Recently, I described how the most frequent killer of children in the developing world wasn't 'the Big Three' (AIDS, malaria, and TB), but boring old pneumonia. Well, the second greatest killer is diarhhea. And several factors are leading to increased treatment failure of diarhhea.

Actually, it's not that treatment is impossible because the diarhheal strains are resistant to many antibiotics. Treatment failure is occurring because the antibiotics that still work are not available in these countries. The problem is resistance plus poverty. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

First, some of you might wondering why one would use antibiotics to treat diarrhea. Unless the situation is dire, typically, the recommended therapy is intravenous rehydration and rest for several days to week (depending on how long the illness lasts). In many cases, antibiotics are simply not needed (occasionally, in children, chloramphenicol or other antibiotics are used to treat severe typhoid fever, Salmonella typhi and paratyphi). Unfortunately, in the developing world, patients, or the parents of child patients, don't get sick days. There is a severe economic need to treat and end the symptoms as soon as possible. For a family near the margin, even four or five days in the hospital is an unaffordable burden between the lost work days and the cost of hospitalization (What about health insurance, you ask? You're not serious, right?). Consequently, these infections are treated with antibiotics.

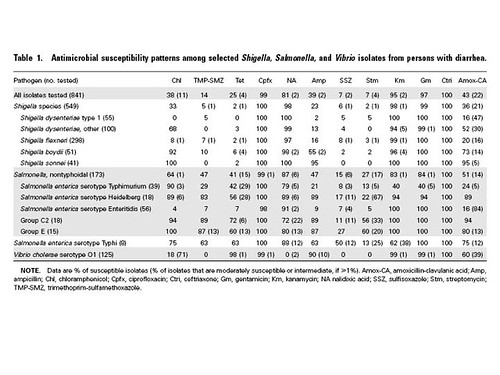

A recent survey in Kenya of antibiotic resistance in the diahhrea-causing bacteria of Salmonella, Shigella, and Vibrio indicates that many antibiotics are rarely effective against these organisms:

(larger version here)

Cotrimoxazole resistance (also known as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) is particularly disturbing, since it is used as the first line of antibiotic therapy throughout the developing world. Cotrimoxazole resistance is so common, in part, because it is used so widely--and misused so widely. A second factor could be the use of cotrimoxazole in HIV patients to prevent bacterial infections: essentially, we are bathing much of Africa in a dilute solution of cotrimoxazole. The potential good news is that many antibiotics are still effective. Tragically, they are literally not available, largely because of cost:

The antimicrobial prescribed most frequently for diarrhea was metronidazole (in 14% of cases). For the antimicrobials active against GNRs that were prescribed most frequently, susceptibilities of Shigella, nontyphoidal Salmonella, and Vibrio species were low (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 14%; ampicillin, 41%; amoxicillin-clavulanate [prescribed for only 5 illnesses], 65%; and tetracycline, 29%; see above table). Susceptibilities to kanamycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and ceftriaxone were >95%; all were used infrequently or were unavailable in the community.

Keep in mind, that the cost of kanamycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, and ceftriaxone in a developed nation would be trivial, but in poor countries, even these drugs can be priced out of reach when there are limited resources. This is one more reason why antibiotic resistance is such a serious problem--and just like all of the sexy diseases, it's global too.