As I mentioned Friday, the good folks from Google were part of the crowd at this year's ICEID. This included a talk by Larry Brilliant, described on his wikipedia page as "...medical doctor, epidemiologist, technologist, author and philanthropist, and the director of Google's philanthropic arm Google.org." His talk discussed not only stopping outbreaks in their tracks--as current outbreak investigations seek to do, and Brilliant himself as worked on, as part of his background in vaccination campaigns for polio and smallpox--but to pay attention to "the left of the epidemic curve" as part of Google's "Predict and Prevent" initiative. More on what that means after the jump.

As I mentioned Friday, the good folks from Google were part of the crowd at this year's ICEID. This included a talk by Larry Brilliant, described on his wikipedia page as "...medical doctor, epidemiologist, technologist, author and philanthropist, and the director of Google's philanthropic arm Google.org." His talk discussed not only stopping outbreaks in their tracks--as current outbreak investigations seek to do, and Brilliant himself as worked on, as part of his background in vaccination campaigns for polio and smallpox--but to pay attention to "the left of the epidemic curve" as part of Google's "Predict and Prevent" initiative. More on what that means after the jump.

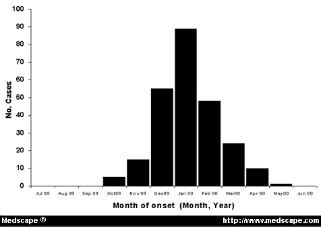

For those of you who may be unfamiliar with what an epidemic curve looks like, here's a generic example from Medscape:

Going from left to right, you'll have introduction of the pathogen into a population, amplification of those infected, eventually reaching a peak of cases, followed by a decrease in cases (due to loss of susceptibles, interventions put in place to stem the spread of disease, or other factors). What usually happens is that we find out about an ongoing outbreak at some point during that middle portion of the curve, typically when cases are increasing--sometimes over the course of days or weeks, other times over months or years. What we try to do, then, is figure out what happened in that left part of the curve. Who was the index case--the first person to be infected? How did they get infected? What's spreading the organism around through the population? The better we understand these, the more quickly and effectively we can work to stop the outbreak.

Brilliant suggested that the way we treat outbreaks is outdated, and we need a new paradigm for this century. We need to focus more on the far left side of the curve--getting better tests and notices for outbreaks when they're in their infancy, and identifying "hot spots" for potential outbreaks even before they start.* We've done so-so with predicting "what" will occur next--the lingering threat of antibiotic resistance, for example, or predictions years prior to SARS that we should pay attention to coronaviruses. However, we've not been nearly as good at the "when" and "where." Much of our efforts have been focused on early detection of and early response to outbreaks already in progress--is that all we can do?

Stopping infectious disease can be an outrageously large undertaking. Brilliant noted that during the smallpox campaign he participated in, more than 150,000 workers were involved, and they collectively paid more than 2 billion house visits. A better way than controlling after something is already out there in the population would be to stop it before it even begins.

How to do this, then? One way Brilliant suggested was "digital detection," using services such as ProMed to gather information on "outbreaks" when they're still limited to a few cases, or even a single case. We can also monitor sales of pharmaceuticals to find out where an unrecognized outbreak may be taking place. We need to make better use of multiple data sources in concert to know what's going on out there beyond what's being seen in hospitals and clinics. One Google-sponsored application in this genre is HealthMap, which brings together a number of sources (including Google News and ProMed, among others) to map disease activity.

Brilliant noted that we should pay attention to what people are looking for as well. For example, an uptick in people searching for certain terms or conditions could signify an unrecognized outbreak in progress, or be an early indicator of a coming epidemic.

As I've discussed previously, we can also use satellite data to examine drought, rainfall, etc. and link these to health outcomes, or map the distribution of disease vectors and relate these to climate conditions to get a better early warning for areas that may be prime locations for outbreaks.

What is essential for all of this to work, though, is timely sharing of data. Brilliant noted that this is impeded by the current academic model, where data can be locked away for months or years prior to publication--and some data is never published due to bias against negative studies or other types of information. He left open-ended his question regarding whether a different model of academic recognition, based on early sharing, would work. Color me skeptical--while I think it's a great idea, and perhaps with more moves toward open access it may work better in the future, but as things stand now it's just too much of a risk without enough incentive.

Brilliant also noted that none of this will work without the capacity on the ground. While it's ideal to pontificate about how great all this would work and the integration of all these different technologies, someone still has to generate a lot of that initial data--submitting case reports to ProMed, or searching the internet for symptoms, etc. Clearly that will be great in some areas and all but absent in others, so for this to really succeed the program needs to involve more than technology, and invest in personnel as well--and include forays into not only human and animal health, but larger environmental and cultural issues as well.

So, assuming all this could be done and we could get a better handle on that left side of the epidemic curve, and theoretically dramatically lessen or eliminate the big incidence peak, where would we then stand? Well, we still are left with the problem that, right now at least, we still don't often know why they emerge. It's a great "big" idea and one that could come to fruition with Google's backing, but it's certainly an uphill climb.

(*Yes, I know I've not blogged the recent paper on this very topic; I'll get to that after I'm through with the Atlanta post-conference blogging...)

Images from:

http://www.medscape.com/content/2002/00/42/35/423528/art-eid423528.fig3…

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/35/Larry_Brillian…

The February 21, 2008 issue of The Economist had an article about Nathan Wolfe's Global Virus Forecasting Initiative. (And there was an article in there about Brilliant back in January.)

Why hasn't simple rainfall forecasting been done to predict increases in the incidence of malaria? Early warning only helps if the response is rapid and effective. Even for a simple illness for malaria it is not.

Let me drop in for a moment - you have a good blog and you're discussing a piece of my daily work. Larry has a number of ideas within Predict and Prevent, and a small portion of them involve my organization, InSTEDD, founded by Google.org. Anyone likely to read this blog is probably interested in the ideas under development with us, and I'd welcome your thoughts about them, good, bad, and indifferent, and about anything else you find relevant. Contact me at Rasmussen@instedd.org, or drop out to the website at www.InSTEDD.org.

Re the comments above, Nathan Wolfe is a conversation in all of this, as is the Rapid Diagnostics work by Scot Layne, and Tracey McNamara's work on zoonotics, and the NASA-Goddard work on environmental forecasting. It's a really busy world out there around environmental modifiers in epidemiology, and some great work is unfolding internationally. Don't hesitate to point me to it. Everything we're doing at InSTEDD is free and open-source software, and early versions of some pieces are already posted. Some of the rest of our work is a socio-political effort and we're working with a range of people, including cultural anthropologists. Please critique what we're doing. Eric (Tara, thanks for the loan of the electrons...)