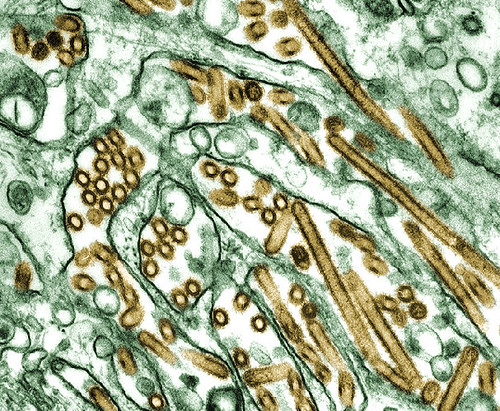

Transmission electron micrograph of

Avian Influenza Virus.

(click image for larger view in its own window)

I just received a message from ProMED-email regarding the appearance of the avian influenza virus that was just identified in Nigeria. ProMED-email is a program of the International Society for Infectious Diseases that serves to keep medical personnel and other professionals up-to-date on emerging diseases around the world. In this message, Debora MacKenzie, a writer for NewScientist.com news service, points out that;

The article [in NewScientist.com] was posted before we found out the strain in Nigeria is apparently Qinghai, that is, the same one found in wild birds at Qinghai Lake, then across Siberia, then in Turkey and around the Black Sea coast. That is exactly what one expects for wild bird spread. (The probability of that spread was also strongly supported by a PNAS [Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences] paper this week, Chen et al.) This might theoretically be down to people shipping infected meat or poultry waste to the affected areas, but I can't see why that would all be exactly the same strain of H5N1 every time, and never the Z genotype that has dominated east Asian outbreaks.

Despite the evidence that wild birds are now carrying H5N1 across long distances during migration, the data still do not show that wild birds are a significant source of the virus in local areas, nor do wild birds spread the virus to humans. Instead, domestic poultry serve as the primary source, as Debora notes;

That PNAS paper also showed it is poultry that maintain the virus in a region, spread it locally, and give it to people, not wild birds. [italics mine]

You are probably aware that for years, I have strongly asserted that there has been no evidence that wild birds been the source of avian influenza and, until recently (2005), there has been no evidence that wild birds have been spreading this virus, particularly since there were and are so many other routes of spread available; the domestic poultry industry and cock fighting birds, in particular. Knowing the details of viral spread is important because it affects public health policies, for example;

Now the virus is in poultry in Africa; that is where action must be taken: stamping out, and if possible, giving African farmers the means to isolate their poultry from wild birds, a tall order. But any action taken against wild birds in Africa now, as the FAO and bird experts have repeatedly said, is a very bad idea; it will not solve problems caused primarily by poultry and will just make matters worse by dispersing the birds.

Further, thanks to the "magic" of evolution, H5N1 will become less lethal as time goes on, unless it is maintained by humans in their flocks of domestic poultry; birds that are typically kept under closely-packed and unhygienic conditions;

Virologists say the H5N1 virus will evolve into insignificance in wild populations as long as it is not replenished by continued maintenance of the highly pathogenic strain in the poultry, where it probably evolved [italics mine].

I don't follow you. Are you saying that A/H5N1 in Nigeria is just coincidentally the same strain as that found in several other countries along this flyway? Occam's razor would say it's no coincidence at all.

I am saying that the (DNA) evidence shows it is the same strain of the virus. basically, i am quoting portions of Debora's letter and agreeing with her, as follows;

(1) the evidence shows that wild birds carried the virus from Qinghai to Nigeria (until recently, the evidence has not supported this notion)

(2) domestic poultry in Nigeria now are infected and dying from this virus after mixing with infected wild birds

(3) BUT slaughtering wild birds is the wrong way to deal with this problem because

(3a) people have only ever become ill with H5N1 after exposure to sick or dying domestic poultry

(3b) the virus maintains its lethality only in domestic poultry (due to typical poultry farming practices -- ovecrowded and unsanitary)

(3c) slaughtering wild birds serves only to disperse them, thereby spreading the virus more widely than if these birds were left alone

(3d) if wild birds are left alone, the virus itself will evolve into a less lethal form soon enough (because wild birds do not live in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions that are so typical for their domestic bretheren, and are essential for increasing virility)

I'm mostly with you here, but I'm not sure if I'm reading your wrong or if you're overstating your case a bit when you say, "there has been no evidence that wild birds been the source of avian influenza." Surely you're not discounting all of Webster et al.'s studies regarding influenza carriage in wild waterfowl?

I also agree that domestic poultry etc. can spread this amongst themselves and on to humans, but from everything I've read, the jury's still out on where it originated--whether it started in domestic poultry and moved into wild ones or vice-versa.

Finally,

I think that many folks who have done research in the evolution of virulence would disagree with such a certain statement. True, this may be the trend, but there are also cases where virulence has waxed and waned, even when other conditions held essentially the same.

my main premise is and has been that until recently, there has been little direct evidence that migratory wild birds were the primary route whereby this virus has been spread throughout southeast Asia, particularly when people have proved themselves especially adept at moving (infected) domestic birds over long distances. i do not dispute that wild ducks (especially) can and probably do carry the virus in their intestines as they move along their migratory routes, but the evidence has been ambiguous as to whether they were the MAIN source of dispersion or if domestic poultry were.

i have no idea where the virus originated, although i have read the arguments presented by both sides of this debate.

and wow, i'd be interested to read how the virulence of influenza waxes and wanes ... i can visualize the molecular underpinnings of how this might occur, but i am not sure if my imaginings are correct. is this flexibility in virulence found only in segmented viruses, or is it also seen in all viruses or even all microbes or .. ? maybe you could write something for your blog about this?

Grlscientist: Beautifully (re)-explained! Many thanks and sincere apologies for being so dense.

Whoops, meant to thank Tara!

I must be blind (can't get you straight). Thanks to both of you,

I agree--but the key words to me are "until recently". As you mention above, 2005 gave us lots of good data showing that outbreaks correlated with migration routes of wild birds, as this outbreak in Nigeria seems to. That doesn't mean wild birds are always the cause, nor does it mean that poultry movement and practices can't play a big role. Some areas one may be more critical, and another factor in a different area.

That holds for any infectious agent. I wrote here, for instance, on the changing virulence of group A strep through the 20th century. There's no reason (in theory, anyway) why highly pathogenic H5N1 couldn't be maintained in some reservoir where it doesn't cause illness. Virulence isn't an intrinsic property of a microbe--it's a product of host-microbe interactions, so what may be virulent to a chicken is just fine in, say, an eagle. Look at the Ebola Reston virus--caused monkeys to die a horrible, bloody death but only resulted in asymptomatic infections in humans. I just think they're overselling the "it will evolve to benignity" angle--that's never a sure thing.