tags: electric fish, Brienomyrus brachyistius, mormyrids, fish, behavior, evolution

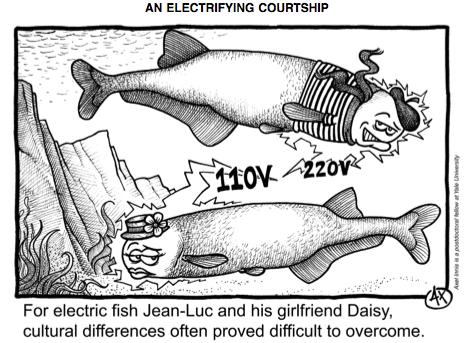

Image: JEB Biologists

As they swim through their muddy riverine homes in east Africa, the African elephantfishes use a special organ at the base of their tail to produce weak electrical pulses that enable them to sense their surroundings, detect prey, communicate with each other and, as it was recently discovered, to find a mate. Surprisingly, after listening to their electrical "buzzes", scientists discovered that these fishes engage in behavior that is remarkably similar to the courtship duets that songbirds sing.

Unlike the stunning power of electric eels, the electrical fields generated by many electric fishes are too weak to stun prey, so many early biologists, including Charles Darwin, wondered what function the faint electric fields served. But according to previous research, it is known that the waveforms produced by the fish are an electrical "fingerprint" that reveals important information about each individual's species, sex, and social status. Electrical signals are also used to navigate through the muddy waters of their home because objects cause distortions in the electrical field that are sensed by the fish's skin.

"These fish are active at night, it's pitch black, but they behave as if the lights were on," said Peter Moller, an electric-fish expert at the City University of New York. "It's like they have electric eyes."

However, the courtship "singing" of the mormyrids, as these fishes are formally classified, has remained unknown until recently, when researchers managed to entice one species in this family, Brienomyrus brachyistius, to breed in captivity.

"It is really hard to get these finicky fish to breed in the lab, and also hard to separate out the pulses from more than one fish to tell whose discharges are from whom," said Carl Hopkins of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

But since impossible things only take a little more time that usual to accomplish, Hopkins and undergraduate Ryan Wong managed to solve both problems. First, they coaxed the fishes into breeding mode by using a variety of techniques, including sprinkling the fishs' aquariums with artificial rain to simulate breeding-season conditions. Then, after the fishes were ready to breed, they used recording equipment and custom software to document both the electrical signaling and physical behavior of the fish.

The most surprising observation, Wong said, "was that there appears to be electrical 'duetting' occurring between the sexes during courtship."

Specifically, they found that courting male and female fishes engaged in alternating sequences of higher frequency "rasps" with stacatto "bursts" [hear a duet (wav)]. However, the signals aren't actually songs, because the fish sense them electrically rather than acoustically.

"Since both male and female electric fish generate signals, it is a natural for 'duetting,'" Hopkins observed.

The team also found that males and females make very specific electrical discharges before, during, and after mating. Pulse sequences varied between the sexes and between breeding and nonbreeding periods, the researchers found. For example, males produced more "rasp" and "medium burst" patterns when they were near females and during courtship, suggesting that these "advertise" the males' quality as mates. Females also produced a specific "creak" pattern only during spawning, possibly to facilitate or signal the release of eggs.

By studying the "buzzes" of electric fish, researchers hope to gain new insights into the evolution of animals' breeding behavior and communication. This study suggests that electrical signaling may have been shaped in part by sexual selection, which is the evolutionary process that has given rise to elaborate visual and auditory cues among other animal species. These signals are used by females to judge the quality of a particular male. For example, stronger male birds may sing louder and longer than their competitors or show greater stamina in courtship displays. Similarly, electrical signals may serve as honest indicators of a male's quality.

The new study appears in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Sources

So, these guys have been recording the soundtrack for mormyrid porn.

Hmmm.

Bob

They can also jam a rival's signals.

Obviously a highly charge relationship.

Bob

The cartoon would be funnier if it were "50 Hz" vs. "60 Hz."

The obvious courtship questions: "Are you old enough to volt?" and "Are you a potential mate?"

Sorry.

-- Mikey