tags: ecology, exotic species, introduced species, non-native species, invasive species, monk parakeets, quaker parrots, Myiopsitta monachus, Michael A Russello, Michael L Avery, Timothy F Wright

Invasive species are everywhere: from plants such as Scotch (English) broom, Cytisus scoparius, whose yellow flowers bloom prolifically along roadways of North America, Australia and New Zealand to mammals such as human beings, Homo sapiens, which are the ultimate invasive species because we have invaded nearly every habitat on the planet. The widespread introduction of exotic invasive species has modified habitats, reduced species biodiversity and adversely altered ecosystem functioning across the globe -- as many as 80% of all endangered species are threatened due to pressures from non-native species. Economically, the annual cost to merely control the roughly 50,000 invasive species in the United States is estimated to be $120 billion -- greater than the annual expenses incurred by the Iraq War. So the ecological and economic costs associated with invasive species is not trivial.

But most species lack the potential to be invasive. Thus, it is very important to learn more about the phenomenon of species invasiveness so we can better identify which attributes make some species so aggressive.

To do this work, a team of researchers led by Michael Russello, a population ecologist at the University of British Columbia, studied a species of parrot that is invading numerous habitat types across four continents: the grey-breasted parrot, Myiopsitta monachus.

The grey-breasted parrot is more commonly known as the monk or Quaker parakeet. These small green parrots are popular pets and avicultural subjects, which has led to them becoming widespread around the world. Less well-appreciated is the fact that monk parakeets are an important agricultural pest in their native range throughout the lowlands of South America.

Surprisingly, despite the rapid spread of monk parakeets around the globe and their potential as agricultural pests, little is known about the geographical history of their invasions. Such information may provide important insights into the mechanisms of invasion success and potential for future range expansions.

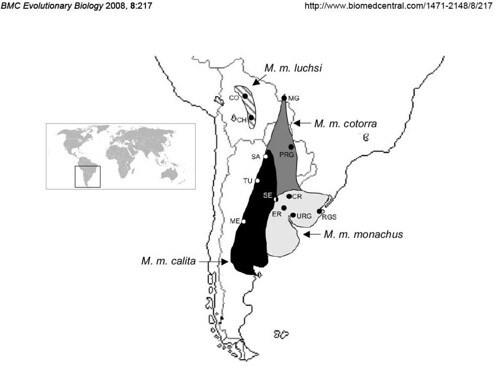

Currently, four subspecies of monk parakeets are formally recognized based on geographic variations in physical morphology, plumage coloration and nesting behavior (figure 1);

Figure 1

Distribution of Myiopsitta monachus across its native range in South America. Alternative shading denotes the individual ranges of the four subspecies including M. m. monachus (light gray), M. m. calita (black), M. m. cotorra (dark gray), and M. m. luchsi (striped). Localities of specimens sampled for this study are indicated by dots, with associated abbreviations following Table 1 (not shown). [larger view].

DOI: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-217.

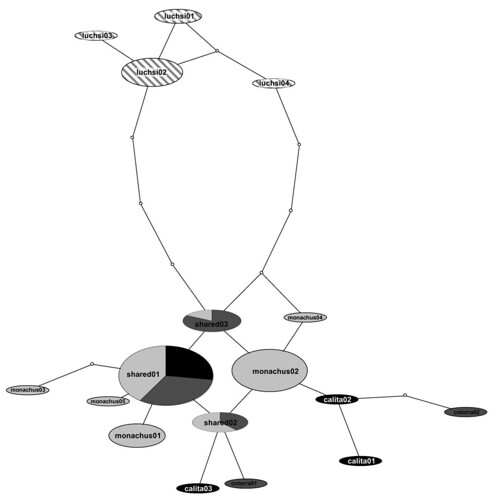

Russello and his colleagues plan to identify the taxonomic and geographic source of the invasive populations along the eastern seaboard of the United States, but they first assessed the genetic validity of the four recognized subspecies of monk parakeets, as detailed in the map above. To do this work, the researchers obtained tissue from 73 museum specimens from all four subspecies, and feather or tissue samples from 64 individuals from several locations along the eastern seaboard of the United States. They obtained sequence data obtained from a single fragment of the parrots' mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) control region (CR) and found a total of 17 distinct groups (mtDNA CR haplotypes) among these four subspecies. Using these molecular data, the researchers reconstructed a single haplotype network within which all haplotypes had a 95% probability of being parsimoniously connected (figure 2);

Figure 2

Network showing genealogical relationships among Myiopsitta monachus haplotypes sampled in the native range. Haplotypes are connected with a 95% confidence limit. The size of each oval is proportional to the frequency of the haplotype in the analysis. White dots represent mutational steps separating the observed haplotypes. Different shades represent the proportion of individuals of each subspecies exhibiting that particular haplotype (colors as in Figure 1). [larger view].

DOI: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-217.

As you can see in the above figure, the haplotypes from one subspecies, M. m. luchsi (denoted with striped ovals), do not overlap with those from the other three subspecies haplotypes (solid colored ovals). Further, as you can see from the maze of intersecting lines, the haplotypes from the other three subspecies formed a mixed assemblage, exhibiting neither geographic structure nor clustering patterns consistent with currently described subspecies boundaries.

This gene tree indicates that M. m. luchsi is a monophyletic group, forming a distinct species (according to our current definition of what is a species), within a larger paraphyletic assemblage. Further, because M. m. luchsi can be reliably distinguished from the other subspecies only by its nesting behavior, it may be thought of as a cryptic species. These results suggest that monk parakeets merit a taxonomic revision.

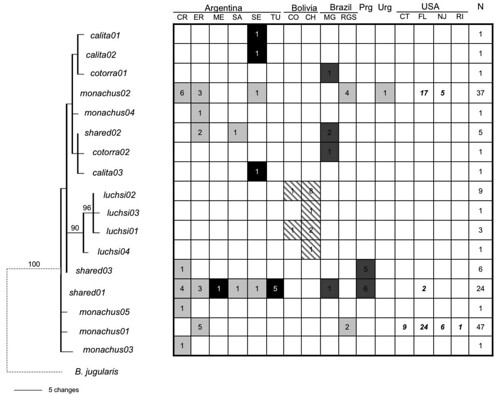

When the team went on to identify single haplotypes among exotic monk parrot populations sampled in the United States, they found that only a few were represented, nearly all of which were found only in M. m. monachus (figure 3);

Figure 3

Bayesian haplotype tree depicting relationships among sampled Myiopsitta monachus haplotypes relative to their geographic and taxonomic distributions. The names of each haplotype are as in Figure 2. Bayesian posterior probabilities (> 50%) are indicated above the branches. Each column in the associated table is a locality sorted by country with abbreviations following Table 1. Each row is a haplotype according to its placement in the tree on the left; the number of individuals at that sampling locality exhibiting that particular haplotype is indicated in each cell. Shading represents the subspecies designation for the distribution of haplotypes according to Figure 1. Bolded italicized numbers indicate the distribution of individuals collected in the naturalized range in the United States. Total number of sampled individuals exhibiting each haplotype (N) is denoted in the last column. For illustration purposes, accurate branch lengths leading to the outgroup are not shown (indicated by dashed line). [larger view].

DOI: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-217.

The the most common single haplotype found among introduced monk parakeets living along the eastern seaboard of the United States was named monachus01. In the Bayesian haplotype tree, monachus01 was the only haplotype detected among the sampled parrots from the populations in the Bridgeport, CT and Kent County, RI, and it was the most frequent haplotype in the Miami, FL and Edgewater, NJ populations. When assessed in wild populations, monachus01 was unique to populations of the M. m. monachus subspecies from Entre Rios, Argentina and Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

The second highest frequency haplotype, monachus02, was also unique to the M. m. monachus. This haplotype was found in the Miami, FL and Edgewater, NJ populations of monk parakeets and was recovered over a wide geographic area among wild monk parakeet populations: from those in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil; Soriano, Uruguay; and throughout several localities in northern and central Argentina.

Preliminary morphometric analyses as well as trapping records agree with these genetic data, indicating that the vast majority of monk parakeets captured for the pet trade were M. m. monachus exported from eastern Argentina and Uruguay. The concordance between trapping records and genetic data support the widespread view that the invasion of monk parakeets has been facilitated, at least initially, by the international pet bird trade.

But once they were introduced, the small populations of monk parakeets increased. This is due to several factors. Monk parakeets have an unusual behavior for parrots: they construct large communal nests using sticks rather than nesting as individual pairs in pre-existing cavities, and they prefer to nest on man-made structures, such as telephone and utility poles. This effectively frees them from several powerful constraints that might otherwise limit their range expansion. Additionally, monk parakeets exploit bird feeders, gardens and farmland, allowing further expansion. Studying exotic populations of this invasive species provide opportunities to follow the dynamics of their geographic range expanion and secondarily, to monitor ecological and economic costs associated with an invasive species.

Of course, one thing that should be pointed out is that most of the eastern seaboard was home to another parrot species; the Carolina parakeet, Conuropsis carolinensis, which was hunted to extinction one hundred years ago. So even though the monk parakeet is an exotic species, it is viewed by some as being a reasonable east coast ecological equivalent to this long-lost native species.

Source:

Michael A Russello, Michael L Avery, Timothy F Wright (2008). Genetic evidence links invasive monk parakeet populations in the United States to the international pet trade. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 8 (1) DOI: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-217 [open access].

At least before Ike came, I enjoyed walking around in the Texas coastal town of San Leon because I would come across large groups of monk parakeets feeding on the ground. The designated lookout would announce my presence with a loud screech, and the flock would lift off noisily and dramatically. I have seen their communal nests situated preferentially below electrical transformers, just waiting to create a power outage.

biosparite raises a question: Did the researchers have a grasp of how broadly these birds are spread in the U.S.?

My understanding is that there has been a population of Monk parakeets around Ownby Stadium on SMU's campus in Dallas for more than 20 years, and another population around White Rock Lake for almost as long. Since 1997 they have moved into southwest Dallas County, taking up residence in the football stadium in Duncanville, as well as in one Verizon Wireless tower (since expelled) and several other obvious places along major roads. I once raised a question about efforts to destroy their nests, whether any of their habitat invaded is protected, but no one from the USFWS wanted to talk about it.

It might be fun simply to ask readers here to write in and tell us whether there are any of these birds in their hometowns. I suspect they have moved much farther north than previously thought, in much greater numbers.

I just returned from Barcelona, Spain a week ago and we noticed these little parrots had seemingly invaded the city. You could not escape their shrill calls or bright green bodies flying through the air anywhere in the city.

i have seen monk parakeets in London, England; San Diego, California; and in Manhattan, NYC, enthusiastically squawking while flying over my head as I left my apartment last week, in fact. i cannot tell you how long they've lived in any of these locations, though.

There are two long-lived colonies of Quakers in New York City - one in Brooklyn and the other in the Bronx. Check out http://www.brooklynparrots.com/. I used to be 'owned' by a very obstinate quaker. I loved him dearly, as noone else could... After he died, I was cheered up by the wild quakers that lived near me in the Bronx.

You can see the distribution of the Monk Parakeet across the Americas at

http://ebird.org/ebird/GuideMe?cmd=quickPick&speciesCode=&bMonth=01&bYe…

This map just represents the Monk Parakeet sightings which have been reported to eBird.

12 states have banned the Monk Parakeet.

The Monk Parakeet has been counted on Christmas Bird Counts in 23 states and the District of Columbia.

13 states have placed the Monk Parakeet on their official state bird checklists. Unfortunately, my home state, Louisiana, has not.

Could it be that there is some variant heat absorbed from the nesting sites into those huge nests? It would help provide the necessary warmth for survival at night.

I live by the Monk parakeets in New Jersey. They have been in the town of Edgewater for 30 years. I personally think that if they were so invasive they would have left that town many years ago and spread out all over northern NJ.

Man has already wiped out the only North Eastern American Parrot as was stated by you, and man is now trying to reintroduce the Thick Bill Parrot in Arizona that again man had hand in their demise.

When Central Park was built in NYC New York man brought all the birds, that were familiar to them from their home countries, so more than likely many of your favorite birds you see that exploit your back yard bird feeders really shouldn't be on this continent either.

Just to sum up. The Monk Parakeets stay in one area and set roots so to speak. They don't travel in search of farmers fields to plunder, there like any other bird species that will take a free hand out at the local bird feeder. They don't push any other species out of their area they live in harmony with them.

I have read that the farmers in Argentina would be compensated monetarily for damage that they said the Monk Parakeets would do to their crops. So I cant say this is true or false but when was the last time you heard that the price of Apples Peaches or Pears went up because a flock of Monk Parakeets exploited a farmers field or orchard in Florida.

I think it was just the powers that be in government that over reacted to hearing this in the 70's and put them on the dangerous species list in our State of NJ. Which by the way no one can handle, help or own and I would also think experiment on. How many birds did you collect and did they die or were they released just so we could know what species and subspecies there from.

I mean the Knowledge is good but maybe we should put our time into redesigning transformers and structures that they build around than trying to eliminate a beautiful species that helps to make up the diversity our country.

I don't know, I just think there listed incorrectly. There not dangerous or invasive compared to the release of the bird species from Europe in Central Park NYC which are now all over most of this country.Monk Parakeets have spent 30 years in one little town in Northern New Jersey, It doesn't say invasive to me. How about you?

i live in brooklyn, ny and around 10 years ago my family and i started noticing that we had these little green parakeets living in the trees outside of my house. the population grew and grew - and now they have a huge population with nests that sit atop telephone poles for miles.

we always thought it was a bit strange, and there are many opinions about how they got here - most of the people in my neighborhood say that a truck that was taking them to a pet store was overturned and the parakeets got out and made our neighborhood their new home. some say that in the 1960's these parakeets were supposed to be sent to a pet shop but were accidentally released at kennedy airport. some even say - and this is bizarre - that the parakeets were blown over during hurricane gloria in the 80s. whatever the origin story is, they are here, and they don't migrate. its actually pretty wonderful. everybody loves the parakeets and we dont find them to be invasive at all.

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B07EEDC153BF93AA25755C0…

http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/education/miele/MonkParakeets.htm

there is a small breeding population of mostly red-masked parakeets (a.k.a. "cherry-headed conures"), Aratinga erythrogenys, nesting around the Telegraph Hill area of san francisco and ranging through the northeast waterfront area of the city. they were featured in a documentary called "The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill" just a few years back....

Interestingly although they have been in Australia since at least the 1930's, and are one of the more common exotic parrots kept as pets in Australia, they have never established a wild population. Nor has any other exotic parrot species.

Perhaps it is due to the lack of any wild caught imports, and the failure of captive bred parrots to learn the survival skills needed in the wild, or perhaps the competition from the abundant native parrots has proved too much.

Avinet, Queensland

that's fascinating, mike. i would guess that competition from the native parrots has kept monk parakeets from becoming established in australia, but if that's the case, then that implies that, when monk parakeets do become established, they are either (1) filling an empty ecological niche or (2) are successfully out-competing native species here in north america and on other continents where they are establishing themselves.

London's very common Parakeet is the Rose-Ringed,Psittacula kramer, originally from the foothills of the Himalayas and so,eminently suited to our climate.

There are various theories about their origin including release by Jimi Hendrix or escape from the film-set of 'The African Queen' but most likely they are the result of numerous releases and escapes from unknown cage-bird enthusiasts.At any rate there are now 10s of thousands particularly in West London and around North Kent.My son saw them in Istanbul, a blogger in Bahrain photographed them in his garden and I believe I've read of them in Amsterdam, so a very successful exotic species.

Unlike Monk Parakeets they utilise holes in trees for nests and there have been concerns expressed for competing species such as woodpeckers.Vineyard owners have complained about crop destruction but of course we're not exactly over-endowed with vineyards even these globally-warmed days.

The only UK colony of Monk Parakeets I'vs heard of was about 50 strong and located around Borehamwood,to the North of London.Allegedly there was an individual who fed and to an extant looked after them so they were arguably not truly wild and cetainly far from established in the way you describe in America.

Great article. I've been following the Northeast flocks of monks for about 3 1/2 years now and give monthly tours (AKA "Wild Parrot Safaris" for curious New Yorkers who've never seen wild parrots in their city.

The fact that it seems there seems to be only one main type of monk parakeet (monachus01) in the NE area suggests that there was only one main supplier of monks during the time when importation was widespread. I am intrigued by the appearance of monachus02 in Edgewater, NJ. On several occasions, I have photographed feral leg-banded birds amidst the wild flocks there. Monks are illegal for sale in NJ, which suggests that such leg-banded birds may have flown over from New York State (where they are legal to sell, but only if banded). Perhaps there was a second source for these additions to the flock: domestically bred birds whose DNA makeup differs from the original group of birds released long ago.

This is the USDA's side of the story.

The authors of this article work for the USDA, the Federal Agency that murders and experiments on the wild parrots.

That's right, folks--your tax dollars at work, killing innocent little birds.

The info here is phony propaganda, just like the lessons they teach to the employees of the utility companies that pay them the big bucks for their trainings (I have copies--e-mail me if you want to see them).

If the USDA were to admit that the parrots are not invasive, they wouldn't make any money on trainings and killings.

See what they did in Connecticut: http://www.ctquakers.com/murder.htm

These birds are not becoming ubiquitous; all this study shows is where the birds came from.

If you want to read a real study with real data, read the studies done by Dr. Michael Gochfeld in the parrots' native territory and here in the U.S.

When did the USDA ever grab any of Edgewater's birds for research?

Don't believe evrything you read--not unless you are given tangible proof.

The USDA just wants to be certain they can keep on killing. Don't let them! It's unnecssary, inhumane, and cruel.

There are humane alternatives--just ask NJ's utility company, PSE&G.

Alison

www.EdgewaterParrots.com

I love them. They are illegal in my state.

I find it disturbing how many people care so little about the environment as a whole that they are willing to defend the presence of invasives just because they personally like a species. U.S. parrot lovers, ask yourselves what evidence you would need before you would agree that monk parakeets are invasive and need to be eradicated. A commenter above noted they've been spotted during the Christmas bird count in 23 states, and population estimates range from 20,000 nationwide to 150,000 in Florida alone. Either way, you don't think that might have an impact on native wildlife? Please don't be like the mute swan defenders, who continue to deny the species is invasive despite massive yearly population growth and well-designed studies that have quantitatively shown how destructive the swans are to U.S. wetlands. Is your desire to have wild parrots around worth even a chance that they might contribute to the decline or demise of a native organism? I would hope that you can really love watching feral colonies of monk parakeets, yet still support their humane removal for the sake of our native species.

To Chelydra:

Please note that monk (quaker) parakeets are not agriculatural pests in the United States.

They have become established in cities where they nest primarily on utility poles and similar structures and survive by eating from bird feeders and introduced ornamentals. In these urban areas, they have adapted to niches necessarily abandoned by "native" species -- one of which was the Carolina parakeet whose extinction was partly produced by the introduction of the honey bee which took over their nest cavaties.

What is and is not a native species changes. Have you heard anything about killing off bees? Quite the contrary, we are trying to conserve European honeybees even though they were introduced.

See the book PARROTS IN THE CITY for an objective overiview of the existence of Quaker parrots outside Argentina.

Within a very short time, the USDA will begin delivering birth control to squirrels and Quaker parrots. However, if you'd like to see the potential of an appropriately appreciated quaker parrot, take a look at this: http://cosmos.bcst.yahoo.com/up/player/popup/?cl=10625886

Is it really in the best interest of the planet to eliminate one of the only speices that can communicate with humans in our own words? Shouldn't we be more instead in trying to find out what they know as the most highly adapted (by learning nest building rather than being limited by cavaties) parrot?

Yes, but honey bees have predators, like tanagers. Monk Parakeets, like native crows and non-native starlings, House Sparrows, and pigeons filled the urban niche because, for one reason, lack of predators. Ecological constraints on distribution, because of filling a vacant niche, like predators, must be in place before invasion to avoid the spread of numbers. It is true that in South America, the birds are a threat to farmers and grain crops. Eurasian Collared Doves, Cattle Egrets, and Mute Swans have all, plus others, been considered invasive by the Feds., and Double-crested Cormorants have been managed aggressively on river islands to promote heron species' breeding; the cormorants take over heronies. See the Federal Register for a list of what the Feds. consider "invasive". I agree that these are pretty birds, but so are captives to wild of LA and the Miami area. In Scottsdale, AZ, Peach-faced Lovebirds are established. This is quaint and romantic, but I agree that invasive birds out compete native birds, no matter how ugly.

In response to comment #11 by Mike Owen. According to one expert birder in Louisiana who studied Monk Parakeets, captive bred birds cannot survive in the wild. This is supported by Christmas Bird Count data which has many examples of one to a few Monk Parakeets being recorded in a past year but not succeeding years. One exception to this is that they might survive if there was an already existing colony of wild (feral) Monk Parakeets which they could join.

To Chelydra:

You may get your wish. The United States Christmas Bird Count for the Monk Parakeet peaked in 2003-04 at 4,452 and has decreased every year since then, reaching 2,848 last Christmas.

Bird feeders are the greatest way to bring all kinds of exotic species of birds into ones life....

I currently reside in South Jersey....

I have a glass bird feeder in my front yard and it really is amazing all the beautiful birds that come into my yard...

Plus it makes me feel good that I'm providing them with a good food source.....

Thanks,

Chris