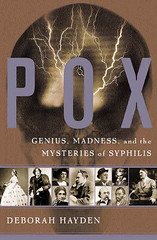

Normally I do not review books that have been out for longer than a year or so, but while I was in the hospital, I decided to celebrate Columbus Day by reading a book that was sent to me by my blog pal, Tara. This book, Pox: Genius, Madness, and the Mysteries of Syphilis by Deborah Hayden (New York: Basic Books, 2004, 2005), turned out to be an interesting biography of a bacterial infection that has baffled doctors for hundreds of years.

Normally I do not review books that have been out for longer than a year or so, but while I was in the hospital, I decided to celebrate Columbus Day by reading a book that was sent to me by my blog pal, Tara. This book, Pox: Genius, Madness, and the Mysteries of Syphilis by Deborah Hayden (New York: Basic Books, 2004, 2005), turned out to be an interesting biography of a bacterial infection that has baffled doctors for hundreds of years.

In the first part of the book, the author observes that there are two main problems associated with an case history of syphilis: first, syphilis is "the great imitator" because its multitude of symptoms are often easily mistaken for other diseases, especially since these symptoms can occur decades after the initial infection and second; patients rarely admitted that they had syphilis because of the social stigma attached to the disease. As a result, understanding the full impact of syphilis on Western culture is problematic.

But nevertheless, Hayden goes on to recount what is known about the probable introduction of syphilis into Europe, presenting evidence that suggests that Columbus himself may have been among the first syphilitics. She describes the disease's sudden and lethal introduction into Europe and how it quickly mutated into a slowly degenerative, decades-long illness. She describes the symptoms from the initial infection, the gradual physical and mental deterioration, and the inexorable progression into madness and finally, death. But according to Hayden, just prior to death, a creative euphoria occurs, whereby "the syphilitic was often rewarded, in a kind of Faustian bargain for enduring the pain and despair, by .. electrified, joyous energy when grandiosity led to new vision."

In Parts Two and Three, we learn more about who the author believes had this "new vision". Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, van Gogh and Baudelaire had it. Flaubert, Nietzche, and Guy de Maupassant did, too. In fact, Hayden claims that "Maupassant's literary leap from mediocrity in 1876 to the supreme mastery of the short story in 1880 might have been the result of a tremendous stimulation of the brain cells" by what biographer Robert Sherard refers to as "myriads of spiral-shaped germs darting to and fro."

Hayden includes some surprises in her list as well: Oscar Wilde, James Joyce and even Abraham Lincoln and his wife. The author concludes her case studies with a long-winded, meandering and not very convincing dissertation about Adolf Hilter's presumed syphilis.

However, these criticisms aside, the book is interesting and generally well-written. The first part is particularly interesting, especially for history and microbiology buffs. Readers will be divided on whether they are convinced by Hayden's arguments, but with the re-emergence of syphilis in many urban populations, this book is sure to attract attention.

Deborah Hayden, an independent scholar and marketing executive, has lectured on syphilis and creativity, most recently at UCSF Medical School, San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and the Bay Area History of Medicine Society. She lives in Mill Valley, California.

.

Nice review of what sound like an interesting book.

Typo watch: you seem to have left an italic tag open.

Thanks for this review; I'll have to look up the book and read it.

I like the concept of a "biography" of a disease or other natural phenomenon. Of course, the first, and probably still the best, biography of a disease is Hans Zinsser's "Rats, Lice, and History," a biography of typhus published in 1935, still in print, and still a most enjoyable read. Here's one great quote from it:

"Infectious disease is one of the few genuine adventures left in the world. The dragons are all dead and the lance grows rusty in the chimney corner. . . . About the only sporting proposition that remains unimpaired by the relentless domestication of a once free-living human species is the war against those ferocious little fellow creatures, which lurk in dark corners and stalk us in the bodies of rats, mice and all kinds of domestic animals; which fly and crawl with the insects, and waylay us in our food and drink and even in our love."