West Nile is spreading beyond birds, horses and humans. A squirrel has tested positive for the virus and hundreds more are showing the same symptoms

People are finding squirrels in their yards or parks that look like they've been injured because they aren't able to walk. In some cases they're disoriented, running around in circles or shaking. Now it's believed they're suffering from West Nile.

(More below...)

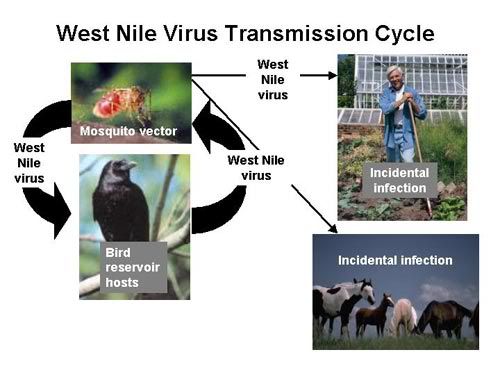

West Nile virus (WNV) is another arbovirus; that is, a virus that's transmitted by an arthropod (in this case, the mosquito). Typically, the virus cycles between birds (which are the reservoir species) and mosquitoes:

Humans and horses are species that are affected on a somewhat regular basis, but are considered "dead-end hosts;" we don't play a large role in the ecology and maintenance of the virus. Similarly, other mammals have been infected (such as raccoons, opossums, rats, and gray squirrels, as well as cats and dogs), but these infections appear to be infrequent. A large outbreak in squirrels hasn't been previously reported in the literature, though the CDC does touch on WNV infections in squirrels. In the news report, they note:

Dr. Richard Shackleford has never seen anything like this before. So after the first squirrels came in, he sent a blood sample to be tested for West Nile, and it came back positive. And he says the few hundred cases reported in the last month are only a small fraction of what's really out there.

So while it can't be confirmed that what's causing disease in all of these squirrels is actually WNV based on this report, at least one animal has tested positive for exposure to the virus, and the symptoms certainly are consistent with encephalitis caused by the virus.

The biggest public health threat, however, isn't from the squirrels themselves. When we carry out surveillance for the virus in nature, sentinel animals are used (often chickens) and tested repeatedly for the virus. Mosquito populations are also tested to see if any are carrying WNV. In this case, the squirrels can also be considered sentinel animals; the seemingly high proportion of WNV disease in that population suggests that there are a lot of infected mosquitoes in the area, putting humans at higher risk of being bitten by a mosquito carrying the virus:

"If we're seeing this many squirrels with it, that tells us a lot of mosquitos have it, and therefore the humans need to be much more aware of it and protecting themselves and their children," said Dr. Shackleford.

Image from http://www.dhpe.org/infect/Arbovirus.html

So basically, Tara, the "Squirrel Scene" in National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation is an accurate forcast of what we should do when faced with one of the varments...

SQUIRRELLLLLLL!!!!!

"Where's Cousin Eddie when you need him? - He usually eats these things!"

Hey Tara, thanks for posting and elaborating on this issue. I have a question for you. As a 28 year old living in one of the highly infected areas of Boise, should this be something of concern for me? I am curious, should those not in an at risk demographic try to protect themselves? In my own naivety wouldn't you acquire the necessary antibodies to prevent it from wrecking havoc in later years?

J-Dog--heh. I doubt they'll be attacking anyone in their state...

Mike, most people who develop serious clinical disease from West Nile are the old and young, or those who are otherwise immunocompromised. At 28 and assuming you're generally healthy, it's rather unlikely you'd become ill even if bitten by an infected mosquito, but obviously as someone who works in public health, prevention is always the best policy. If you're going to be out and exposed to mosquitoes, IMO putting on some bug spray can't hurt. I use it regularly--not because of disease, specifically, but because mosquitoes just seem to love me.

A few years ago, I wrote a story for New Scientist speculating about whether the similarities between West Nile virus and Polio (both attack the CNS) might extend beyond infection. Post-Polio Syndrome (PPS), which causes a suite of symptoms ranging from general fogginess to problems with coordination and movement, is a by-product of having been infected. Neurons near virus-killed neurons take over for their dead comrades. These hero neurons are why some of the children who were paralyzed seemed to recover so completely. But this extra workload leads to an accelerated die off of neurons decades later. That's PPS. A lot of PPS patients, however, actually had a non-paralytic form a polio, the symptoms of which were described as flu-like -- suspiciously similar to West Nile Fever.

Anyway, one the WNV victims I interviewed was an older woman who lived in a poor neighborhood on Chicago's South side. A year later she was still kind of shaky. According to her daughter, the woman liked to sit on a lawn chair on the steps of her home on hot summer nights. That's probably where and when she was bit by an infected mosquito. Then the daughter added a little aside about sick squirrel that had been in the yard earlier that day. Apparently, the locals kids had been torturing it...

The year the woman was infected was the first year West Nile hit Chicago really hard. I remembered seeing squirrels acting oddly. They'd lay out on the sidewalk and just kind of stay there. I even saw a field mouse that could barely drag itself across a suburban patio in broad daylight, though it perfectly aware it was being wached.

I got in touch with a researcher at the Illnois Dept. of Natural Resources that I'd heard had been studying squirrels. Here's the abstract from the paper he was then working on: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=pubmed&cmd=Retrieve&do…

There was a lot of concern over squirrels at the DNR, but the samples sizes they had to work with were small. It's one thing to ask the public to submit dead birds, but you really can't ask them to go near a squirelly squirrel. Still, there was a sense that squirrels, if only as carrion, played a part in keeping the viral flame going in crows. It's also possible that squirrels, which like to chase and bite each other and curl up together at night, may have passed the virus squirrel to squirrel. So mosquitos might not be required in every case.

And as you point out, sick squirrels can certainly act as sentinels... And since I haven't seen any crows around my neck of the woods all summer, they may turn out to the sentinel of choice...

Janet,

That is very interesting I live in Chicago and I don't recall hearing about squirrels getting the virus but I do know about collecting the dead birds. I guess they kept the squirrel part quiet.

Hi Laura,

It wasn't so much that it was kept quiet. It was more of a disconnect between the Dept of Natural Resources and the Chicago Dept. of Public Health. I actually called the head Public Health person (I can't remember his name -- it was a while back) and asked about squirrels. But by that point they weren't even accepting dead birds, so squirrels weren't even on teh radar. They felt they had the information most relevant for their mission, namely that West Nile was in the area. Spray, spray, spray...

When half the ~30,000 birds that were tested for West Nile during the second year of the outbreak came up negative, Tracey McNamara, the veterinary pathologist at the Bronx Zoo who helped connect the dots leading to the original West Nile diagnosis in 1999, pointed out that they died of *something,* even suggesting avian influenza as a possibility. But funding was only for WN testing, so the birds, and any evidence of other circulating pathogens, were tossed in the dumpster.

This sort of thing is more the rule than the exception. It's simply much easier to get money for a disease de jour than it is for the low-glam work of building up baseline data.