tags: Marc van Roosmalen, primatology,monkeys, Brazil, research, biopiracy

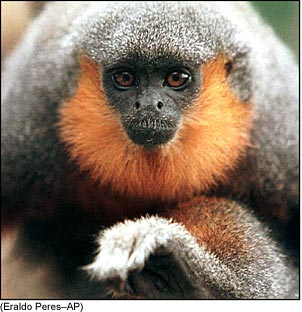

Dutch scientist Marc van Roosmalen (pictured) was sentenced to more than 15 years in prison for trying to auction off the names of several monkey species and for keeping monkeys at his house without proper authorization.

Image: Eraldo Peres (AP).

In a surprising move, the Brazilian government recently sentenced world renowned primatologist, Dr. Marc van Roosmalen, to nearly 16 years in prison. Van Roosmalen, who discovered seven species of monkeys and a new primate genus in the Amazon rainforest, was formally charged with illegally keeping wild animals at his home, with embezzlement and with improper appropriation for trying to auction off naming rights to new monkey species on the internet. However, this scientist, who was named one of Time magazine's "Heroes for the Planet" in 2000, has been made a chilling example by lawmakers. Brazil recently enacted increasingly harsh environmental laws that were intended to protect Brazil from biopiracy and other forms of exploitation.

When scientists discover a new species, they have the right to choose the scientific name. However, van Roosmalen planned to auction off this privilege to name two new monkey species on the internet and use the proceeds to protect the species in their original Brazilian habitat. Otherwise, he warned, "the rain forest will be destroyed before we even know what plants and animals are out there."

However, van Roosmalen's plans to preserve the new monkey species' habitats would prevent logging, which drew the ire of the Brazil's powerful logging interests. Additionally, many scientists point out that loggers and ranchers routinely ignore Brazil's strict environmental regulations without penalty while scientists are often prevented from conducting legitimate research.

The court instead ruled that the online auction was illegal because van Roosmalen was working at Brazil's National Institute for Amazon Research at the time of the discoveries. Thus, they claimed the naming rights belonged to the government and convicted him of embezzlement and improper appropriation.

Van Roosmalen, who, along with his wife Betty, ran a rehabilitation center for orphaned monkeys at his home, was also convicted of keeping wild animals without authorization, and selling a scaffolding that had been donated to the institute.

However, because he was born in the Netherlands, Van Roosmalen's lawyers claim he is a victim of xenophobia and fears of biopiracy even though he is a naturalized Brazilian citizen. His lawyers maintain that he was tried as a foreigner, was initially denied habeas corpus along with the right to appeal the verdict against him, was given a near-maximum sentence despite being a first-time offender and was sent to a notoriously harsh prison.

"The sentence was very stiff, it's not normal," said one of his lawyers, David Neves.

"This trial was conducted in a completely irregular fashion, and on trumped-up charges," protested Miguel Barrella, another one of his lawyers. "They couldn't prove the biopiracy accusations, so they concocted a series of spurious accusations, such as the unauthorized lodging of monkeys at his home, where he has a primate rehabilitation center."

Edmilson da Costa Barreiros, the federal prosecutor in Manaus who argued the case against van Roosmalen was quoted by A CrÃtica, the main newspaper there, as having urged that the scientist be made to "serve as an example so that others will see that you cannot do as you please at a public institution."

Van Roosmalen's conviction has had a chilling effect on scientific research in Brazil.

"Research needs to be stimulated, not criminalized," protested Enio Candotti, a physicist and president of the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science, the country's premier scientific organization, for the last four years. "Instead, we have a situation in which overzealous bureaucrats consider everyone guilty unless they can prove their innocence."

Due to previous incidents of biopiracy throughout the decades, most Brazilians support these restrictive laws. However, both foreign and Brazilian scientists protest that the laws are too harsh, too vague, provide too much power to authorities who have no scientific knowledge and have created a chilling atmosphere where every researcher is automatically presumed to be engaged in biopiracy.

"We wanted to protect the environment and traditional knowledge, but the legislation is so restrictive that it has given rise to abuses and a lack of common sense," Candotti explained. "The result is paranoia and a disaster for science. There are Talibans in the government who say they are defending the national interest, but they end up weakening and hurting it."

For example, scientists who do field research in Brazil must first have permits from as many as five different government agencies. Even though the law demands that permitting agencies respond to researchers within 90 days of their application, scientists' experiences are far different in practice: on those occasions when a permit is finally approved, the process can take as long as two years. This has greatly slowed and even prevented scientific research -- which government agencies flatly deny.

"We are trying to make the process more democratic, more open to dialogue, by inviting in all interested parties, including the military and indigenous groups, and when that happens, naturally you have people for and against" a proposal, argued Renata Furtado, at the National Defense Council, one of the permitting agencies.

International scientific organizations are also protesting this governmental action.

"Dr. van Roosmalen's situation is indicative of a trend of governmental repression of scientists in Brazil," wrote the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation in a letter signed by nearly 300 international scientists at their annual meeting in Mexico.

Foreign scientists point out that research with Brazilian colleagues is increasingly difficult due to fears of biopiracy, and that Brazilian officials are confiscating and even destroying valuable and sometimes irreplaceable materials.

"Legalized scientific research by foreigners in Brazil is doing quite well, thank you," asserted Furtado. "But we need to open this process even more so that real researchers are encouraged to come and not just backpackers."

Van Roosmalen has a reputation for being difficult to work with and has gotten into trouble with authorities several times in the past for sending research materials overseas and for transporting monkeys without a permit. Fellow researchers also noted that recognition by Time magazine caused resentment among administrators at the National Institute for Amazon Research where van Roosmalen was employed, which ultimately led to him being fired.

Basically, it appears to me that Marc van Roosmalen is a victim of politics. He is an internationally respected scientist and an outspoken and unflinching advocate for endemic wild animals and for preservation of their habitat. As a result, he was imprisoned by the government, which was probably pressured to do so by powerful logging interests, which used biopiracy as a smoke screen for their actions.

Sources

Time magazine (quotes)

MSNBC (image, quotes)

NYTimes (quotes)

MongaBay news

Marc van Roosmalen webpage

Brazil actually has laws against auctioning off the name of a new species?

This makes the Bush administration's suppression of science look very tame.

Van Roosmalen has a reputation for being difficult to work with and has gotten into trouble with authorities several times in the past for sending research materials overseas and for transporting monkeys without a permit.

Is this reputation only with Brazilian authorities, or with other scientists also? Do you know any details on this?