Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun, never really has had a great picture taken of it. There are a number of reasons for this, such as:

- It never gets more than 28 degrees away from the Sun, meaning we get two hours after sunset -- max -- to look at it.

- Because the sky is still light, it's very hard to get a good resolution image from the ground.

- Because of its proximity to the Sun, operators refuse to point space telescopes (like Hubble) towards Mercury, for fear of frying the telescope.

- Mercury is far away and tiny, making for a disastrous photographic combination.

From Earth, this is the best picture we've ever taken of Mercury, courtesy of Boston University:

No joke. That's not impressive at all, is it? Nevertheless, we sent a spacecraft, Mariner 10, to it in 1974/5. Mariner 10 took some great images, which we then processed, cleaned up, and stitched together into a giant mosaic, giving us a glimpse of our Sun's closest companion:

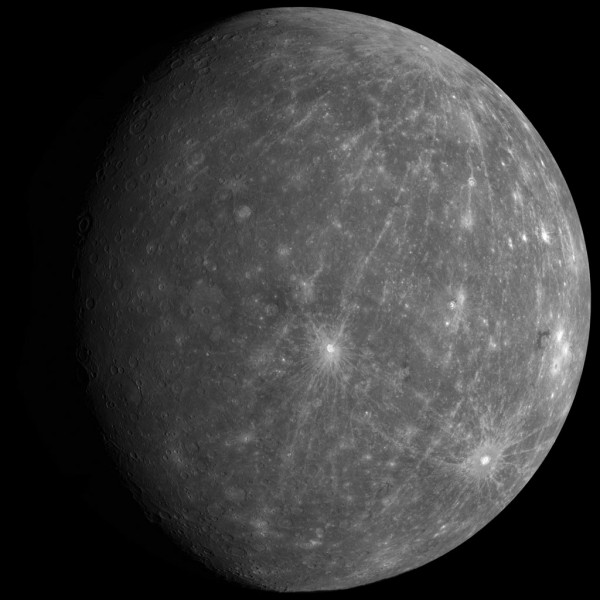

With Messenger up and running, it was only a matter of time before we got a new, superior look. Thanks to Jason Perry, we now have a new image of Mercury, illuminating nearly a full disc of the planet and made from 66 separate high-resolution images. You can click the picture below to enlarge it.

But Jason went a step further and offers the full 20 Megabyte .png file for download! So enjoy the new view of our sunny neighbor, and thanks to Universe Today for the story!

Nice. Thanks.

All of these photos that MESSENGER is sending back; are they approximate true color, or monochromatic?

Another fascinating post Dr. Siegel! I wonder, when I look at the moon (our moon) I notice more craters towards the south pole than elsewhere. I am seeing similar craters at the pole in these photos. Is this a visual anomaly of some sort, or do they actually get whacked more at the poles?.... It just seems like the craters would be fairly evenly dispersed over the surface, and I'd think a few billion years would be time enough to eliminate chance.

Reason 3.5. Operators of ground-based telescopes refuse to point at it for fear of letting sun-light into the dome, warming it up and stuffing up the night's observations.

Interesting point about the poles. I, too, would have thought that there would be fewer there, since, like the Earth and the Moon, Mercury's axis is roughly perpendicular to the orbital plane and the bulk of the solar system's matter is along that very plane.

That may be the best ground-based photo, but it seems to be far from the best ground-based radar observations. Apparently, the scientists at Goldstone and Arecibo are not afraid to aim towards the sun. :D

If you look at that 20 Megabyte image and scroll around it, there are craters everywhere. It's only in the low resolution image that the cratering seems to be very unevenly distributed. Most cratering took place during the late heavy bombardment. The "smooth" areas have been modified after the bombardment, but you can still see the evidence of the craters because they haven't been completely filled in.

This is a totally uneducated guess, but I think it's visual. The poles are always close to the terminator, and craters along the terminator stand out more, because they're being illuminated at a near-horizontal angle.

I wonder, when I look at the moon (our moon) I notice more craters towards the south pole than elsewhere.