![]() Living in a world of sunshine and electricity, we tend to take light for granted. Heck, we complain when clouds diminish our bright sunny rays. But dip just beneath the surface of the ocean and light becomes a rare commodity. More than half of the light that penetrates the ocean surface is absorbed in the first three feet. As you go deeper, different colors disappear. Red is the first to go, followed by yellow and green, until you're truly immersed in murky blue. At about 200 m deep, there is so little light that plants cannot survive, as there isn't enough light energy to power photosynthesis. Drop down again to 850 m and you no longer see any light because our eyes aren't sensitive enough to detect the trace that trickles down. Dive another 150 m down to 1000 m deep and you enter the aphotic zone, where even the most sensitive eyes no longer see the sun.

Living in a world of sunshine and electricity, we tend to take light for granted. Heck, we complain when clouds diminish our bright sunny rays. But dip just beneath the surface of the ocean and light becomes a rare commodity. More than half of the light that penetrates the ocean surface is absorbed in the first three feet. As you go deeper, different colors disappear. Red is the first to go, followed by yellow and green, until you're truly immersed in murky blue. At about 200 m deep, there is so little light that plants cannot survive, as there isn't enough light energy to power photosynthesis. Drop down again to 850 m and you no longer see any light because our eyes aren't sensitive enough to detect the trace that trickles down. Dive another 150 m down to 1000 m deep and you enter the aphotic zone, where even the most sensitive eyes no longer see the sun.

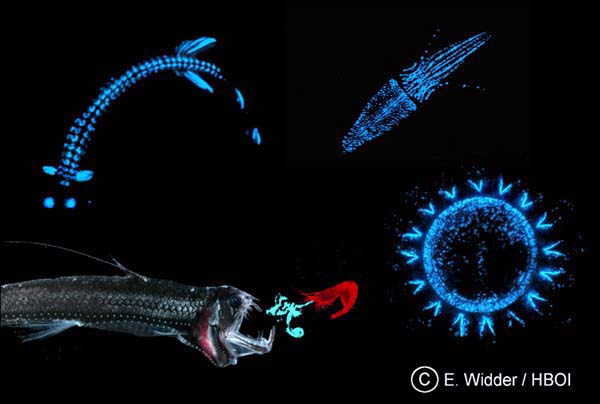

It is in these dark depths that many creatures have adapted to produce their own light. Called bioluminescence, this biologically created light plays a big role in the lives of deep-sea creatures, being involved in everything from camouflage and signaling to hunting. While only a handful of organisms above the murky depths have bioluminescent capabilities, it's estimated that 90% of deep-sea marine life produce light in one form or another. This plethora of glowing organisms have given deep sea biologists plenty to study.

It is in these dark depths that many creatures have adapted to produce their own light. Called bioluminescence, this biologically created light plays a big role in the lives of deep-sea creatures, being involved in everything from camouflage and signaling to hunting. While only a handful of organisms above the murky depths have bioluminescent capabilities, it's estimated that 90% of deep-sea marine life produce light in one form or another. This plethora of glowing organisms have given deep sea biologists plenty to study.

All the fish so far studied use nerves to somehow turn on and off their chemical lights. Nerves provide an excellent means of control as they can be fired quickly and selectively, allowing for rapid and precise responses. But new research into one particular species of deep sea fish, called the velvet-belly lantern shark, has found that it uses hormones instead to turn on and off it's bright display. This alternate route suggests that bioluminescence has evolved multiple times, a process called convergent evolution.

The velvet belly lantern shark (or simply velvet belly), Etmopterus spinax, is a fairly small member of the dogfish family and is one of the most common sharks in the deep northeastern Atlantic. It tends to hang out somewhere around 500 m deep, where there is still a trace of visible light from above. If it's name didn't give it away, the velvet belly lantern shark is capable of bioluminescence, and lights up its belly to camouflage its shape when viewed from below, a process called countershading. While it's not fished for profit, large numbers are caught as bycatch in other deepwater commercial fisheries, and the intense fishing pressure throughout it faces its range does worry conservationists who recognize that like other sharks, its slow reproductive rate make it highly susceptible to overfishing.

The researchers first thought to investigate hormones in this species because the shark's bioluminescent cells, called photophores, weren't hooked up to a complex nerve system like in many other bioluminescent fish species. They decided to test if nerves controlled the shark's light-producing cells by injecting neurotransmitters, such as adrenaline and GABA, into the skin and measuring the light produced with a luminometer. None of the neurotransmitters tests were able to stimulate the skin to glow. If the photophores not linked to nerves, the scientists thought, they must be being triggered by some other mechanism. So they began investigating the possibility of hormonal controls.

Indeed, they found that three hormones control this species bioluminescence on and off switches: melatonin, prolactin and alpha-MSH. Melatonin is well known in humans for controlling sleep regulation. But when skin patches of lantern sharks were exposed to the hormone, they lit up for several hours. Similarly, exposure to prolactin also led to light production, though the glow was brighter lasted only about an hour. Alpha-MSH, the researchers found, did the exact opposite - when skin was exposed to it before the other two chemicals, the lights stayed off.

Evolutionarily, it makes sense that this little shark would control its skin lumination with hormones. While in bony fish, skin color is controlled by nerves, the cartilaginous fish (including sharks, skates and rays) control their skin pigmentation with hormones. It is thought that nerve control of skin pigmentation is a later evolutionary development, occurring after the split between cartilaginous and bony fish. While hormonal regulation doesn't allow for as rapid or precise a response as nerve triggering does, it does work well, and using a hormone that already is triggered by darkness like melatonin makes perfect sense.

Evolutionarily, it makes sense that this little shark would control its skin lumination with hormones. While in bony fish, skin color is controlled by nerves, the cartilaginous fish (including sharks, skates and rays) control their skin pigmentation with hormones. It is thought that nerve control of skin pigmentation is a later evolutionary development, occurring after the split between cartilaginous and bony fish. While hormonal regulation doesn't allow for as rapid or precise a response as nerve triggering does, it does work well, and using a hormone that already is triggered by darkness like melatonin makes perfect sense.

This drastically different mechanism of turning on and off bioluminescence suggests that sharks and other fish evolved the ability to produce light separately. It's likely that the same evolutionary pressure to produce light - the dark depths of the sea - led both groups of organisms to evolve mechanisms of glowing. The researchers believe that further investigation into other light-producing sharks will find that they, too, use hormones to control their bioluminescence.

Studies like this one show that we still have much to learn about these glowing creatures that live so far below the ocean's surface. The more we explore these depths, the more we learn about the fascinating organisms that survive these cold, deep waters and how they live in a world without light.

Claes, J., & Mallefet, J. (2009). Hormonal control of luminescence from lantern shark (Etmopterus spinax) photophores Journal of Experimental Biology, 212 (22), 3684-3692 DOI: 10.1242/jeb.034363