tags: researchblogging.org, begging calls, brood parasitism, coevolution, learning, social shaping, ornithology, Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo, Chalcites basalis, Chrysococcyx basalis

Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo, Chalcites (Chrysococcyx) basalis,

Capertee Valley, NSW, Australia, September 2003.

Image: Aviceda [larger view].

Brood parasites are birds, fish or insects that deceive unrelated animals of the same species or different species to care for their offspring. By doing so, the parasitic parent is relieved of the energetic demands of constructing a nest and raising its young to independence, so they can invest their extra energy into producing yet more young. As host parents seek to minimize their investment into raising the offspring of parasitic parents, parasitic species are forced to become better at deceiving their host species into caring for their offspring. These deceptions include both behaviors and morphologies. This leads to an escalating coevolutionary arms race between these species.

One particularly well-studied parasitic bird is the Horsfield's bronze-cuckoo, Chalcites basalis, that lives in both wooded and disturbed "edge" habitats on several islands in the Malay Archipelago of the south Pacific Ocean and throughout much of Australia, except in the most arid of regions.

This cuckoo specializes in laying a single egg in the nests of fairy-wrens, but sometimes parasitizes nests of other species such as thornbills or robins. The cuckoo chick has a shorter incubation period than the hosts' chicks, and after the cuckoo chick hatches, it pushes the host's eggs out of the nest and imitates the begging calls of the host's offspring, thereby deceiving the parent birds into feeding and caring for the interloper.

Because a female cuckoo may parasitize the nests of both the fairy-wrens and the thornbills located in her territory, her chicks must be able to competently imitate the correct begging calls -- without ever having heard them! Since fairy-wren chicks produce a short 'cheep cheep' call while thornbill chicks make a long, rasping whine, the cuckoo chick has an important choice to make almost as soon as it emerges from its eggshell. How does a newly hatched bronze-cuckoo chick learn to make the correct begging call?

"The most logical assumption was that there would be two races of cuckoo, each specializing on a different host and making a begging call that matches its host," said Naomi Langmore, a behavioral ecologist from the Australian National University. However, closer examination reveals that this is not the case: a female bronze-cuckoo successfully parasitizes both fairy-wrens and thornbills.

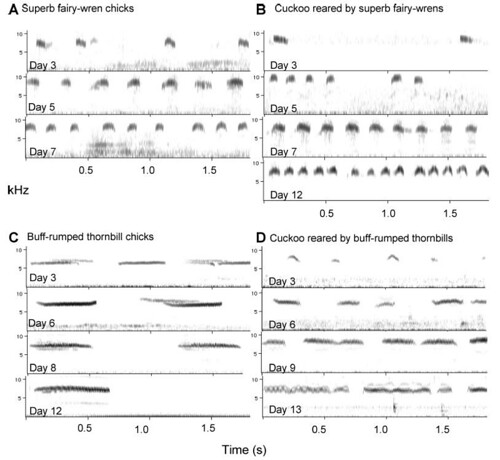

"We were amazed to find that the chicks could modify their calls," Langmore reports. She and her colleagues wanted to know how the bronze-cuckoo chicks decide which cry to make. To do this, they found nests of superb fairy-wrens, Malurus cyaneus, that had been parasitized by Horsfield's bronze-cuckoo. They removed the cuckoo egg and placed it into the nearby nest of a buff-rumped thornbill, Acanthiza reguloides, monitored the nest and recorded the begging calls of the nestlings after they hatched (figure 1);

Figure 1. Sonagrams of examples of nestling begging calls at different stages of the nestling period, for (A) superb fairy-wren chicks, (B) Horsfield's bronze-cuckoos reared by superb fairy-wrens, (C) buff-rumped thornbill chicks, (D) Horsfield's bronze-cuckoos laid in a superb fairy-wren nest, but cross-fostered to buff-rumped thornbills prior to hatching [larger view].

"Remarkably, they make the same begging call as the chicks of whichever host rears them, even though they never actually hear the host chicks," Langmore reports.

The visual appearance of the sonagrams revealed that cuckoo chicks raised by fairy-wrens [SFW-cuckoo] produced a short call with a relatively wide frequency bandwidth and a relatively high maximum frequency (figure 1B). Fostered cuckoo chicks raised by thornbills [BRT-cuckoo] also produced a short call -- at first. However, they rapidly modified their begging calls so they had a narrower frequency bandwidth with increasing duration as they grew older (figure 1D).

The team wanted to identify when cuckoo chicks began to adopt the begging calls of their host species. They found that when they were between two and three days old, all cuckoo nestlings produced a begging call with a downward deflection that closely resembled the begging calls of fairy-wren chicks. These calls remained fairly constant in SFW-cuckoos whereas BRT-cuckoo chicks modified their begging calls over time to resemble those of thornbill chicks (figure 2);

Figure 2. Canonical plots from discriminant function analysis separating the begging calls of buff-rumped thornbills, superb fairywrens, BRT-cuckoos, and SFW-cuckoos, (A) during the first half of the nestling period (N = 8 BRT-cuckoos, 12 SFW-cuckoos, 8 buff-rumped thornbill broods, and 7 superb fairy-wren broods), and (B) during the second half of the nestling period (N = 7 BRT-cuckoos, 12 SFW-cuckoos, 6 buff-rumped thornbill broods, and 9 superb fairy-wren broods). Discriminant function analysis labels each multivariate mean with a circle. The size of the circle corresponds to a 95% confidence limit for the mean. Groups that are significantly different have nonintersecting circles [larger view].

The team found that call variability declined with age in BRT-cuckoos, although variability in call duration increased with age in BRT-cuckoos -- which is consistent with the cuckoos changing their begging call to more closely resemble that of buff-rumped thornbill chicks.

Interestingly, three of the 17 SFW-cuckoos produced a begging call that resembled begging calls of buff-rumped thornbills for a short time during their nestling period. Some of these birds were full siblings to chicks being reared by thornbill parents.

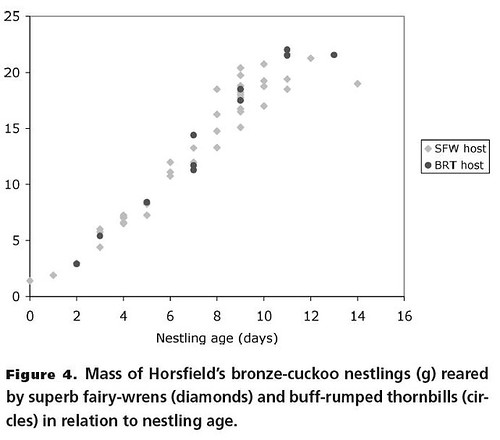

The team compared the growth and fledging rates for SFW-cuckoo chicks to BRT-cuckoo chicks and found that both did equally as well (figure 4);

These surprising findings suggest that cuckoo nestlings have a range of genetically pre-programmed begging call options and they chose which calls to produce based on reinforcement (food provisioning in this case) by their host parents. This phenomenon is known as "social shaping". If parental provisioning decreases, the chicks might switch their begging calls -- this could explain the SFW-cuckoo nestlings that abruptly changed their begging calls for short periods of time to resemble those of thornbill chicks.

"Chicks reared by a host other than a fairy-wren might find that they aren't getting fed properly because they aren't making the right call," Langmore said. "That could prompt them to apply a simple rule that says 'switch to an alternative begging call if I'm going hungry'."

Interestingly, other scientists previously observed fledgling Horsfield's bronze-cuckoos being reared by the scarlet robin, Petroica multicolor, that did not mimic the whistling begging calls of fledgling scarlet robins, but instead produced a "whine" similar to that of BRT-cuckoos. This could either result from a constraint on the cuckoo repertoire or because the host parents did not reinforce the production of mimetic begging calls.

Horsfield's bronze-cuckoo relies on host-specific mimicry to fool host species into rearing their chicks without evolving subspecies that specialize on exploiting each host species. Even though their primary host species is the superb fairy-wren, they maintain enough phenotypic plasticity that the newly hatched chicks are able to successfully mimic the calls of a secondary host species, such as the buff-rumped thornbill, by being very sensitive to the effects of social shaping.

"Cuckoos survive by fooling other birds into rearing their chicks, so they are grand masters of deception," Langmore points out.

Source

Langmore, N.E., Maurer, G., Adcock, G.J., Kilner, R.M. (2008). Socially Acquired Host-Specific Mimicry and the Evolution of Host Races in Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Chalcites basalis. Evolution, 62(7), 1689-1699. DOI: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00405.x

That little cuckoo looks sooo cute!

BUT IT WOULD BE BETTER IN 3D!!!!!!

This post added to the new blog carnival, Carnival of Evolution #1.