoculars or a low-magnification telescope, and if you look with deep, wide-field eyes at this region of space, a wonderful sight begins to appear against the clear, dark skies. (As always, click on all images for a full-size, giant experience.)

Image credit: © 2013 Scott Rosen's Astrophotography, via http://www.astronomersdoitinthedark.com/.

Image credit: © 2013 Scott Rosen's Astrophotography, via http://www.astronomersdoitinthedark.com/.

There's an entire group of galaxies here -- the M96 Group -- where Messier 96 is the brightest member at the bottom-center of this image. (The two next brightest, at the upper left and lower right, are the Messier objects M105 and M95.) These galaxies aren't just grouped together visually, they're all located between 35 and 41 million light-years from us, and all receding from us at speeds between 640 and 910 km/sec. This small collection of galaxies is estimated to be somewhat more massive than our local group, even though the individual galaxies are all smaller than both our Milky Way and Andromeda.

But for the rest of today, let's focus not on the group that bears M96's name, but on the individual galaxy itself.

Image credit: © - Copyright 2009 - Fort Lewis College Observatory, via http://www.fortlewis.edu/.

Image credit: © - Copyright 2009 - Fort Lewis College Observatory, via http://www.fortlewis.edu/.

Discovered by Messier's assistant Pierre Méchain in 1781, it was added to Messier's catalogue four days later, where he described it as a:

Nebula without star, in the Lion, near the preceding: this one is less distinct, both are on the same parallel of Regulus: they resemble the two nebulae in the Virgin, Nos. 84 and 86. M. Méchain saw them both on March 20, 1781.

Its distance was highly uncertain for a very long time; was this a relatively large galaxy that was somewhat far away, or was it a somewhat smaller galaxy that was significantly closer?

For a relatively close galaxy like this, it's actually quite a challenge, because different types of observations can lead you to different conclusions. You can measure its recession velocity (from its redshift) and use Hubble's law to infer its distance, but there are large uncertainties for nearby galaxies due to peculiar velocity. You can use correlations from its rotation speed (the Tully-Fisher relation) to infer its distance, but the uncertainties are large there, too. Other methods, like Surface-Brightness fluctuations or the Fundamental Plane relation, have large errors at this distance as well.

Image credit: RC Optical Systems, via http://gallery.rcopticalsystems.com/.

Image credit: RC Optical Systems, via http://gallery.rcopticalsystems.com/.

Ideally, you'd be able to resolve individual stars in this galaxy, and simply use what's known about them to measure that distance directly. But for a very long time, that was technologically impossible.

Until, that is, the Hubble Space Telescope came along and did exactly that.

By measuring variable stars directly in M96, they were able to determine that this galaxy is about 36.5 million light years away, with an uncertainty of only about 3 million light years, an improvement by about 80% over previous measurements. This means the galaxy you see above is around 66,000 light years in diameter, or about 2/3 the size of the Milky Way.

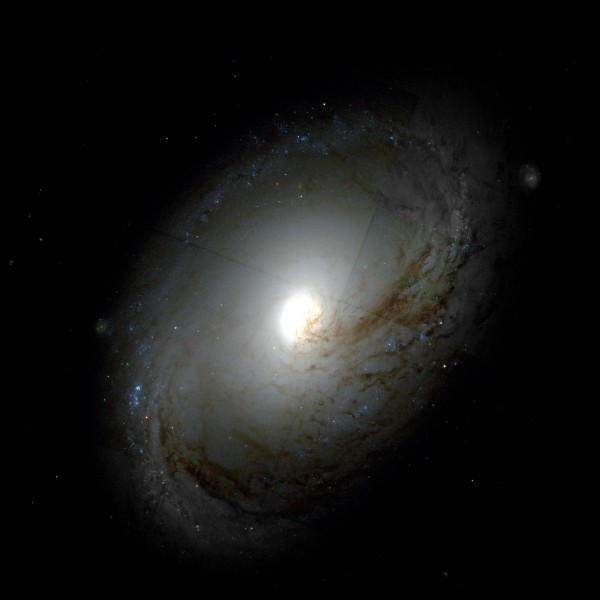

Still, this galaxy is doing something ours isn't, as some spectacular images bring out.

Image credit: Adam Block / Caelum Observatory, acknowledgement Jay GaBany, via http://www.caelumobservatory.com/.

Image credit: Adam Block / Caelum Observatory, acknowledgement Jay GaBany, via http://www.caelumobservatory.com/.

There are much fainter, extended outer arms that extend more than 100,000 light-years in diameter, as well as the characteristic pink emission lines that indicate intense star formation along the brightest parts of the spiral arms. You can also see some prominent dust lanes and -- if you look carefully -- some smaller spiral and elliptical galaxies also present.

But what could be causing the intense star formation and extended outer arms? Quite simply: the gravitational interactions with the other galaxies in this group!

The other galaxies you see in this picture, above, are actually distant background galaxies from well outside the M96 group; the gravitational interactions causing these extended features, as well as the star formation and the asymmetrical dust distribution are most probably from the other major galaxies -- M95 and M105 -- in the group.

Even in the bright core of the galaxy, huge open clusters, asymmetric dust lanes and star-forming regions are clearly visible.

There's definitely a supermassive black hole at the center of this one, although its mass is highly uncertain, and there was a supernova observed here very recently: in 1998. (Although usually supernovae are Type II, particularly in galaxies undergoing intense bursts of star formation, and this one -- SN 1998bu -- was a Type Ia. The Universe is full of surprises!)

The Hubble Space Telescope has actually looked at this galaxy a number of times, although a professionally processed image has never been released. So I went to the Hubble Legacy Archive myself, and pulled out the best image I could find, and here's what I managed to create! (As always, click for an even higher-resolution version!)

I really love how the young, bright blue stars shine through along one of the major spiral arms in this version, and I hope you get a chance to enjoy this midnight wonder of the new year's sky! So that will wrap up the year's final Messier Monday, and I truly hope you've enjoyed it! Including today, we’ve looked at the following Messier objects:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

I'd tell you to come back next week, but you'd be better off coming back sooner than that, because there's a big announcement coming for the new year, and I don't want you to miss any of the joy and wonder that the Universe has to share with you! Happy new year one and all, and I'll see you again very soon!

- Log in to post comments

It's about 1:00 am here in northeastern Minnesota and stepping outdoors to contemplate shining objects in the sky right now would be too dangerous to risk because it's -35 degrees on the other side of my door. That's about what it's been for the past couple of nights, and that's about what's predicted for the next couple, too. I'll content myself with the words and images you've posted here. Thanks! :-)

I took the liberty to post-process your composition from hubble archive. Hope you don't mind. Free to use it since it's yours :) I just gave it a face lift ;) The details are enhanced, noise reduces, colors corrected and haze reduced also.

Hope you like it and happy new year :)

http://s14.postimg.org/ksudrl527/Hubble_cropple_HLA_2.jpg