One of the pleasures of playing in the US Amateur Team East is getting to browse the offerings from Fred Wilson's chess store. I've acquired a number of choice books from him over the years, especially in the area of chess composition. This year I was able to snatch up a copy of The Two-Move Chess Problem: Tradition and Development, by John Rice, Michael Lipton, and Barry Barnes. The book was published in 1966, but all three of these gentlemen remain prominent problemists to this day.

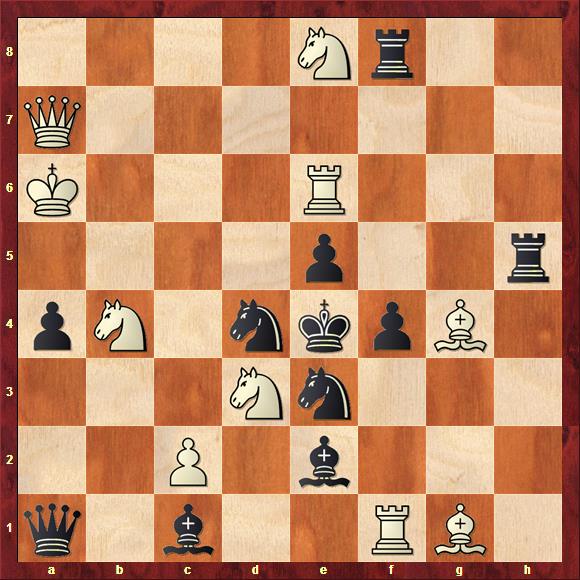

The book includes this little gem, composed by R. Bukne in 1946. It's white to play and mate in two:

We will come to the solution soon enough, but some preliminary observations are in order. Black is certainly in dire straits. Notice, for example, that if black's rook on f8 were to be obstructed then white could mate with Rxf4. Likewise, if the black rook on h5 were obstructed then white would mate with Rxe5. And if the white knight on d3 were suddenly to be unpinned, then mates by Nc5 or Nf2 are on the table. But how can we push black over the edge.

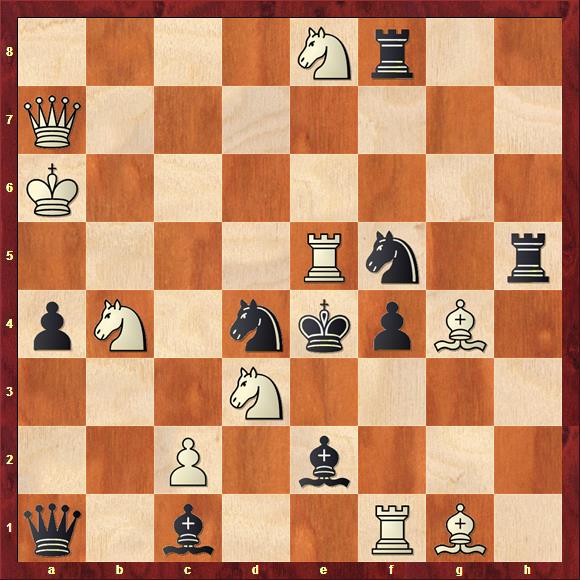

The key move is 1. e8N:

with the simple threat of 2. Nd6 mate. Black can defend by guarding the d6 square. He has four ways of doing this. The first is to play 1. ... Nef5. This defeats the threat, but at quite a cost! Since this knight obstructs both of the black rooks, we might think that white now has a choice of mates (either Rxf4 or Rxe5). But if you look more closely we find that in addition to closing two black lines, the knight has opened a guard from the black bishop to f4. That means only 2. Rxe5 mate works.

The second defense is 1. ... Ndf5. This again closes the lines of both black rooks, which again seems to leave white with a choice of mates. But a line has also been opened for the black queen to guard e5, meaning that only 2. Rxf4 mate works.

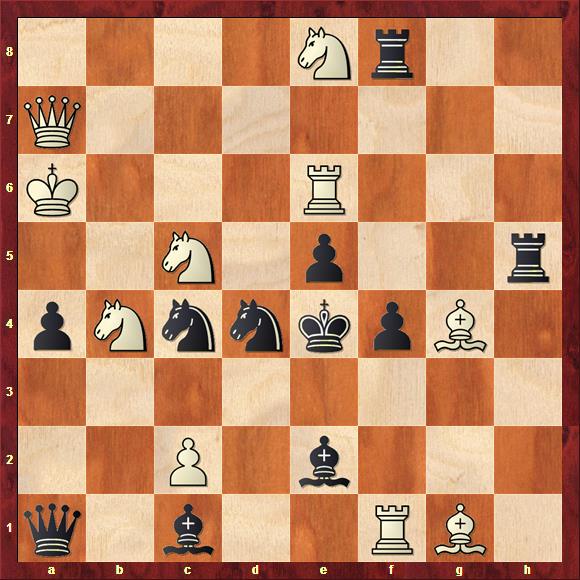

Problemists refer to this sort of thing as dual avoidance. One side appears to have a choice of continuations, but a closer look reveals that only one of them works. In this case, the apparent dual arises because of obstructions of two black pieces, a situation known as the Herpai theme.

We see more dual avoidance in black's other two defenses. Black can guard d6 with 1. ... Nc4. This unpins white's knight on d3, which seems to leave white with a choice between 2. Nc5 and 2. Nf2. But black's knight move has created a potential flight on e3. That square is currently guarded by white's bishop on g1, but Nf2 would obstruct that line of guard. So white must choose 2. Nc5 mate.

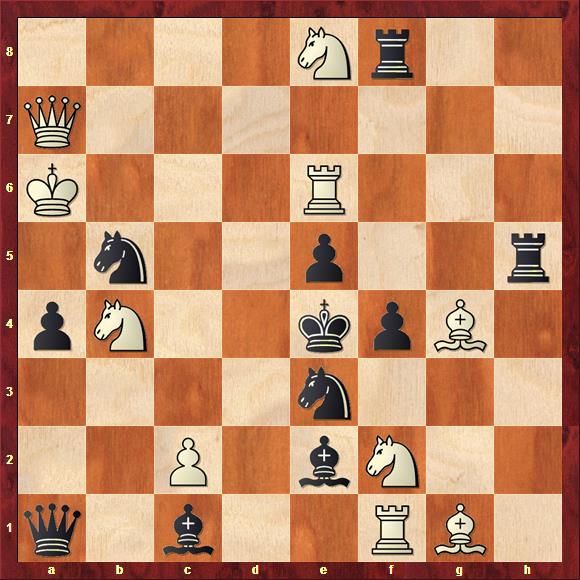

And if black tries his final defense 1. ... Nb5? This time a potential flight has been created on d4. That means white must avoid 2. Nc5, since that obstructs the white queen's guard of this square. So, this time, only 2. Nf2 mate works.

That's pretty good! Sadly, single-phase two-movers like this have largely become a thing of the past. Modern two-movers, while frequently ingenious as feats of engineering, are sometimes just too complex to be enjoyable.

Come to think of it, that's sometimes how I feel about mathematics. Too often modern, research-level math feels like it's just a tough slog, devoid of the sort of charm and elegance that got us interested in math in the first place. But that's a different post!

jrosenhouse wrote (March 7, 2016):

> […] composed by R. Bukne in 1946. It’s white to play and mate in two […]

> The key move is 1. e8N:[…]

1. e8N Bc3+ !?

jrosenhouse wrote (March 7, 2016):

> […] composed by R. Bukne in 1946. It’s white to play and mate in two […]

> The key move is 1. e8N:[…]

1. e8N Bd3+ ?

@Frank:

1. e8N Bd3+

2. cxd3 #

A gem indeed. I don't know that I've ever seen the term Herpai theme before, but it sure is pleasing.

I would certainly like to hear your thoughts on the "too complex to be enjoyable" , "devoid of the sort of charm & elegance" slog one experiences in so many fields (twelve-tone music, anyone? It's better than it sounds. Thanks to Mark Twain for this one -- he was referring to Wagner.)

Gotta be careful, though, or you end up sounding like one of the Soviet music regulators who tormented Shostakovich for his alleged "formalism".