All my hard work in Baltimore, and all the frustrations of the various drives, paled to insignificance upon arriving at the Parsippany Hilton. You see, it was time for another go at the U. S. Amateur Team East chess tournament. It's one of the biggest chess parties of the year, with more than 1300 players in attendance.

Me and my homies got together for one more run at the title:

Closest to the camera is our board four, lawyer-extraordinaire Brian Cige, sporting a rating of 1315. I never got around to asking him what his knight was doing on h5 here. Next to him is Ned Walthall, rated 1390. Ned got us all together in the first place by creating the Princeton Chess Club back in the late 1980s. He is also a photography enthusiast (check out his blog!). Since he was our team captain, you can understand our team name--Chess Aperture. It took me a while to realize that “aperture” was another word for “opening.” The fellow next to him in a contemplative mood is Curt Kimbler, sporting a rating of 1770. Knowing Curt, he was probably thinking about fishing while he waited for his opponent to show up. And the empty space next to him was where I was sitting. My rating has been bouncing up and down the 1900s for about twenty years now, and was 1917 before the tournament. This picture was taken at the start of round two, which ended up being a very exciting game indeed. Stay tuned.

As happy as I was to see everyone again, this represented a small change in line-up from past years. My friend Doug Proll did not play this year. His warped priorities involved him spending Valentine's Day with his girlfriend, so we didn't get to see him this year. What's wrong with people?

Before getting to the chess, let's review how this works. This was a team tournament. In each round the four of us played four individual games of chess, with no communication between us. For each game we won our team got one point. A draw counts for half, while a loss gets you nothing. When all four games are finished, the team with the most points wins. As far as the tournament is concerned, it does not matter whether you win 4-0 or 2.5-1.5. All that matters is who wins the match (of course, drawn matches are possible too). That's what makes it a team tournament.

This is the “Amateur” team tournament. That means the average rating of the four players must be below 2200 (for an individual player, a rating of 2200 earns you the title of master.) Not a problem in our case! The top teams will tend to have average ratings of 2199. All the teams play in one big section, meaning you might be playing a team of killers in one round, and then a team of little kids in the next. On the other hand, with no cash prizes, a low entry fee, and nothing really but bragging rights on the line, everyone tends to be pretty mellow. That's what makes this such a fun tournament.

Let's get to the chess. In the first round we were paired way down. My opponent was sporting a 1500 rating. But however low-rated your opponent is, you still have to take care of business at the board. I've lost to lower-rated players than this kid, so I was taking the game very seriously.

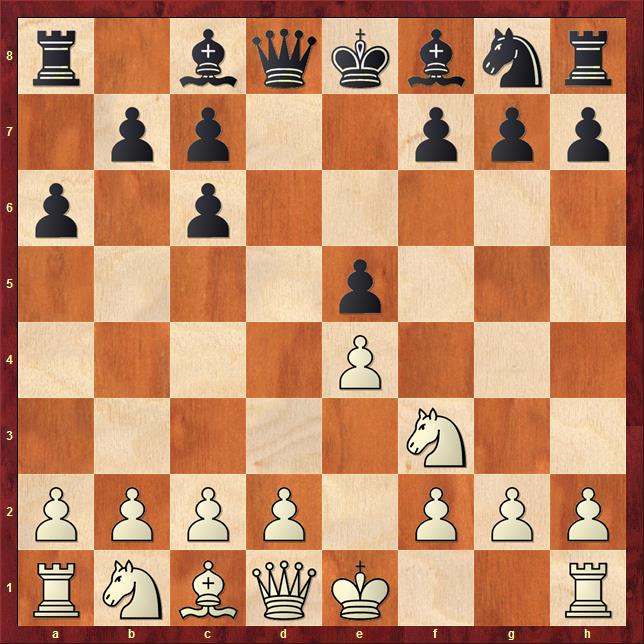

I was black. My opponent opened with 1. e4. Now, I'm sure you remember my epic three-part series on last year's World Open (Part One, Part Two, Part Three.) There I mentioned that I had recently abandoned my long-time favorite Scandinavian Defense and had started playing double king pawn instead. I stuck with that here. Four moves later we had reached the starting position of the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez:

White has traded off his light-squared bishop for a black knight on c6. Just four moves in, the basic strategic fight that will govern the remaining play is clear. White has damaged black's pawn structure and has a slightly stronger center. In return, black has the advantage of the two bishops. It's all very subtle stuff, but the general feeling is that black should be fine. This line is a rare visitor in grandmaster practice. On the other hand, Bobby Fischer liked to play this line with white, and he won some good games with it. But he had superpowers, so that doesn't count.

Everything proceeded normally for a while. Here's the position with white about to play his thirteenth move:

Here white started on a bad plan. He played 13. d4. Expanding in the center is often a good idea for white in these openings, but not here. In one fell swoop he is allowing me to get rid of my weak pawn and he is opening up the position for my bishops. What does white gain to make up for this? Nothing, that's what.

Play continued 13. ... cxd4 14. cxd4 exd4 15. Bxd4 c5 16. e5 fxe5 17. Bxe5 Qc6 18. Qc2, leading to this position:

Black would now win quickly with the flashy 18. ... Rxf3. Black invests a small amount of material to bust up white's kingside. Soon all of black's pieces will swarm to that part of the board, and white's king will not long survive.

I saw this possibility, but I went for the “safer” 18. ... Bxh3. This should have been a blunder after 19. Nf4. I had intended 19. ... Bxg2, of course, but after 20. Qc4+ Kh8 21. Bxg7+ black also has a busted up kingside, and it's white's move. Having the computer point this out to me after the game reminded me of a line I once heard from GM Roman Dzindzichashvili. In a lecture he responded to a bad move suggested by an audience member by saying, “If you make this move I will remind you there are two kings on the board and one of them is yours!”

Luckily for me, my opponent looked a bit dejected at this point. Play continued 19. Qc4+ Kh8 20. gxh3 Qxf3:

and my opponent resigned. A win is a win, but I wasn't feeling very good about my play.

That all changed in round two! Our reward for taking care of business so efficiently in round one (we won 4-0) was to be paired way up in round two. We were in for a tough slog, since we were substantially out-rated on every board. My opponent was a master. Here's what happened.

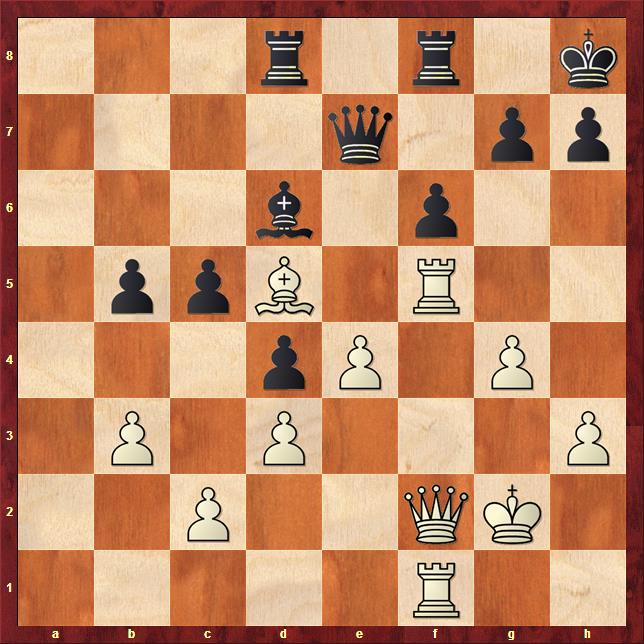

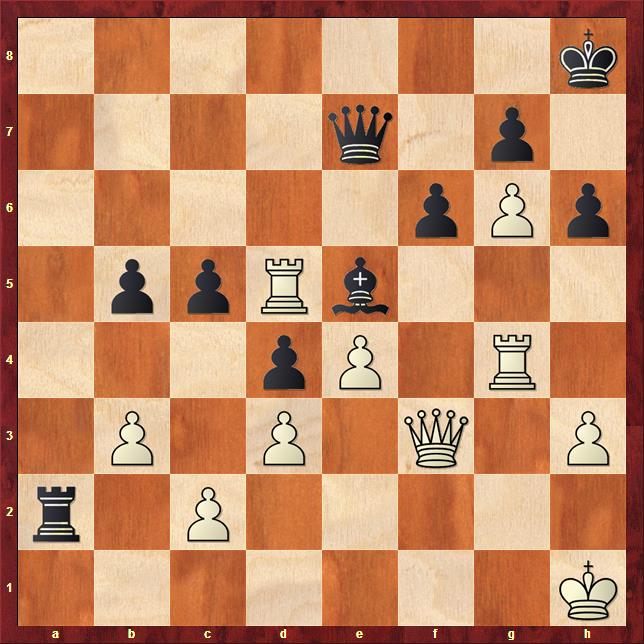

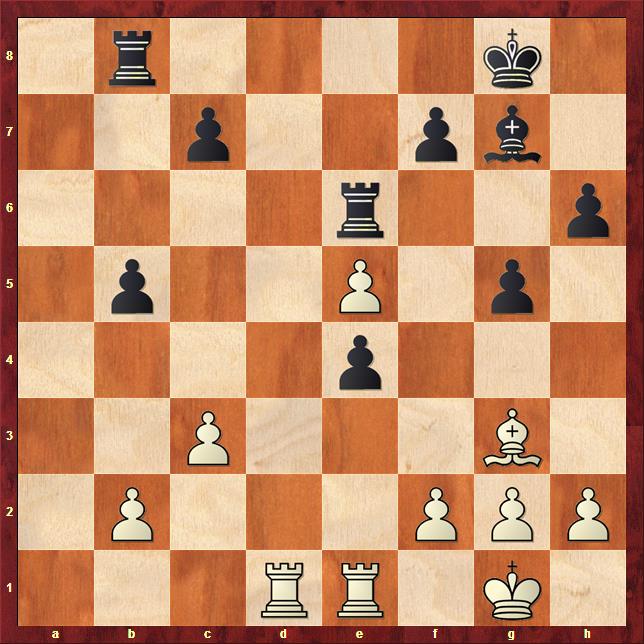

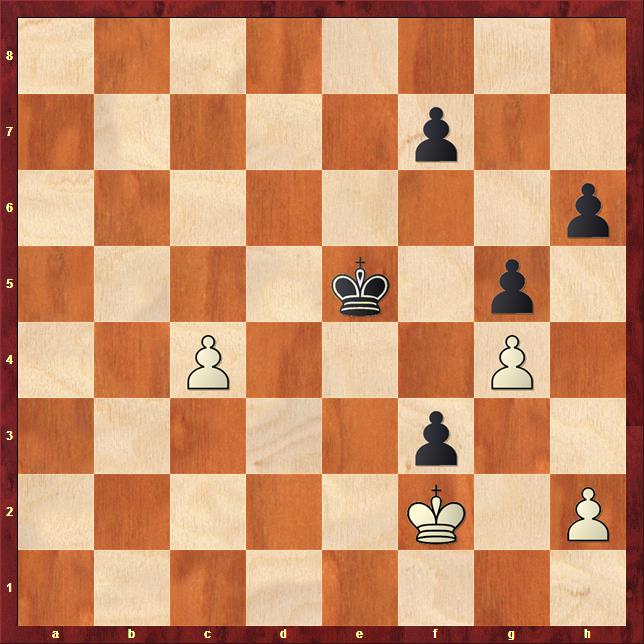

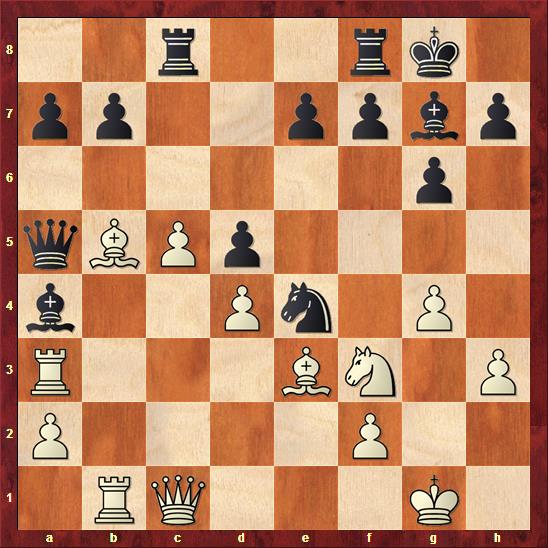

I had white. I played the Bishop's opening in response to 1. e4 e5. Play was pretty quiet, but I was happy with how the opening went. After white's twenty-seventh move we reached this position:

It looks pretty good for me, I think. My bishop on d5 is a beast, I have more space, and my heavy pieces look very impressive on the f-file. Not bad! But how is white to make progress? The bishops of opposite color make it possible for black to set up an effective blockade on the dark squares. White's only pawn lever is to move his pawn to g5. The trouble is that black will just take, since he has f8 adequately covered. All the heavy pieces will come off, leaving white with nothing. Also, white does have a weakness: the dark squares around his king. If I try diverting pieces over to the queenside to invade down the a-file, black will play moves like Bb8 and Qc7, when black will remind me that there are two kings on the board and one of them is mine.

So I felt like black could shuffle his d-rook on the back rank and white had no way forward. Indeed, the computer confirms that the position is only very slightly better for white. On the other hand, black has no sources of active play either.

So I made the waiting move 27. Kg2 and offered a draw. That's when things got interesting. He thought for a few minutes and played 27. ... Bc7.

I was shocked! I was sure he would accept the draw immediately and thank me for it. I was reminded of another story about GM Dzindzichashvili. In a late-round of the U.S. Championship, he sat down to play IM Kamran Shirazi. Shirazi had been having a terrible tournament, and had lost all of his games to that point. Dzindzichashvili, however, was in a non-combative and had been offering quick draws to near everyone. He did likewise in this round, offering an early draw. Shirazi mulled it over for a few minutes, but Dzindzi interrupted his thoughts. He said, “If you don't accept this draw then I will beat you too!” Shirazi accepted the draw.

That was essentially my reaction. How dare he not accept my generous draw offer! Now I will beat him, big rating or not.

And I suddenly had hope of doing that, since his last move was not very good. It is not losing by itself, but the computer evaluation suddenly jumps in my favor. The problem is that by diverting his bishop to c7, black has left f8 insufficiently protected. That means white's 28. g5 is suddenly effective. Play continued 28. ... Qd6 29. Kg1 Rd7 30. Qg2 Bd8 31. g6 h6:

Black has spent the last few moves wrong-footing his pieces. For his troubles he now has one of the weakest back ranks in the history of back ranks. His king is never--never-- leaving that corner. And if white were ever to get one of his heavy pieces to the back rank, things would get ugly for black. (Literary types call that foreshadowing.)

The next dramatic moment came after the moves 32. Qh2 Qb6 33. Qd2 Qb8 34. R1f3 Be7:

After 35. Rh5 Black faces a horrifying rook sacrifice on h6. His only defense is to sacrifice the exchange with 35. ... Rxd5 36. Rxd5. Play continued 36. ... Qe8 37. Rg3 Bd6 38. Rg4 Be5. White can win the pawn on c5 now, but I was worried that black might get some kind of counterplay with f5. I decided that maintaining the bind was more important than grabbing pawns. With his extra material and black's awful back rank, white's already winning. No need to get greedy.

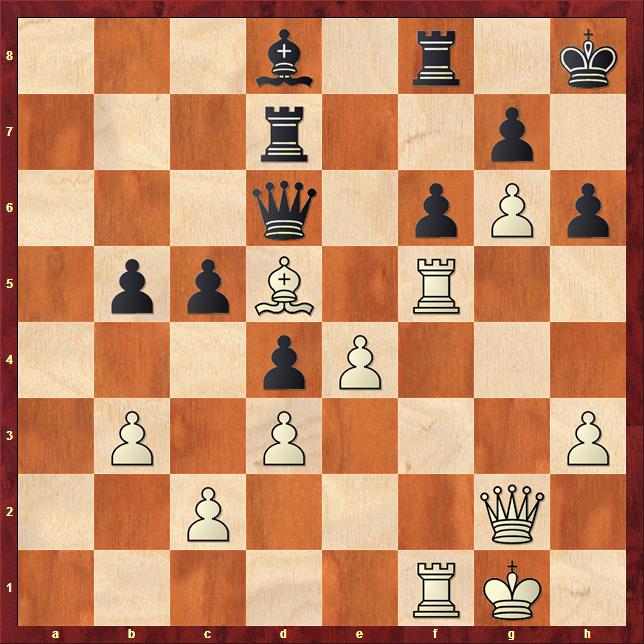

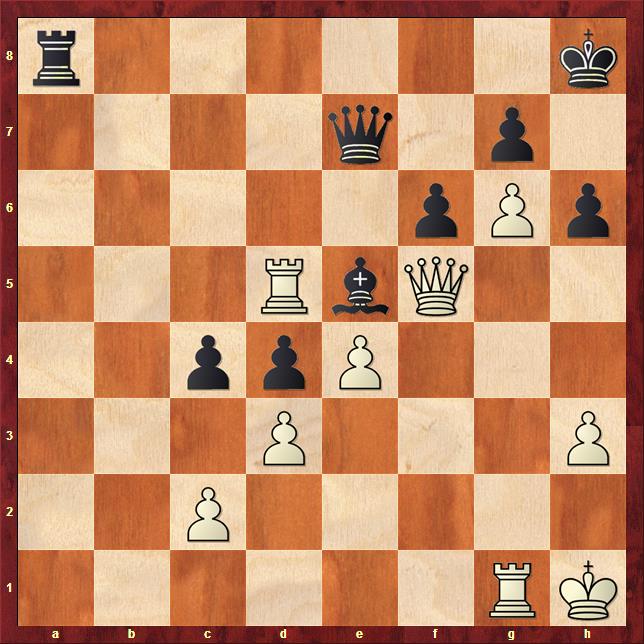

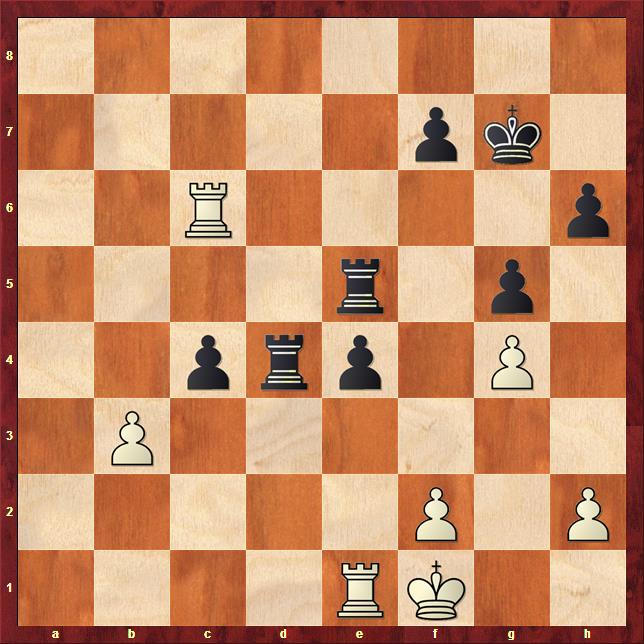

Let's fast forward a bit:

Black is doing his best to get active, by sending his rook to a2 and threatening white's pawn on c2. But this leads nowhere after 42. Qf5! The queen is threatening to invade on c8, which forces black to bring his rook right back with 42. ... Ra8.

At this point white has a couple of options. I considered playing the simple 43. Qd7, which forces a trade of queens, kills any possibility of counterplay for black, and leads to an easily winning endgame. The computer confirms that this is the cleanest win. The tempting 43. Rd7 seems less strong, however, since after 43. ... Qe8 white lacks a clear follow-up. In the end, though, I went with 43. Rg1. I figured the rook on g4 was my only bad piece, so I would try to bring it over to the queenside. Moves like Qd7 would still be there down the line.

Black tried to trade off pawns on the queenside. When you're down material the rule of thumb is to trade pawns but not pieces. In this case, though, black is just opening the queenside to white's benefit. After 43. ... c4 44. bxc4 bxc4:

White has the flashy 45. Ra5!. It's the weak back rank again. If black takes the rook he just gets mated by Qc8. The buzzkill computer likes this move, but points out that Qd7 was still better. The problem is that with something craven like 45. ... Rg8 black can hang on for a while.

But such moves are just too passive for humans. Play continued 45. ... Rb8 46. Rga1 Qb7 47. Ra7 Qb2 48. Ra8 cxd3:

Black's last allows white to finish in style. I played 49. Qc8+. My opponent muttered, “that's pretty convincing,” and immediately resigned. The point is that it's mate after 49. ... Rxc8 50. Rxc8 mate.

I was feeling real good about myself after that one!

The old Princeton Chess Club was well represented. Here are some more old friends:

The camera-shy fellow closest to the camera is Derrick Higgins, who recently moved to Chicago. No one misses the USATE, though, even if it means getting on a plane! Next to him is Jon Edwards. When I was in high school and started attending the Princeton Chess Club, he taught me much of what I know about playing chess. He is the former U.S. Correspondence Chess Champion, and has lately been churning out the chess books. Next to him is Joel Heinrich, a physicist who recently retired from a career at the University of Pennsylvania. Alas, their fourth board, Matt Allman, had already finished his game when I showed up to snap this picture. Fear not! He will turn up soon enough.

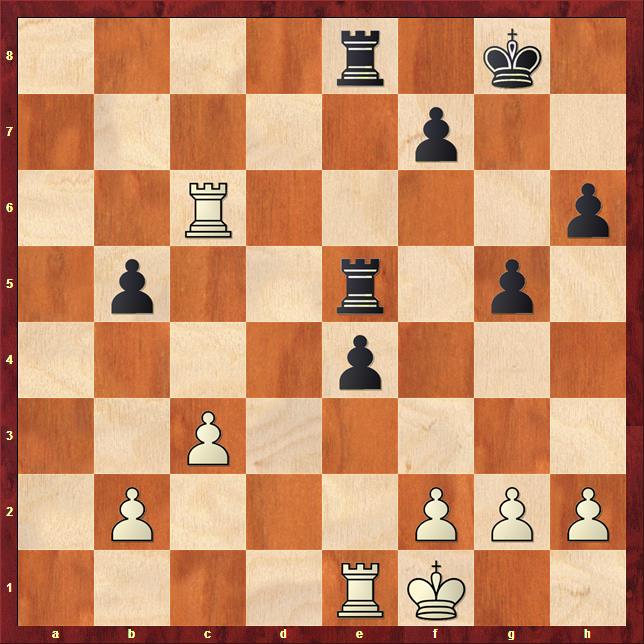

Round two went better than the ratings would have predicted. In addition to my win, Brian managed a draw on board four. We still lost the match, though. This did not save us from another very difficult pairing in round three. My opponent was rated 2188, but I came very close to notching up my second scalp in a row. Let's see what happened:

I had black again. The game was another Ruy Lopez. My opponent played a fairly quiet line, and there was a lot of maneuvering in the early going. The first dramatic moment came after white's sixteenth move:

White has just moved his pawn to d4, threatening a fork by moving it again to d5. Black needs to play actively to avoid being worse. Fortunately, my development is strong enough that I can play 16. ... d5. This maintains the balance. Trades ensued: 17. Nxe5 Nxe5 18. dxe5 Nxe4 19. Nxe4 dxe4 20. Bf4 Qxd1 21. Raxd1:

The next few moves are dominated by the question of whose e-pawn is weaker. 21. ... g5 22. Bg3 Bg7:

Here there's a tactic to notice. If white takes the e-pawn with 24. Rxe4, then black has 24. ... f5! An en passant capture is out of the question, since white's rook is unprotected on e4. But if he retreats with 25. Re1, then 25. .... f4 just traps the bishop.

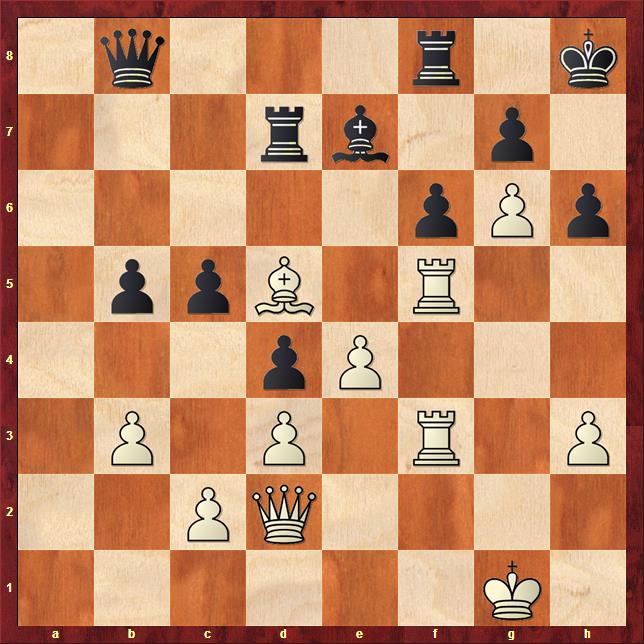

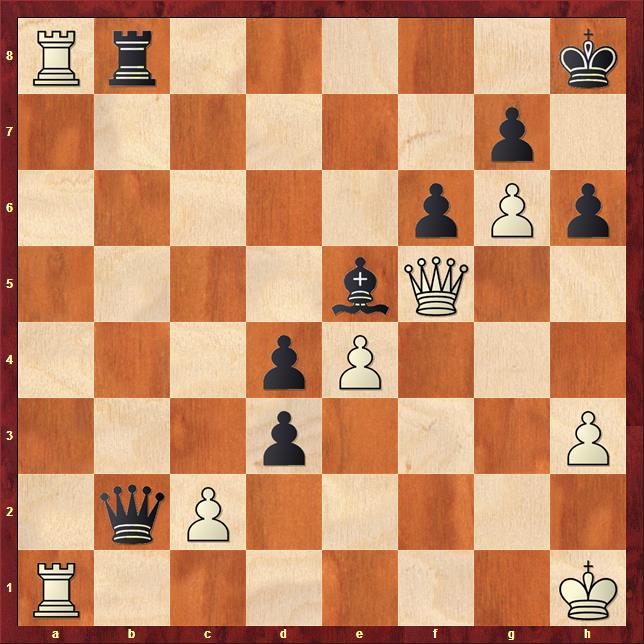

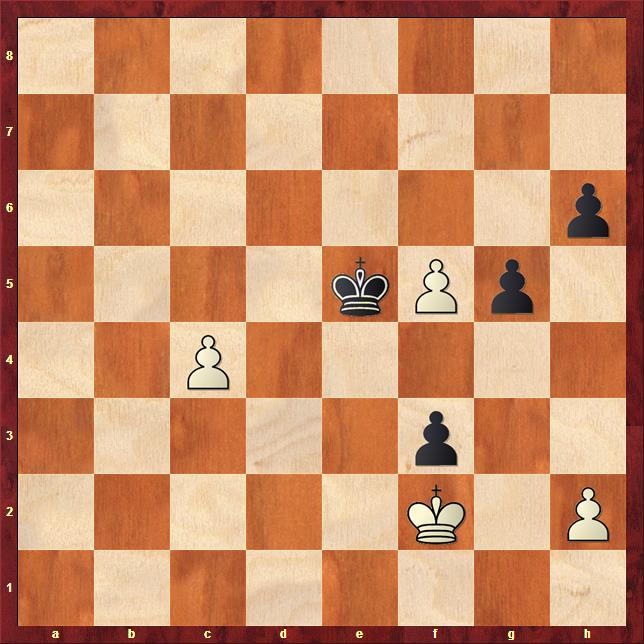

White avoided this. Skipping ahead we reached this position:

More trades have clarified the situation. This endgame should just be completely level, but white does have the more mobile pawn majority.

Up to this point I think I had played very well, but here I started to doubt myself. Confidence has always been a problem for me in chess, and here I started to talk myself into the idea that I was worse. That impression got worse after 27. ... Kg7 28. g4 Rd8 29. c4 Rd4 30. b3 bxc4:

And here I just completely forgot that white could take with the rook. In pondering the moves leading up to his position, I had only counted on taking with the pawn. So, when my opponent actually took with the rook I freaked out. Internally, I mean. Externally I maintained my best poker face.

Of course, this is all no big deal. The position is still just completely drawn and black has nothing to worry about. But after the moves 31. Rxc4 Rxc4 32. bxc4 I went into a big think. Which was a problem, since I only had ten minutes left to reach move forty. I spent about seven of those minutes deciding to play 32. ... Kf6.

I honestly thought I was losing at this point. I couldn't see what to do after 33. f3. Pushing my pawn to e3 didn't work. White would quickly surround it and capture it. But taking would lead to a pawn ending after a subsequent trade of rooks on e5. I calculated, repeatedly, that it's too slow to race my king to the queenside and take the c-pawn. I don't get back in time. But what then?

I moved by king to f6 anyway, since that was the best I could find. I resigned myself to losing a pawn after meeting white's f3 by pushing my pawn to e3, but figured my active king might give drawing chances.

My opponent thought for a few minutes and, sure enough, played 33. f3.

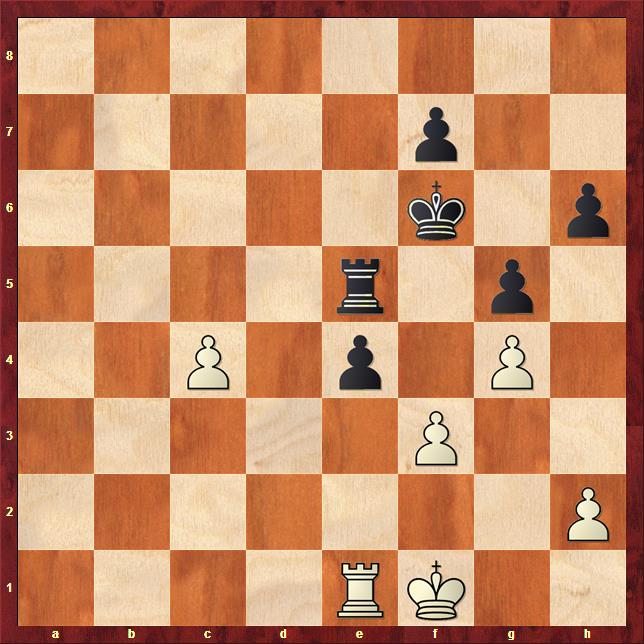

Obviously, he thought it was winning too. But then I had a brainstorm! I quickly calculated that after 33. ... exf3 34. Rxe5 Kxe5 35. Kf2:

black can still draw with 35. ... f5!. The point is that if white doesn't take then black will just push the pawn to f4 next, giving him a protected passer. But after 36. exf5

Black has 36. ... Kxf5 37. Kxf3 h5, which keeps out the white king, and gives black enough time to run over and take the c-pawn.

Perhaps, though, you have noticed what my opponent pointed out to me after the game. I was so focused on finding a way to make a draw that I completely missed the trivial 36. ... g4! which wins on the spot. If white moves his pawn to h3, black just protects it with h5. Then black's pawns are completely invulnerable, and he has plenty of time to round up white's c and f pawns. Drat!

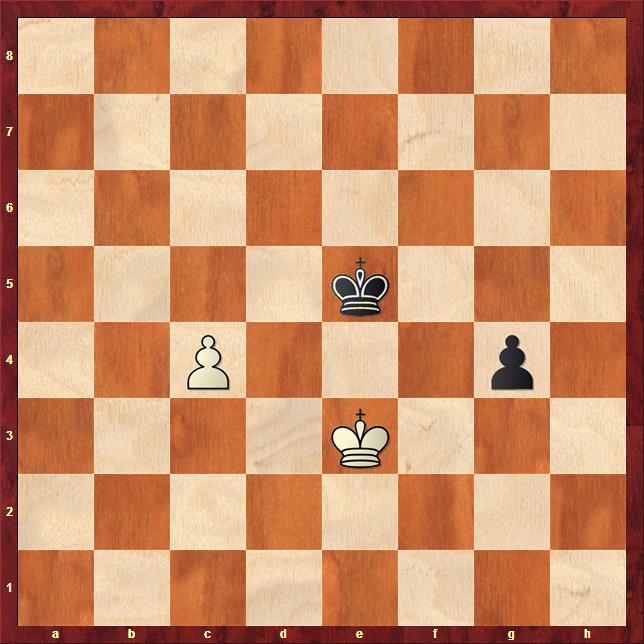

The game ended with 38. Ke3 Ke5 39. h3 g4 40. hxg4 hxg4:

and draw agreed. It's frustrating to miss such an easy win, but that's chess for you. What can you do? It was still a good game on my part, and I was happy to make a good showing for myself against such a strong opponent.

Look who stopped by for dinner on Sunday night:

The fellow in the middle is stalwart “Sunday Chess Problem” commenter Bill McNeal, flanked by Curt and Ned. We were eating at a very nice Italian restaurant that had recently opened up near the hotel. That particular restaurant used to be a kosher deli, but like I said, what can you do?

After that round, the rest of the tournament was anti-climactic. My draw was the only bright spot for the team. We got skunked on the remaining boards, which was unsurprising considering how many rating points we were giving up.

Round Four saw us paired down again, My opponent was rated just shy of 1400, but he played a very good opening. Psychologically I think it's sometimes harder to play lower-rated players than higher-rated ones. Lower-rated players are harder to predict, and you certainly feel like all the pressure is on you.

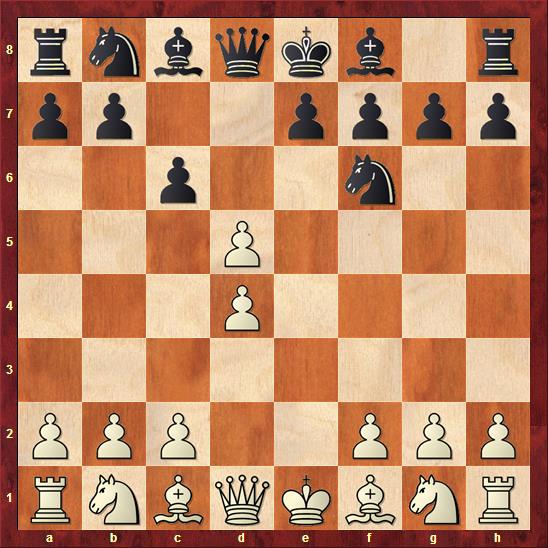

For example, here is the position after three moves. I was white:

Black had played the Scandinavian with Nf6. Black has just offered a gambit by moving his pawn to c6. Now, there are a number of crazy gambits for black in these lines. They are rare in serious games, but I had certainly lost a number of blitz games to them.

Objectively I should just be able to take the pawn. Black has a lead in development, but there's no way that should be enough compensation. And frankly, I felt confident I could outcalculate my opponent. But then I figured that taking the pawn was precisely what he wanted. A swashbuckling tactical game in which he knew the traps better than I did was not appealing. So I decided to play more solidly.

That should have gotten me in trouble. Here's the position after white's fourteenth move, which was to move my pawn to c5.

Black is just clearly better here. Had he simply retreated his queen to d8, white would be very much on the defensive owing to his overextended pawns and awkward development.

I was fortunate that my opponent decided instead to send his queen on an expedition. He played 14. ... Qb4, which is asking for trouble. He just couldn't bare to relinquish the pressure on my d4 pawn. He dug in his heels with 15. Nc2 Qa4, but now white has 16. Rd3:

Suddenly black has to be careful not to lose his queen! He is still OK, though. He sensibly played 16. ... Qa5 to give his queen an escape route. I replied 17. b4. If black had now retreated his queen to d8, like he should have done before, he would have been just fine, slightly better even.

Instead he just could not resist the pawn offer. Play continued 17. ... Nxb4 18. Ra3 Ba4, and now either 19. Bd2 or 19. Qe1 is an efficient way to win material. I played the fancier, but less good, 19. Nxb4 Qxb4 20. Rb1 Qa5 21. Bb5:

Here black can give up his queen with 21. ... Qxb5 22. Rxb5 Bxb5 23. Rxa7. White would still be winning, but black can struggle on. Instead black just acquiesced to the loss of a piece with 21. ... f5 22. Bxa4, after which he was never able to drum up anything on the kingside to justify his material deficit. The computer points out that my technique left much to be desired, but the win was never in doubt.

Curt and I finished up quickly, but Ned and Brian took their time. While they were playing, the aforementioned Matt Allman stopped by:

Here he is watching Ned ponder his next move. Actually, you can just see a bit of Brian's arm at the left side of the photo. It looks like he managed to put his young opponent to sleep.

We got it done in round four, which means we were back in the big ballroom for round five. Paired up, of course.

Now, round five is the infamous Monday morning game. Things get started at 9am, which is bad enough. But it gets worse when you realize you have to be checked out of the hotel before getting started, which means you have to be up very early indeed.

Here’s Curt taking care of business:

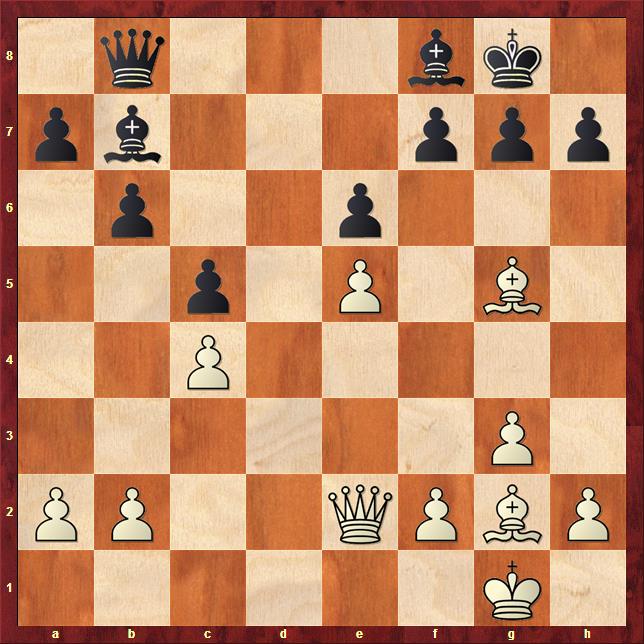

As you can see from the empty boards around him, the rest of us took care of business more expeditiously. Indeed, my game was a total snoozefest. My opponent sported a 1975 rating, which made him my only opponent in the whole event rated within 250 points of me. He had white. The opening was a Catalan. I played a solid, but passive line, and white got the expected small edge. But the position never strayed far from equality. Here’s what it looked like after twenty moves:

My opponent had just moved his queen from g4 to e2 and offered a draw. I quickly accepted.

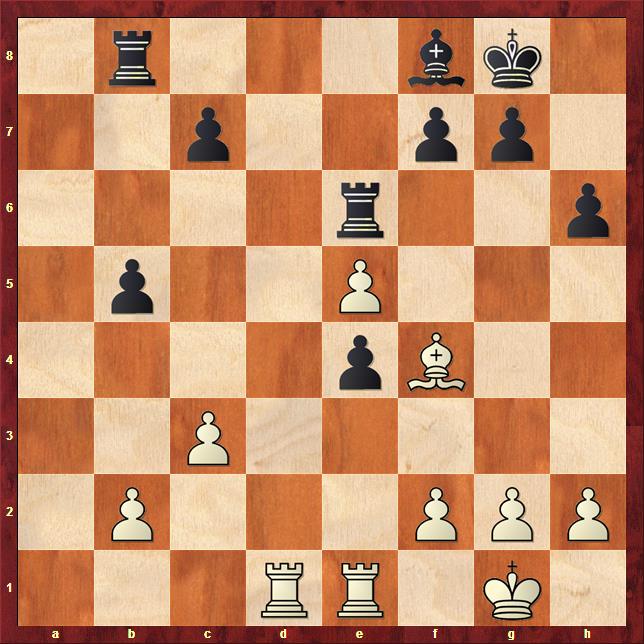

Yawn. Matt, though, opened up a big can of whoop-ass on his luckless opponent. Here’s the position after black’s fifteenth move, which was to move his knight from c6 to b4:

The opening was a, well, somewhat eccentric variation in the Advance Variation of the French Defense. Matt, playing white, had sacrificed an exchange for some reason. But here he had the chance to play one of the classic tactics in chess. The big bishop sacrifice on h7. Play continued 16. Bxh7+ Kxh7. Black could hold out a little longer with 16. … Kh8, but after 17. Qe1, white will get his queen to the kingside and that will be that. There now came 17. Ng5+ Kg8. Again, moving the king forward might have held out a little longer, but it would have changed nothing. Matt now played the delightful 18. Qb1:

After 18. … g6 Matt wrapped things up with the further sacrifice 19. Rxf7! Rxf7 20. Qxg6+:

It’s all over. After 20. … Rg7 its mate with 21. Qe8. I’ll let you work out the mates after black’s other moves.

His teammate Jon Edwards literally wrote the book on the bishop sacrifice on h7. If he ever puts out a second edition, he might just have to include this game.

And that's basically it. Technically there's a round six. It’s always a struggle to get motivated for the last round, especially when you are not in contention for a prize. Mentally you're already thinking about the inevitable return to reality the following day. In this case, though, we decided simply to withdraw from the tournament. The problem was the big snow storm that was bearing down on New Jersey.

You see, I was supposed to drive to my parents on Monday evening, spend the night there, and then drive back on Tuesday morning. But since I didn’t relish the idea of doing that in the snow, I decided just to cut my trip short and head back to Virginia that night. Ned and Brian, for their part, were feeling a little under the weather, and no one was really excited about playing the last round. So that was that!

The final tally was three wins and two draw. One win and two draws against higher rated opponents. That little performance should net me around fifty rating points. Yay me!

And I’m already looking forward to USATE 2016!

Hey, thanks Jason! Another wonderful saga of the yearly event, this time a thematic exploration of the rating-point-disparity nature of the 6-round beast.

That's a nice one by Matt, btw.

An interesting note concerning the first two photographs: both feature former Princeton Chess Club players playing with ANALOG CLOCKS (rapidly becoming extinct).

Three entertaining dramas that I can think of which involved chess: Rex Stout's Nero-Wolfe mystery "Gambit"; a "Columbo" (Peter Falk) episode, and the movie, "Searching for Bobby Fischer". Although chess was central to all three, none of them presented a real game that could be followed, and I'm not aware of that ever being done in fiction (as it has been for Bridge and Poker). No doubt because of the presumption that a general audience would not be interested in the details - but I wouldn't be surprised if the subsets of a) people who like to read, especially mystery fans and b) people who at least know the rules of chess and have played a few games, have a significant intersection. So a mystery that took the reader through an actual game or games could be worth reading to a lot of people - in case you're looking for ideas for your next book.

Thank you for the press Jason. I missed Bill over the weekend and would love to have caught up with him too.

Side note, I tried an unsound Bxh7 sac the day before and Jon schooled me up later that night. My poor opponent had no idea what he stepped into until it was too late. Of course there were many other less glorious moments. The best of this event is seeing all our old friends.

Nice job with the blog.

JimV--

I remember that episode of Columbo! It was actually the first episode of the show I ever saw, which I might explain why I have always liked it so much. Peter Falk was an avid chess player, and even once appeared on the cover of Chess Life. (I've read that Humphrey Bogart was actually an expert strength chessplayer himself).

In that episode of Columbo, there's a scene early on where the challenger to the world championship is showing him a tactical combination. You can see enough of the board to follow what is happening, and it is clearly something that happened in a real game. In the episode, the champion realized he would lose his title, and so murdered the challenger.

As for Searching For Bobby Fischer, I should mention that Jon Edwards was a chess consultant for that film.

I'll have to track down the Nero Wolfe story. I have read several of the Nero Wolfe novels, but I don't know that story.

Of course, in this context we should also mention the opening scene of From Russia With Love in which two folks are playing chess. The position is based on a brilliancy won by Boris Spassky over David Bronstein.

Bill and Matt--

Thanks for stopping by! It was great seeing both of you at the big tournament.

jrosenhouse wrote (February 21, 2015):

> […] in round two. […] So I made the waiting move 27. Kg2 and offered a draw. That’s when things got interesting. He thought for a few minutes and played 27. … Bc7.

Any thoughs about 27. … Be5 (right away) ? …

If I may be so presumptuous as to respond to Frank Wappler's suggested 27...Be5:

It still allows 28. g5 without Black having the opportunity to simply take'n'trade off pieces.

One idea that might suggest itself is to aim to place the Black g-pawn on g6, giving the King a life-raft on g7. But if 27...Be5 29. g5 g6, then simply 30. gxf6 ought to win for White.

Positions like this -- closed but with some options to consider -- require the very highest level of play. Advance king-side pawns to force the issue? You've got to be quite a bit better than decent club-level to figure these strategies correctly.

Anyhow, my 2 cents says that Black has nothing better than what Jason suggests -- wait for White to go overboard somehow. But that f8 rook has to remain defended, period.