Hello. I'm still here. Let me get you caught up on some things.

In graduate school I was required to take a battery of four qualifying exams before I could be “advanced to candidacy.” These exams were conducted orally, meaning you had to stand in a room with two faculty members and answer questions for as long as they cared to fire them at you. The exams were in Algebra, Analysis, Topology and a fourth area of the student's choosing, which in my case was Number Theory. These were very stressful, high-stakes exams that entailed many weeks of intense studying. I saved topology for last, since I regarded that as my weakest subject. As I walked out of the room after taking the exam, having been informed that I had passed, it suddenly dawned on me that that was the last math test I would ever take in my life. I would never again have to prove my basic competence in mathematics to people in power over me. It was quite a heady feeling.

Something like that happened at the end of this school year. You see, I was informed that I had been promoted to full professor. That was nice. It marks the last time I will ever have to put my work up for judgment to my colleagues, not, at least, for reasons having to do with my employment. Also, you get a nice raise. Reaching this milestone, at age forty-one, makes me reflect a bit on how I got here. The academic job market is such a crap shoot that I feel incredibly lucky not just to be employed, but to have wound up at a school that I love, in a nice area of the country, surrounded by terrific colleagues. As far as I'm concerned, I have the best job in the world.

That said, I'm also starting to understand why it is often said that research in mathematics is for the young. I have never been an especially enthusiastic researcher, and lately I've been finding my enthusiasm waning further. I love writing my books and I certainly have plenty of ideas I'd like to pursue. But the appeal of spending hours a day, for weeks at a time, trying to make significant progress on highly esoteric math problems is dimming somewhat. I do have a very enthusiastic long-term collaborator, though, and he helps make sure I keep one foot in the pool.

On the other hand, my interest in chess has been reawakened recently. Since I started graduate school in 1995, I have not really been a serious player. I have always subscribed to chess magazines, certainly, and just as a fan I followed the goings-on in the chess world. I played occasionally, especially at the team even in February. But it was nothing like when I was in high school, when I participated in an active chess club every week, looked for every tournament I could possible play in, and made a serious effort to improve my play. My rating has been bouncing around the high 1800s and low 1900s for twenty years. Frankly, during those years, math was providing for me what chess used to do. But watching the live broadcasts of the U. S. Chess Championship online really woke up the playing bug, and I decided I wanted to get back to the board.

So I did! I decided to play in the World Open chess tournament, which has recently moved to Arlington, VA after many years in Philadelphia. At nine rounds it is a long and grueling affair, spread out over five days. (Actually, you have your choice of several different schedules for playing the nine games, but let's not get into that.) And, for the first time in quite a few years, I decided to prepare seriously. For the past six weeks, such free time as I have had has been mostly dedicated to reading chess books, playing practice games at the internet chess club, and just generally trying to figure out how to play this game.

That, along with my recent general apathy toward world events, has largely led to my lack of blogging.

Well, the big tournament was this past weekend. Did my studying pay off? Let's find out!

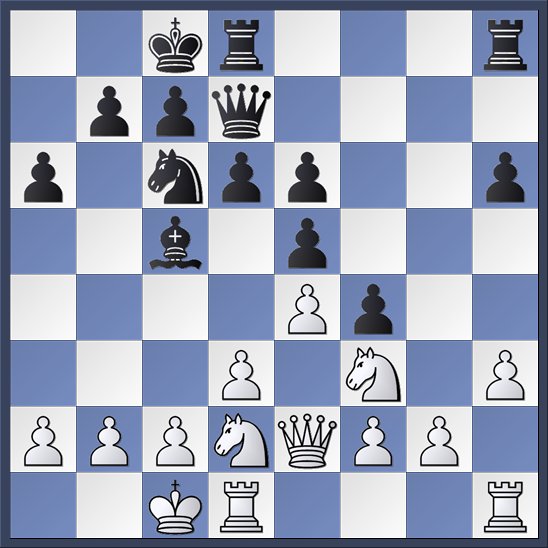

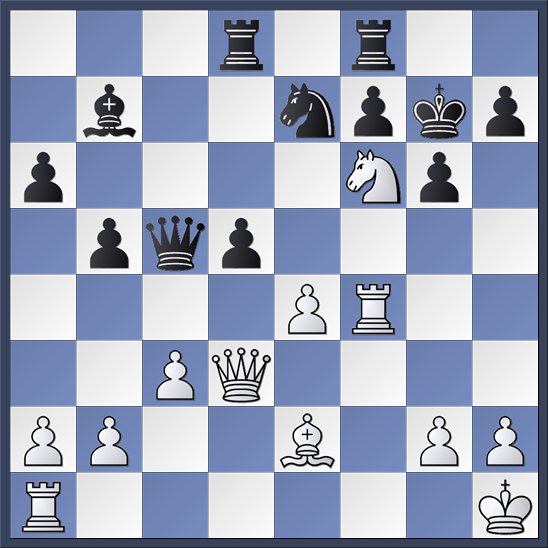

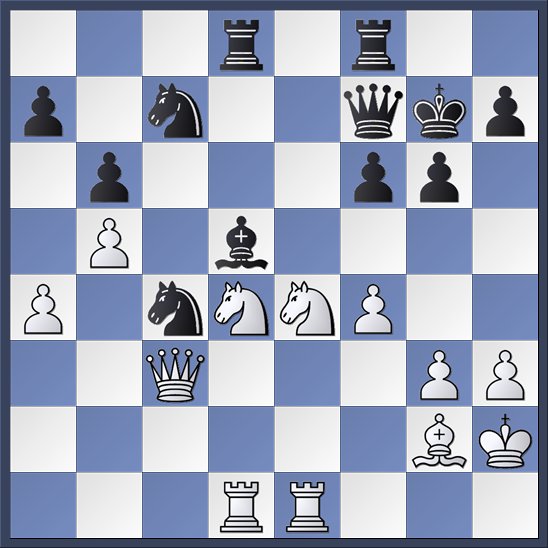

Round one was on Wednesday night. I was playing black, and the above position arose after black's fourteenth move. The opening was a Giucco Piano, which is Italian for "Quiet Game." This is a very old opening indeed, being one of the first to receive serious analytical attention from strong players.

Now, I happen to know that some of my chess friends read this blog, and they are probably a bit surprised to be seeing this. They know that for years I have been a loyal defender of the Scandinavian Defense. Indeed, I have. I have played many wonderful games with that particular opening. The trouble is that I have also lost quite a few games with it. There have been several recent books on the opening, and they have convinced me that if white knows what he is doing he has a couple of routes to a very good position. The opening has always existed on the periphery of master practice, and I was gradually coming around to the common view that it's a bit dubious.

So as part of my preparation I decided to work out a new opening repertoire. And after considering my options, I decided I would go with the double king pawn openings in response to 1. e4. This is not a decision to be made lightly. At the master level you can be certain that you will face the Ruy Lopez after 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6, but below the master level you are more likely to see white put his bishop on c4. Suddenly you have to be prepared for all sorts of insanity! Sacrifices on f7, sudden Ng5 moves, psychotic but often effective gambits, that sort of thing. Happily, though, I had prepared pretty carefully, and I was actually glad to be able to give things a try in the very first round.

So back to the position. The Giucco Piano is not thought to give black any trouble, but surely white can do better than the above position! Black is doing very well indeed, with a strong center, open g-file, reasonable development and a safe king. White, for his part, hadn't been doing much of anything. But here he played a real howler with 15. Nh2. This was one retreating move too many. I guess he was dreaming about unleashing his queen on my kingside, supported by an eventual Ng4. Alas, dreams must yield to reality, and white has just left d4 unguarded. Play continued 15. ... Nd4 16. Qf1 Qa4:

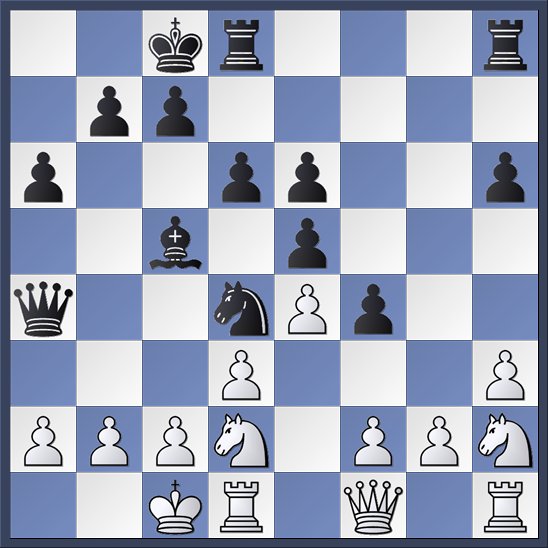

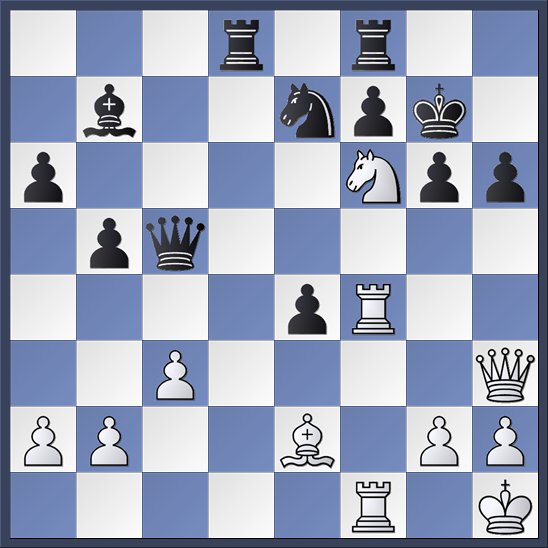

What a difference two moves make! White is busted, since he is about to lose either the a2 or c2 pawn. Moreover, he will almost certainly have to cough up a second pawn just to keep from being mated. For example, if I take with the queen on c2, he will probably have to move his knight from d2, but then his f-pawn will drop thanks to the combined activities of the black queen and bishop.

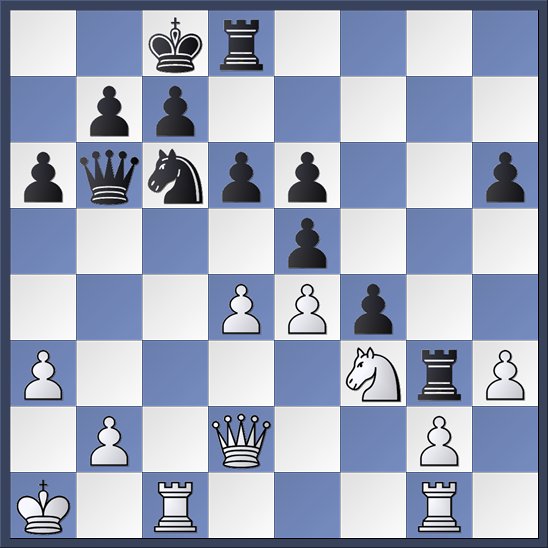

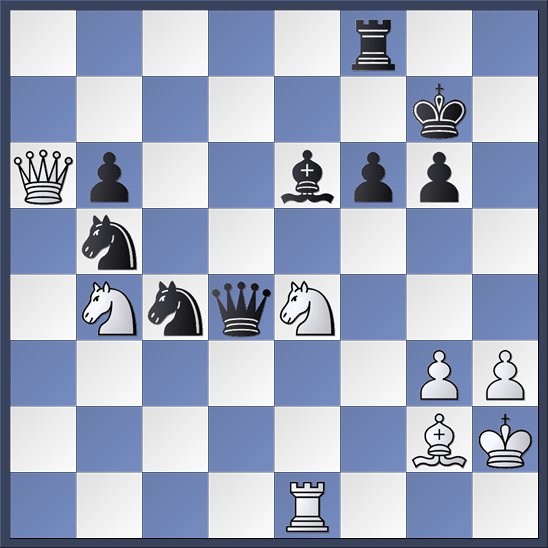

Let's fast-forward a bit. Black is about to make his 27th move:

He is still nursing his two-pawn advantage. That would become three pawns after the simple 27. ... Nxd4, but I managed to scare myself by seeing lines like 28. Nxd4 Qxd4 29. Qa5 (threatening mate on c7!) Rd7 30. Rgd1 Qf2 31. Rxd6! Yikes! That's more activity than white deserved. Actually, that line's total nonsense. Black's actually still winning at the end of it, and I could have played 29. ... c6 or 30. ... Qe3 instead, when all would have been well. But still. So I decided to go with the flashy 27. ... Rxf3. After 28. gxf3 Nxd4:

a knight fork on b3 or f3 will regain the exchange. Play continued 29. Qg2 Nb3+ 30. Kb1 Nxc1 31. Rxc1 d5! White's active queen will allow him to get one pawn back, but the eventual outcome is hardly in doubt. White resigned on the forty-fourth move. Score one for me!

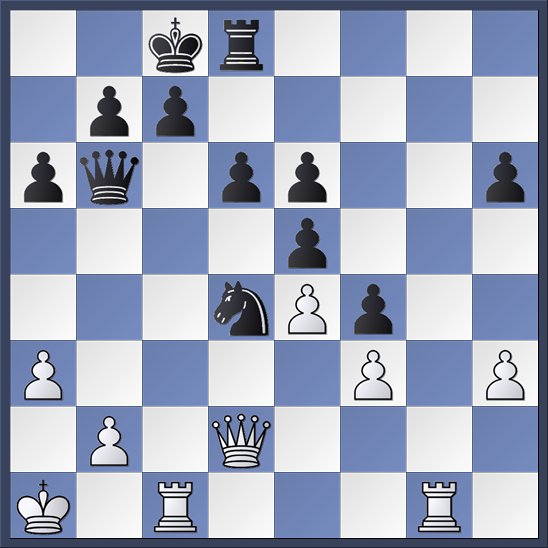

After that first round, you have to play two games a day. In round two I was playing white, and this position arose with white about to play his 23rd move.

This time the opening was a Sveshnikov Sicilian. White doesn't usually end up with a strong knight on f6 in this line, so something has gone wrong for black. The computer now points out that 23. e5! is winning for white. I suspect most masters would have played this move very quickly, and I certainly considered it for quite some time. But in the end I rejected it, preferring 23. Qh3. This, I think, points to one of the clear weaknesses in my play.

You see, sitting at the board as white in this position you notice that you have quite a strong king-side attack. The knight on f6 is a beast. It is well-supported by the rook on f4, and the other rook is about to swing over to f1. The queen goes to h3, and the bishop can appear on g4 to challenge the black bishop if it retreats to c8. This is all very promising. Looking at all that you want to get on with it. You want to make threats. You want to make progress. You want to attack!

The trouble is that black actually does have a source of counterplay. He will take the pawn on e4, which will dramatically increase the scope of his bishop and open the d-file for the rook. The move 23. e5 shuts down this counterplay and cements the knight on f6. White's attack is still there. Such a move requires patience, however, and I often seem to lack that in my games.

Play continued 23. ... h6 24. Raf1 dxe4:

And here I must share with you a terrible tragedy. I had reached this position in my analysis before playing Qh3. I now thought I was about to win the game with 25. Qxh6+! After 25. ... Kxh6 26. Rh4+, black needs a move. If he plays 26. ... Kg7 then 27. Rh7 mate follows. After 26. ... Kg5 we get the even cooler 27. Nh7+ Kxh4 28. Rf4 mate:

Pretty sweet, don't you think? But perhaps you have noticed the fly in the ointment. After 26. Rh4+ black just gives back the queen with 26. ... Qh5. Party's over. Capturing the queen will cost white a piece, and the game.

But it actually gets worse. Doesn't white have another appetizing move in this position? Doesn't 25. Nd7 just win an exchange? Indeed it does, and in a blitz game I would surely have played this immediately. The computer rates it as white's best. But I made the mistake of thinking about it first. I noticed that after something like 25. Nd7 Rxd7 26. Qxd7 Bc6 27. Qd2 f5 black is actually doing very well. Yes, he has lost a small amount of material. But his pieces are now active and he has a strong center. My rooks, meanwhile, are doing nothing and don't have especially bright prospects.

So what happened? I played the awful 25. Ng4, and after black replied 25. ... Ng8 white has no attack to speak of. I played a few more bad moves and resigned on move thirty-seven. Drat! After the game my opponent told me he had not even considered the queen sac on h6. Then he asked me why I didn't just win the exchange with Nd7. Good question.

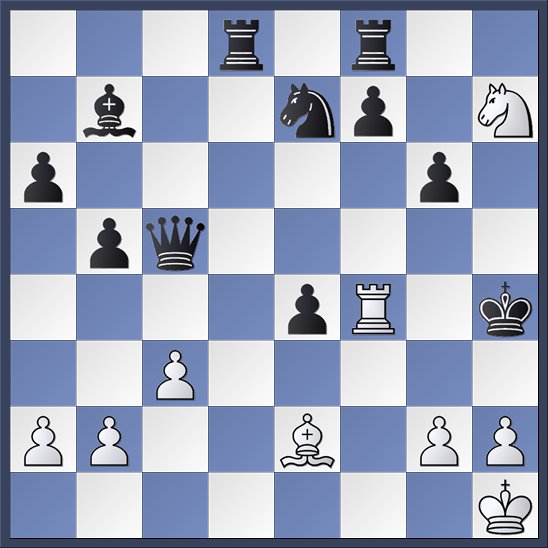

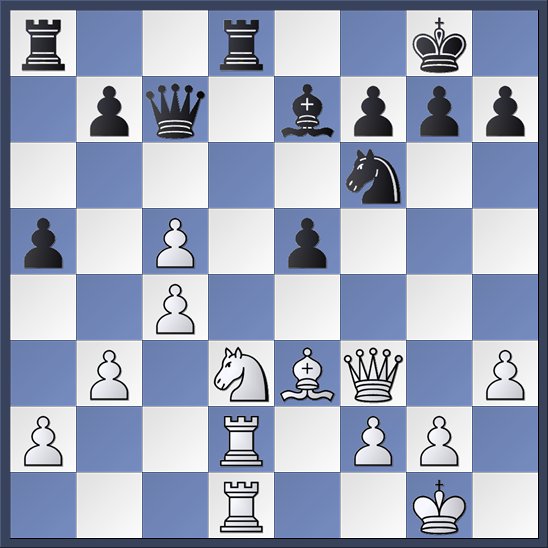

But things were about to get worse. Here's what happened in round three:

I was black again. This came out of a Reti Opening. It was really quite an appalling game by both of us. It was a good illustration of the maxim that the winner of the game is the one who makes the next to last blunder. In this case, that was me. Have a look at the position. It's pretty chaotic! But white's rooks certainly make a good impression. Come to think of it, so do his other pieces. Had he now found the simple shot 26. Nxf6! we both could have gone home early. Black is just all kinds of screwed after this move. After 26. ... Rxf6 27. Rxe5 white has just won a pawn with an overwhelming position. And 26. ... Kxf6 27. Nc6, among other possibilities, is hardly an improvement.

But white played 26. f4 instead. After 26. ... Nc4 27. Qc3 Qf7:

the move 28. Ng5 is a clean kill. This time the point is that black just gets mated after 28. ... fxg5 29. Nf5+ Kg8 30. Nh6 mate. After 28. ... Qg8 29. Re7+ wins the knight on c7 (at least), and after 28. ... Qd7 29. Bxd5 black has no acceptable way of recapturing. Seriously, after 28. Ng5 the computer's assessment is +12 for white.

And I never even looked at it. The move never even crossed my mind. I was just sitting there, calculating away, looking at all sorts of silly lines, and I never even saw these obvious tricks. It gets even more pathetic when you realize that this particular tactic was actually sitting on the board for several more moves.

My opponent missed it too. He did something entirely different and managed to blunder a pawn on the queenside. Here's the position with black about to make his thirty-sixth move:

The tide has certainly turned. And had I noticed that 36. ... Bxh3! is quite a nice shot, the game would have had a happier ending. The main point is that after 37. Bxh3 Qb2+ black is going to pick up the knight on b4, and he has just pocketed another pawn. Taking with the king leads to mate in four: 37. Kxh3 Rh8+ 38. Kg4 Ne5+ 39. Kf4 g5+ 40. Kf5 Qd7 mate.

How could I miss that? His knight on b4 is hanging for heaven's sake, so of course I should have been looking for ways to take advantage of it. My own bishop is also hanging, so I should have been looking for ways to address that fact. And in the moves leading up to this position I had been specifically thinking about swinging my rook to h8 at some moment. But somehow, when the opportunity arose, I managed not to put the pieces together (no pun intended). It's really very frustrating.

I even managed to make several more blunders as the game continued and lost. By the time I resigned about ninety minutes later I didn't even care any more. I just wanted to slink back to my hotel room and never play chess again.

What happened in round four the following morning did not exactly raise my spirits.

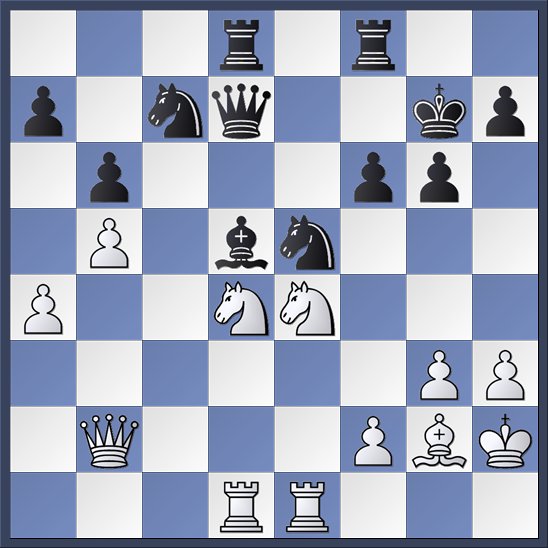

I was white. Here's the position as I'm about to make my twenty-third move:

This came out of the somewhat obscure Fort Knox Variation of the French Defense. The game began 1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 dxe4 4. Nxe4 Bd7 5. Nf3 Bc6. Black's idea is that his white-squared bishop is always a problem piece in the French, so he is willing to spend several moves to get rid of it. White will end up with a space advantage and a lead in development, but black's position is incredibly solid.

At any rate, have a look at that position. White's doing rather well, don't you think? He is up a pawn, thanks to a questionable gambit by black. His pieces are quite well-placed, and black has a weak e-pawn. With something like 23. Qf5, white can feel very confident about the future.

But I didn't play 23. Qf5. I got nervous about a subsequent g6 by black, after which I just have to retreat my queen. Besides, doesn't white have another way to attack black's e-pawn? I played 23. Qg3.

And it didn't take black long to bang out 23. ... Ne4, forking my queen and rook. Bruh-ther!

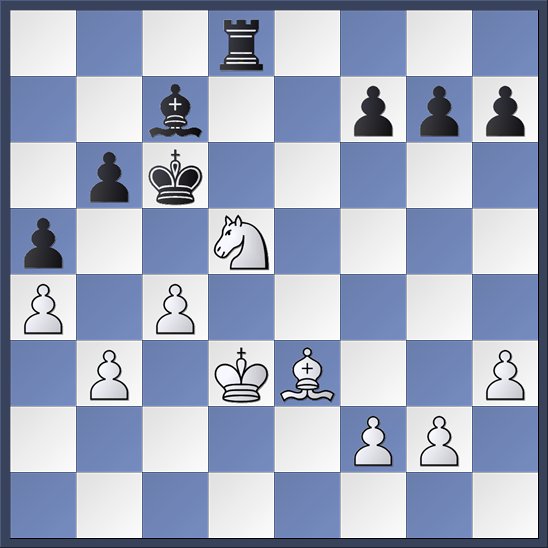

That's embarrassing. As it happens, though, the situation was not yet hopeless. Skipping ahead to move thirty-seven we find this:

White has certainly achieved all he could hope for. His knight on d5 is headed for the knight hall of fame, and black's b6 pawn is a terrible weakness. The computer confirms that black now has only a small advantage. My opponent had been moving very quickly after winning the exchange, and I think he thought the position would win itself. He certainly did not have to allow me to craft such a strong position.

Still, I expected him to torture me for a while. He could try slowly pushing his kingside pawns, for example, perhaps going for a position where he could just sacrifice his b6 pawn in return for rushing his pieces over to the kingside. I don't know if such a plan would work, but I do know that it's a lot easier for black to make moves than it is for white.

Happily for me, my opponent was feeling unambitious and offered a draw. I accepted, of course.

So, with four rounds down I was at one win, two losses and one draw. Both losses were from winning positions, and the draw was a lucky save, from a position that had once been much better. It was really all very discouraging. What was the point of doing all this studying when I was constantly blundering, or making crass analytical lapses, at the game's critical moments? Maybe tournament play was just too difficult. Maybe I should stick to composing chess problems, and leave playing to the players.

Well, maybe. But as it happened, the tournament was just getting started...

Jason: This was very instructive and entertaining! Certainly I have not played at this level perhaps ever, though I can sympathize with making less than optimal moves at the World Open. After some eleven forays at that brutal tournament, the first in 1985, and the last in 2008, when for a all-too-brief scintillating moment I was tied for second during the 5th round in the under 1600 section, I have never had ANY success! I like to think that I have provided many contributing dollars to the prize funds of the higher rated sections for over 20 years!

Anyway, I offer many thanks for this, especially as it seems that the World Open website has been down for over 48 hours. I was following the tournament quite closely, and find it very mystifying. I wish you much success with your return to serious chess. I know how rigorous the World Open can be, and if I may very humbly offer a much better player some cogent advice, it would be to say take at least 6 months to a year to prepare for such a monster. At it is, none of us is getting younger, and these new youngsters are far better prepared now than 30-40 years ago!

Again, this was excellent writing and analysis. Thank you!

Sincerely,

Thomas F. Hamilton

a lifer category II player

You’re forty-one? How can that be? You can’t be that old! If you were 41, I’d have to be… oh, wait… Never mind.

Thomas--

Thanks for the encouragement! I'm glad you liked the post. Your advice about needing more time to prepare is well-taken. I think actual playing is important too. As with anything else, there is a big difference between theory and practice. I guess I'll start working now for my go at things next year.

Jonathan--

Yes, Brown was quite a long time ago! I find it hard to believe too, but there it is. My students seem to get younger every year, and my cultural references become more obscure to them.

Good Point, Jason! Yes, my coach has always told me, in a wonderful way, that my big enthusiasm to tackle the World Open had to be judiciously tempered with study AND play in "smaller tournaments". If we all could just learn the perfect combination of such play and study, we'd certainly be more of a threat to take home the big prizes. Please continue to carry on with your excellent chess blogs. I especially liked one from the archives on a John Rice Chess Problem. Pure delight!

Thanks again,

Tom

"So as part of my preparation I decided to work out a new opening repertoire."

That's a good reason for not blogging indeed. Some eight years ago I switched from 1.e4 to 1.d4 and be sure my repertoire still has holes.

Hat tip from an experienced attacking player (not me, but the great Rudolf Spielmann): attacks against the king only have a chance of succeeding when there are more attacking pieces than defenders. And the defending king also counts. In the position where you played 23.Qh3 you don't have a majority of attacking pieces. In such positions the correct strategy is to get more pieces involved. Note that pawns also count, hence 23.e5 is positionally superior.

So next time you think you can decide a game with a direct attack count pieces first - the relevant ones on the board.

Btw I agree that Black gets good compensation for the exchange after 25.Nd7. That's even more reason to conclude that 23.Qh3 is inferior.

Have you done tactical exercises during your preparation? Most experts agree that it must be an integral part, preferably without a board.

MNb--

Yeah, tactics have always been a weak spot for me. Just wait until round eight to see a really misplayed attack. Relative to other people with my rating, I think I'm a little better at endgames and a little weaker in openings and tactics. The games from this tournament bear that out pretty clearly.

Of course, relative to grandmasters every aspect of my game is pretty weak.