[This fall, I'm teaching a course at Emerson College called "Plagues and Pandemics." I'll be periodically posting the contents of my lectures and my experiences as a first time college instructor]

Lecture 1

That was a scene from Monty Python's Holy Grail, demonstrating the lighter side of the plague. Who knew there was a lighter side of plague? Of course the darker side is easier to envision. This is a graph showing estimated human population over the last millenium. That enormous dip during around 1350 is not a result of people having less babies - as much as 10-20% of the entire human population may have been wiped out in that decade in the mid 14th century by a tiny bacterium called Yersinia pestis. In this course, we're going to be talking about a lot of unpleasant things, from viruses that make you bleed from your eyes, to bacteria that give you such terrible diarrhea that you die from dehydration, to infectious diseases with the potential to wipe out humanity.

But we're also going to discuss some really great things like vaccines, turning viruses into antibiotics, and even sex. I realize that sex in the context of infectious disease doesn't sound like a pleasant topic, but I'm talking about a theory that suggests that the whole reason sex evolved in the first place was to help us evade infectious microorganisms. And of course, we're going to be discussing science itself, which is awesome.

Why is Science Awesome?

Principally, science is awesome because we are not. Our ability to perceive things is limited and flawed, our memories are limited and flawed, and our minds are filled with biases that distort reality even when the information is right in front of us. Science helps us overcome our own limitations (to the extent we are able).

Perception

Take a look at this image:

The squares marked "A" and "B" are actually the same shade of grey, but no matter how long you stare at it, you can't convince your brain of the truth.

This is the same image with the rest of the board covered in white.

We like to think that what we perceive is an accurate representation of the world, but it is just an interpretation of the world. Our brains have been wired by evolution to expect certain patterns - things that appear to be in shade are interpreted to have a lighter tone for instance - but when those patterns are violated, our brains end up distorting reality.

Our brains also have limited attention to devote to perception. In the following video, two teams (white and black), are passing a basketball between one another while moving around each other. Try just counting the number of passes made by the white team. You can't do it - there's too much else going on (don't read on until you've tried it).

Were you able to count the number of passes? Of course, that's not the real thing being tested - it's your ability to see something unexpected that you weren't paying attention to. In this study, about half of participants completely fail to see the gorilla walking through the middle of the players.

Besides being presented with a limited and often distorted view of the world, our recall of what we perceive also has serious flaws.

Memory

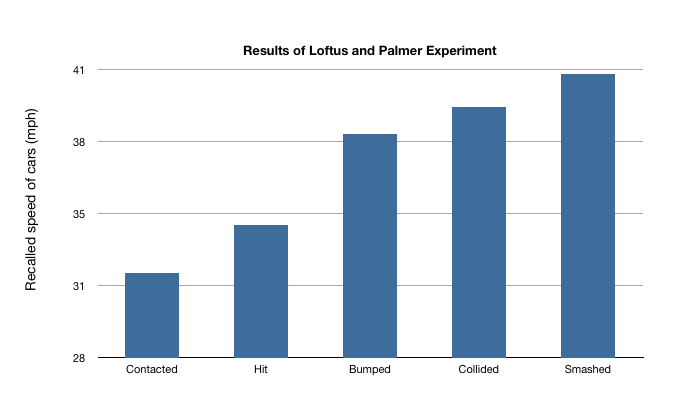

In 1974, psychologists Elizabeth Loftus and her mentor John Palmer showed test subjects a series of videos of car crashes, and then later asked to recall about how fast the cars were going at the time of the accident. But they weren't testing how well people could estimate speed, they were testing their own ability to subtly manipulate the participant's memory. The participants had been randomly assigned to 5 groups, and asked

About how fast were the cars going when they [contacted]?

But that final word varied - some participants were asked how fast the cars were going when they "hit," "bumped," "collided" or "smashed." The only thing that varied was that final word in the question, yet the memories of participants were dramatically different.

Further, participants were asked a week later whether they remembered seeing broken glass (there was no broken glass). If the participants had originally been asked how fast the cars were going when they "smashed," they were nearly 3 times as likely to remember seeing broken glass. In other words, the simple act of changing the word used to ask a question can have lasting impacts on people's memories.

Examples like this abound in the scientific literature. We like to believe that our memories are more or less carbon copies of our experiences, that we store memories away like files on a hard-drive, and that we can pull them up intact and unsullied. In fact, our memories are highly maleable, and are re-formed each time we access them. Scientists have shown that memories can be erased or invented out of whole-cloth. (For more, check out the Radiolab episode "Memory and Forgetting")

To top it all off, biases can insert, remove or alter the information in our memories at every stage of formation and retrieval.

Biases

Just check out the wikipedia page on cognitive bias, and you begin to grasp what fallible creatures we are. Just to name a few of my favorites - we tend to remember information that supports our beliefs and ignore what contradicts them (confirmation bias), we apply logic that will allow us to draw the conclusions we want to draw (motivated reasoning), and we believe that things that are correlated must be causally linked.

Science is awesome because it attempts an end-run around our failings by forcing us to be more systematic in our search for knowledge. We confront confirmation bias by intentionally trying to disprove our own hypotheses. We confront motivated reasoning by getting others with different motivations to vett our ideas and our results. We don't let correlation imply causation - we run experiments to test causal links.

Of course, science is done by humans, so it's not exactly perfect. But as Carl Sagan wrote in Demon Haunted World, science is "by far the most successful claim to knowledge accessible to humans."

If you're a scienceblogs reader, chances are this post hasn't told you anything you don't already know. My aim with this lecture was to give students who might not have the best relationship with science a different type of introduction. Science is so often taught as a fixed body of knowledge. "There's your biology textbook filled with facts, now go and learn those facts and repeat them back to me on a test." I wanted to give a sense of why we need science, and impress upon them that science is a process of discover, not a discrete set of information to be memorized.

Next up: Intro to evolution and basic biology.

"Science helps us overcome our own limitations "

So how come you needed a bunch of people with humanities degrees to tell you about the lighter side of the plague?

Fair enough - science helps us overcome our limitations with respect to understanding the objective physical world. If you need help with your subjective interpretation of the world, science can't help much.

(a) Looks great - I'd say those are some fortunate undergrads.

(b) I'm pleased to say I spotted the gorilla.

Re: (b) - Ok, maybe you need a more challenging task. Try watching this video, counting the number of passes of the white team, and try not to see the gorilla. You'll only be able to do it if you're paying very close attention - generally, if you expect to see something, you will.

It was interesting to see how much of your first lecture mirrors my own (including the video clips and references). You might be interested in this clip from Monty Python which highlights the dangers of the Scientific Method gone wrong (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zrzMhU_4m-g). My blog also engages in the interface between science and society (http://www.thebioguy.blogspot.com/) Enjoy.

What's that they say about great minds? You haven't put your intro lecture online have you? I'm pretty sure I came up with the structure on my own, though it's hard sometimes to know where you've cribbed your inspiration from (other times, not so hard - I'm stealing most of the intro for my next class from Bill Bryson's Short History of Nearly Everything).

Awesome! Great introduction with other perspective about science.

Hi Kevin,

Never posted my lecture (never thought to). My intro lectures for my Biology course involves Confirmational Bias and the Scientific Method. I also use a 3-2-1 Contact segment of Linus Pauling trying to determine the object inside a closed box. The Fire Breathing Dragon passage from Sagan's A Demon Haunted World is a good discussion starter as well. Good Luck!

A great lecture which actually answered the question I had asked a week ago very thoroughly. The whole science vs. humanities thing, or science vs. religion thing, or science vs. art thing, I've always had a bit of trouble with. I believe(believe clearly being the keyword here) that there are different types of intelligence and perhaps, different types of knowing. I've heard what some folks say about the limits of science, as well as the limits of faith or the limits of art and it seems that the critics of each group reflect the bias of their own affiliation. Originally my college education was in psych and soc. I admit this had a lot to do with a lack of good direction combined with a desire for some sort of education, anyway: I noticed that generally a psych theory reflected the time of the theorist as well as the personality of the theorist. Years after graduating college and having shifted in interest to med lab work/chemistry/biology(all that cool science stuff) I read the book, "Please Understand Me." Frankly, I know it isn't science, as it is difficult to really test and is self scored, but, that book, more than four years of undergrad psych work taught me that different people have different views and expectations as well as take comfort in different explanations and activities. Science is clearly the best way to discover, describe and understand physical reality. Humanities the best way to understand the human experience. And although I won't present an argument here, religion may be the best way to understand Humanities long term dreams and desires.(Yeah, I know, norse myth describes norse culture, greek myth greek culture, Roman myth roman culture, Celt myth Celtic culture etc, etc, etc) But, I believe it (religion) describes how we see ourselves in the big picture, what we see as perfection and how we should try to deal with our lack of perfection on a daily basis. Babble, babble, babble, babble....sorry, I'm off now!