Some towns have all the luck. Brainerd, Minnesota, population ~13,000, was previously famous as the home of Paul Bunyan, and the setting of the Coen brothers' film, Fargo. Little did I know it had another claim to fame: its very own brand of mysterious diarrhea. All about it after the jump.

Some towns have all the luck. Brainerd, Minnesota, population ~13,000, was previously famous as the home of Paul Bunyan, and the setting of the Coen brothers' film, Fargo. Little did I know it had another claim to fame: its very own brand of mysterious diarrhea. All about it after the jump.

Brainerd was the site of the first outbreak of this eponymous diarrhea back in 1983. It is described as an idiopathic syndrome--meaning that we don't have a clue what causes it. The diarrhea is acute in onset, explosive and watery, can last for months, and doesn't respond to antibiotic treatment. Since its recognition, 8 other outbreaks have been recognized, linked to raw milk and untreated water. Two new CID papers (found here and here) describe additional outbreaks of the illness.

The Texas outbreak occurred beginning in April of 1996, and with 117 cases is the second largest reported outbreak of Brainerd diarrhea. This took place in Fannin County, Texas, a farming community northeast of Dallas in the Red River Valley. In an attempt to identify risk factors contributing to the outbreak, investigators conducted two case-control studies. In the first, they contacted those who had been diagnosed with Brainerd diarrhea in order to determine exposures, such as food, water, animals, etc., and compared them to control subjects who were matched by age and telephone exchange. From this initial study, they zeroed in on a local restaurant as a potential source of the outbreak, and carried out a second study of patients who'd eaten at the restaurant in order to narrow down specific food exposures at the location, and water was taken for analysis from the restaurant's kitchen tap, water dispenser, and ice machine in late July of 1996 (almost 4 months' removed from the start of the outbreak).

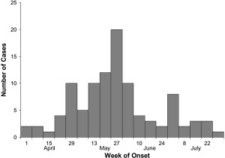

The figure below shows the epidemic curve, with cases surfacing around the beginning of April, peaking at the end of May, and ending by late July. Patients' age ranged widely, from age 30-90 (average--63 years).  And while they found that eating at the implicated restaurant greatly increased the odds of developing Brainerd diarrhea (89% of patients but only 14% of controls ate there, and it was the only stop for travelers passing through the county). Narrowing it down to a specific food or drink was a bit trickier, however; consumption of chicken, tomatoes, and tap water were associated with a higher risk, while drinking iced tea was protective. (They note that boiled tap water was used to make the tea, and ice was purchased from elsewhere because the ice machine was broken). Only water and tomatoes were found to be significant risk factors in the multivariable analysis.

And while they found that eating at the implicated restaurant greatly increased the odds of developing Brainerd diarrhea (89% of patients but only 14% of controls ate there, and it was the only stop for travelers passing through the county). Narrowing it down to a specific food or drink was a bit trickier, however; consumption of chicken, tomatoes, and tap water were associated with a higher risk, while drinking iced tea was protective. (They note that boiled tap water was used to make the tea, and ice was purchased from elsewhere because the ice machine was broken). Only water and tomatoes were found to be significant risk factors in the multivariable analysis.

They tested samples both from patients and from the restaurant for a number of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and parasites known to cause diarrheal disease. Though a few were positive for various agents, none were consistently found in a large number of patients, arguing against a role for the pathogens as the cause of Brainerd diarrhea. They also mention that by microscopy, particles were detected that looked like viruses, but they were unable to identify the species.

The second paper describes a smaller outbreak (23 cases) associated with a restaurant in California in 1998-9. Their methods were quite similar, using 2 case-control studies to identify first the restaurant, and then specific food items within the restaurant, and also similarly, samples were taken from patients and the restaurant for testing. Here, they did find Campylobacter species in several patients, but it's unclear whether they play any role in the development of the illness or not. They found that the bacteria had different pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns, however (meaning they weren't clonal, and therefore, not likely to be from a common source), and the patients didn't improve after antibiotic treatment cleared the Campylobacter infection--suggesting that the bacteria weren't the cause of the diarrhea.

So, why blog about papers where, essentially, they didn't find much? This emphasizes again that there's so much we don't know--and it also underscores the importance of publishing papers with negative data. Though no one has identified the cause of this mysterious diarrhea, having the information out there about prior outbreaks may allow someone in the future to recognize another ongoing epidemic, and perhaps succeed in identifying the agent responsible where previous investigators had failed.

In fact, it's quite possible that organism may already be staring us in the face. Could one of the unidentified viruses mentioned be the cause of Brainerd diarrhea? Sure. Could it be due to some currently unidentified, antibiotic-resistant bacteria? Sure. Could it be something else they're not seeing, and that we're currently unable to culture routinely? (Say, like archaea?) Sure, again. One thing they don't mention is why it took them so long to publish these papers, and whether the molecular examinations were done recently or back in 1996-7 (or 98-9 for the second publication) when the outbreaks were new. Developments in microarray technologies (such as those that I've mentioned previously) may be able to pull something out that older techniques have missed. All in all, an interesting syndrome and an interesting medical mystery; how long it will remain so is anyone's guess.

References

Kimura et al. 2006. A Large Outbreak of Brainerd Diarrhea Associated with a Restaurant in the Red River Valley, Texas. Clin Infect Dis. 43:55-61. Link.

Vugia et al. 2006. A Restaurant-Associated Outbreak of Brainerd Diarrhea in California. Clin Infect Dis. 43:62-64. Link.

Images from http://www.minnesotabound.com/visit/Brainerd/Brainerd.jpg and http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/CID/journal/issues/v43n1/38440/fg1.jpg

This isn't the first time an infectious agent has taken a long time to be isolated / identified -- didn't legionairres disease take months to locate?

I'm reminded of the history of cat scratch fever. Piers Anthony described his bout with it in the early 1990s, commenting that samples of the fluid from his swollen arm (terminology?) came back "sterile as space samples". IIRC, the bacterium responsible was identified only a few years later, and it turned out it just needed blood in the culture medium to grow....

Tara, I assume you know more/correct details there, but the point is that some of these bugs are "invisible" only because of the assumptions or techniques of the people studying them....

Oh yeah -- your "mentioned previously" link is broken, it seems to be misformatted....

Indeed, and that was relatively quick by some standards. Take Whipple's disease, for instance. First identified in 1907, bacteria were seen via EM in the 1960s, but weren't identified until the early 1990s because the causative agent (Tropheryma whippelii) couldn't be cultured by routine means. (It was ID'd using molecular techniques).

Absolutely--case in point above. Traditional sampling and culture techniques didn't prove fruitful, but using 16sRNA methods, a bacterium was identified and molecular tests for diagnosis were developed. And thanks for the link correction...put in a : instead of a ".

For example, if it could be identified, and bottled, and if it has low mortality rates, perhaps it could be sold for weight loss.

Yes, that's attempted humor.

If the population of Brainerd truly = -13,000, that's gotta be the nastiest bug on the planet...