We shall not cease from exploration and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started... and know the place for the first time. -T.S. Eliot

Yesterday, President Obama delivered his first State of the Union Address, and talked about a number of things that ranged from inspiring to disappointing. But one thing that didn't make it into the address was the rumor that NASA's Constellation program (including the Ares Rocket designed to launch crews) will lose their government funding.

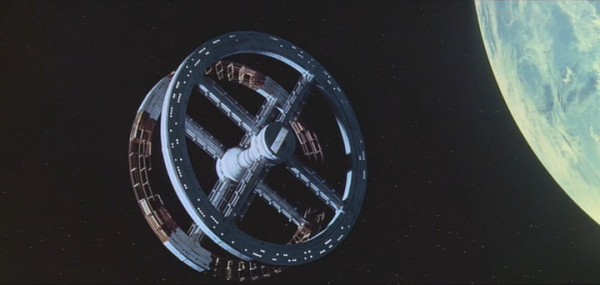

(Please note: what follows is my opinion, and I take responsibility for it.) If this actually happens, I think this is one of the best things that could happen to NASA. When the Apollo program was at its height in the late 1960s, we had a grand vision of where we were headed. Walking on the Moon was going to just be the first step; our goals for the future were going to include permanent outposts in low-Earth Orbit, on the Moon, and eventually the exploration and colonization of other worlds. It was no stretch of the imagination to believe that, 30 years in the future, we would routinely have people who lived in space aboard stations with their own artificial gravity, like in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

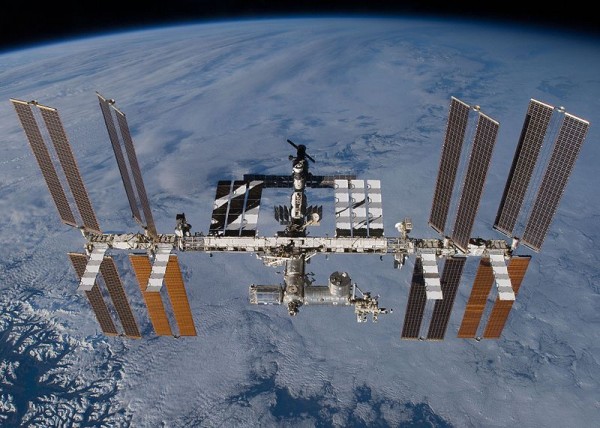

And doesn't that seem like a pipe dream today? After the end of the Apollo program in 1975, the only manned space mission run by NASA has been the Space Shuttle program, which cannot reach beyond low-Earth orbit. Although it has been marginally scientifically useful, there simply isn't the awe that was present in traveling to the Moon. Moreover, the largest, most successful "space station" that we have is the ISS, which looks anything but impressive when compared to 1968's science fiction.

Moreover, the ISS is fairly useless scientifically. So in 2004, when then-President Bush announced a new space initiative for manned spaceflight, I was at first optimistic, and then almost immediately devastated. Why was this so disappointing to me? Let's go over some reasons.

- There are no awe-inspiring short term goals.

- The vision's major mandate -- establishing an extended human presence on the Moon -- has no clear scientific merits.

- It is already way over-budget and behind schedule, delivering lackluster results to this point.

- The vehicles presently in development are insufficient to take us beyond the Moon anyway.

- The long-term goal -- to send a team to Mars -- is unreachable by even the most optimistic estimates until the 2030s.

- It affirms the perception that the space program is a waste of tax dollars.

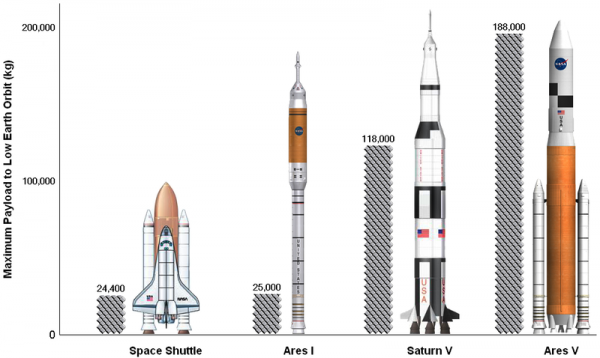

It is appalling to me that this vision is still in place as current policy. The Ares rockets currently in development (Ares I and Ares V) are barely improvements in any way over the Saturn V rockets from nearly half a century ago, even on paper!

What was even worse? When this vision was instituted, it basically cost NASA $1-$2 billion per year to fund it. But NASA's funding was not increased to cover that cost, causing them to scrap about 5-10% of their total budget to make room for this new initiative.

While there are many opinions out there on this, I am unequivocally in support of Obama's pulling the plug on this monstrosity of a funding-eater. NASA has already spent about 8 billion dollars on the Ares rockets and other Constellation-related programs, and -- in order to get humans back to the Moon by 2020 -- will need to spend around 100 billion total. Keep in mind that NASA's entire budget for this fiscal year is just over 18 billion dollars, so if NASA is no longer bound to do this, they will be free to fund missions that are actually scientifically valuable.

But my great hope is that they'll actually use these freed-up funds to reach for something truly awe-inspiring. Landing humans on other planets, searching for (and possibly finding) life elsewhere in the Solar System, or perhaps even reaching for another star system... there are plenty of goals out there that we can shoot for that people will be excited for.

I'm simply reminded of the great artist Michaelangelo, and my favorite thing that he ever said,

The greater danger for most of us lies not in setting our aim too high and falling short; but in setting our aim too low, and achieving our mark.

So aim high, and encourage your local space agency to reach for the greatest heights that are out there.

I agree the Shuttle long ago stopped being particularly inspiring, nor has the ISS panned out. However, would Hubble have happened, to say nothing of lasting as long as it has w/o the Shuttle?

I do see a lot of work going into VASIMR drive. That would be cool, get us to Mars in 39 days give or take a couple.

Totally agree with you on this. Space developement was conspicuous by its absence and dissappointingly so. I hope, and optimistically think, that Obama (a self admitted trekkie of sorts) has a few tricks up his sleeve, such as allowing NASA to revert back to its original oversight position instead of actually trying to develope space itself, and I've heard talk to the effect that the next phase will see incentives offered to emerging space industries, like Burt Rutan and his collegues are developing privately, to play a larger role, and seeing NASA offering lucrative prizes for specific goals and achievements.

When I see that terrific space station from Kubrik's 200l Space Odyssey, in such stark contrast to the spindly, expensive and blatantly temporary arrangement of the ISS, I'm reminded that the big rotating space station concept was dependent on being able to put huge payloads into space economically, and at the time of its inception it was thought we'd be launching ships the size of 10 story buildings into space using (and using up) nuclear bombs to propell gigantic structures. Look closely at the cores of that awesome space staion and notice that the end sections look an awful lot like the designs for the Project Orion Nuclear Rocket Ship nose cones. National and international concerns over a strategy using exploding atom bombs like that doomed the plans even though the science supported it and the amount of radiation released would have been minor, and clearly the balistic missile approach, which was favored by the military as an ancillary and somewhat parallel developement to the overall defense program in the cold war, became the standard method, which worked well enough to prove the point, though clearly using rockets which had to be of such a size they could be carried on trucks around the country and hidden in silos, precluded gigantic rockets which were needed to be scaled-up for an economical program.

Robert Truax in the sixties had a concept for really giant rockets to launch millions of tons at once called "sea dragon' that instead of nukes would have used more conventional rocket fuel, lots of it, loaded into a sea-launched rocket (no need for special launch pads and all that so it would be cheap) built to be really durable out of strong steel and made to survive a return to the ocean after placing its million ton payload into orbit. The idea being that building a rocket capable of lifting a hundred times what a small ballistic missile could would not cost a hundred times more and because it was so durable and simple to build they'd be built at shipyards, like sections of submarines are but without all the expensive add-ons that submarines need, and towed out to a favorable location in the ocean. As it filled with fuel it would be partially submerged and pointing upwards, naturally, and pointed to the desired inclination for placement into its precise orbit.

Of course that would divert money from balistic missiles and be impossible to hide from enemy eyes.There was a high premium on secrecy then, youll recall. Keep in mind that NASA's genesis and operation is essentially DOD.

I still like that idea of the Sea Dragon but lately I've encountered an old idea made new that's under consideration for developement which will likewise make it cheap to get lots of mass (fuel for one) up into low earth orbit, called 'quicklaunch'. The physicist, whose background for 20 years of working with these kinds of super cannons in a practical and hands-on experimental sense, has a fantastic googletech lecture up on youtube that he gave to the folks at the Googleplex last December, so it still kind of new. Search for the term in youtube 'quicklaunch rocket cannon to space' and you'll see it. Oh..and price...$250 per pound, which is cheap by comparison and could go a lot cheapercheaper and still make money...and create some awesome high tech jobs. The drawback is that the payloads, each about a ton but capable of launching every 30 minutes, have to withstand 5000g, which fuel, water, shielding and hardened satellites can do just fine but people and delicate apparatus would still need a man-rated launch and so maybe the guys at Scaled Composites are those guys.

The developement, he states, would cost about $500million and take about 3 year to build.

But,of course, NASA as it stands now, has to keep its congressmen happy, and its army of engineers and techs in their career paths. Talk about inertia.

The idea that this Dr Hunter has is tanalizing and I have to wonder if some other emerging nation with a penchant for both prestige and profit wont leap-frog and jump on it. Nothing gets organizations motivated more than a little competition, and nothing has been holding us back more than the $10,000 a pound expense of getting the basic massive supplies of fuel and other stuff out of the gravity well. We need to get beyond the conestoga wagon stage and NASA thinks we simply need bigger and progressively more complex wagons,or so it seems.

Oh..and the standardized bullet shaped cylinders used as fuel containers (9' diameters I seem to recall) are designed to be remotely piloted and guided to join-up into a huge axially rotating assembly like a tinker toy and similar to the old school rotating space station so we'd have artificial gravity, shielding and all the fuel we could need with plenty of redundancy possible.

I can't help but notice that the first point on your list of disappointments also applies to the suggestions you give at the end of your post. Landing a human on another planet is definitely awe-inspiring, but it's not exactly a short-term goal. Another star system is definitely long-term. Searching for life is more of an open-ended (and expensive) question rather than a well-defined goal. Don't get me wrong, I'm all for the things you think NASA should become, but I have my doubts about whether the political incentive, public awe and support, and other circumstances that helped drive the Apollo program can ever be replicated. I have my hopes, too, but definitely doubts as well.

I am baffled that anyone expected this rumor to be addressed in the address. Even if it was a sure thing - I can't imagine Obama announcing it at a major media event. If Constellation is to lose its funding (likely), the announcement will be as low key as possible.

There's also the problem that what Obama personally believes and supports is almost irrelevant. The way the filibuster is used now means that the USA is, in effect, a constitutional monarchy but, unlike most constitutional monarchies, it doesn't have a functioning parliamentary government. Compounding this is the fact that most Americans still believe their president is a powerful figure and so don't understand the need to get to grips with the problem.

I don't see anything coherent, in space or anything else, coming out of the USA for a decade.

Thanks. Totally in agreement.

I tried to express the reasons why I am so consonant with you, but there were too many...and they were not by any means the usual ones, so I started to think about them: new reasons for space exploration and the fate of mankind!

Why the need for a extra-terrestrial Louisiana Purchase - so to speak - and what are the material and spiritual benefits? Pros and cons back and forth, so much that this comment lay inert for 20 minutes or more before I remembered it.

Not a bad way to start the day!

Thanks.

NASA has its own constellation? Why are they wasting money on that? Somebody should give them a rocket....

Whether or not NASA gets to keep that $1-2B per year depends on where that money actually came from - for example, was the bulk of it originally meant to keep the shuttle program running? We can't really keep the shuttles running anyway - except for Endeavor, which isn't even on the launch list, they are all past their design lifetime. It would be great if congress allows NASA to keep that money in the budget - wherever it came from.

Another thing congress needs to do is amend some of the post-WW2 and cold war rules so that NASA can contract foreign agencies to provide transport. Otherwise we have to pull out of the ISS and if we pull out I don't believe anyone else will continue to sink money into it (and it will be de-orbited before the original planned end-of-funding). The ISS may be pretty to look at, but I don't even have any idea what experiments (if any) they have conducted on board. With the shuttle I can recall using data from two programs (and I have this niggling feeling that I used data from another but I just can't think which one).

Personally I see no great issue with ending human presence in space for now; if anyone really wishes to consider a lunar base someone first has to lay down the foundations for survival and that alone can cost a fortune and take many years. As for any grand plans to stage a launch from low earth orbit, I just have to roll my eyes. Look at the great difficulties encountered with the ISS - and yet people expect to be taken seriously when they say we'll launch rocket parts which each weigh more than any component of the ISS and somehow assemble these parts in space, launch a crew vehicle and strap it onto the orbiting rocket, and then fire that off? Such a scenario would not violate any fundamental physical limitations but it is not practical nor can I see how it will accomplish any science not otherwise possible.

For now I think space scientists still have much to contribute by observing the earth or developing more orbiting astronomical and solar observatories.

The success of the non-manned missions and probes of Mars and other parts of the solar system is the way things should go for now. These programs have expanded knowledge of basic science and our understanding of the universe. I include the telescopes and other devices that are studying the deep universe. I agree that those costly programs with little end value (like Ares rockets) should be eliminated.

Personally, these are my 5 items for what is wrong with NASA.

1.) "The Gap" - the 7 yr period when we have noUS man-rated spacecraft to launch. NASA knew this was going to bite them in the nethers and they reacted poorly in managing/mitigating the impact.

2.) In producing Constellation, NASA has not been innovative, or as you put it "insufficient to take us beyond the Moon anyway". There is nothing cutting edge (read: awe-inspiring) about the vehicles' design, the Design Reference Missions, the capabilities of each vehicle (other the PTO tonnage) or the program life plan.

Translation - twisting a famous line: If you want to take my bucks, bring me BUCK ROGERS!

For instance, I want to see a vehicle that can used to space test the new technologies like VASMIR and other propulsive systems development AND carry out the space science on the same vehicle design.

If Constellation is not leaps and bounds better at collecting data than LRO, MRO, Cassini, etc. it's not worth the investment.

It's not.

3.) What NASA loses, JAXA, ESA, and the CSA lose too - Little known detail: If NASA has to (and it will) use ROSCOSMOS assets to get astronauts spaceborne, the agency will also have to foot the bill for partner space agencies who want to send their men/women aloft. (Augustine, 2009).

4.) According to the last GAO reports I think someting like $0.03 of each of my tax dollars goes to the agency. FACT: we spent MORE money on teachers for military dependent schools (DODDS) in 2009 that NASA did on Constellation - I can cited FOIA references to substantiate if asked.

If O'Bama were to allow NASA to create a charitable mechanism like the Combined Federal Campaign where Americans can pitch in to buy NASA what it needs, I'd be all for it! I'd pitch in $5 a month to get them going, as long as they can prove that money directly funds development of a new vehicle (that happens to not be the Constellation architecture).

5.) NASA does little to take their plight to the American people and explain how the paltry budget screws them out of doing the things we expect them to do. At the same time, unless you stream down NASA-TV (I admit, I do LOVE this channel) or regularly drill into their websites you're not going to know what's going on at the agency.

The agency needs to seriously consider spinning up an aggressive, organized PR machine that gets the public wired into their work. The current smattering of twitters, blogs and what-not are not a cohesive PR identity.

These are just some of the things that bug me.

~C

I agree with (6) about our dysfunctional government.

I'm not a rocket expert -or even a rocket buff, but I wouldn't dismiss a new design based upon a single figure of merit. There should be many figures of merit for a launch vehicle.

(1) Payload to low earth orbit.

(2) cost per launch.

(3) Reliability, what is the chance of losing the payload entirely -do you need to build a second satellite as insurance incase the first one is destroyed? What are the odds of missing your launch window because of an on the ground delay?

(4) Accuracy, how close to the intended orbit does it put the payload.

(5) Launch stresses, both static and vibrational on the payload.

I would think with modern technology and materials, we could do a lot better at this multidimensional optimization problem then we could in the 60s. I don't have an opinion on whether Ares is better.

I can't think of an exciting mission that requires manned flight -and is affordable enough to be politically feasible.

Good points, Ethan Siegel

I have read that a longer term rocket project replacing these is in the budget.

You wrote:

"The Ares rockets currently in development (Ares I and Ares V) are barely improvements"

Lets hope the next generation include many improvements.

In general, at this point robots seem a better investment than sending humans.

Regarding my previous, googled:

NASA Plans for FY 2010, Aeronautics Research

http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/345954main_7_Aeronautics_%20FY_2010_UPDATED_fin…

"... Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen) research and development (R&D) results to industry and government, and to expand development of key testbeds to

enable testing of integrated, system-level capabilities."

#14 of mine, nevermind, that's not space. It looks like air traffic control.

I respectfully differ with the author on this matter. I don't think that throwing away the large investment in a Shuttle replacement that is within a few years of flying its first mission and then giving more than $6 billion tax dollars to vaguely defined "commercial space" ventures amounts to nothing more than a wasteful, politically motivated reset of America's space effort. Besides, how can Obama's plan be called "commercial" when it transfers $6 billion in taxpayer dollars to companies owned by Obama supporters like Elon Musk. Sounds more like pork than a smarter way of dong space exploration. Besides, the companies that were building the Constellation rockets are independent, commercial firms in their own right.

Some comments given here reflect an ignorance of how the historical NASA/Industry outside contractor relationship works. It was a well-defined process that allowed NASA to do remarkable things like reaching the moon after less than 25 human missions. NASA has never built a rocket and the Constellation rockets saved billions of dollars by adapting a lot of existing Shuttle technology.

NASA has its own constellation? Why are they wasting money on that? Somebody should give them a rocket....

It was no stretch of the imagination to believe that, 30 years in the future... [things would be] like in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Oh yes it was. Apollo was a lunge to an "awe-inspiring short-term goal" -- but not a contribution to any methodical, sustainable development of human spaceflight. Could we get a dozen men on the moon and back safely at a cost of ~$2 billion a head (1969; ~$11B a head today)? Yes. Was it anything like what we'd have done if the goal had been to develop a robust, affordable way to access space -- orbit, the Moon, or beyond? Not really.

Ditto for STS: although it was billed as a sturdy, cost-effective "space truck" -- hey, a Shuttle, just like the jet from Logan to Laguardia -- it was also, in fact, a lunge. Nobody had built any reusable launcher or reusable re-entry vehicle (two different regimes with conflicting engineering requirements)... but in less than a decade, in one clean-sheet design leap, we were going to have both in one, suitable for all needs of NASA, DoD, and commercial space users. What we got was a hell of an engineering feat -- but also a costly, fragile hangar queen requiring so much highly $killed prep and maintenance that it was no cheaper per pound of payload in orbit than expendable boosters.

We pretended it wasn't so, and in 1984 promised ourselves a space station as if we'd solved the problem of robust space access and could move on. What we got was what you'd get if you built a mountaintop home with only a Formula 1 racer to carry lumber, bricks, workmen and groceries: lots of delay, cost growth, and de-scoping. ISS wasn't a bad idea per se, but just building it and maintaining it has eaten up almost all of the budget and astronauts' time so far. One more lunge: awe-inspiring in prospect, but...

Ethan, you're a physicist: do the math that Tsiolkovski and Goddard did. Given the gravity well we're in, the energy density of chemical propellants, and the temperature limits of workable engine materials, space access via rocketry started (and remains) in an extremely high-cost, low-volume corner of bleeding-edge engineering space. What leaves the pad is typically 85-90% propellant, 8-10% structure, and 3-5% payload in orbit -- significantly less if you bring structure back for re-use. If that's to become affordable, it can only be through far more design-test-fly-redesign iterations than we've ever seen or planned. Lots of boring materials development, lots of boring engine refinements, lots of boring unmanned trials, lots of launches pushing the envelope a tiny bit more, not many flags and footprints and ticker-tape parades.

That's the reality we resolutely ignored during Apollo, during Shuttle development, during ISS development, and in VSE->Constellation (which was a dead man walking the day Bush announced it in 2004). Space access is hard, and -- absent Magic Tech Breakthroughs -- getting good at it is going to be slower and more costly than almost anyone has been willing to face. It's more fun, and more politically saleable, to say "back to the Moon!" or "On to Mars!" than to acknowledge that we'll need to design and fly (and crash) as many times as, say, aircraft builders did between the Wright Flyer and the DC-3. (BTW, this applies to lean mean entrepreneurial New Space startups just as much as to allegedly bloated, stodgy NASA-Boeing-Lockmart. The idea that the former will deliver us to KubrickLand much faster through the magic of private enterprise is another awe-inspiring movie, just ideology-fiction instead of science-fiction.)

Yes, it was a stretch of the imagination to envision 2001 in 1969. Unfortunately, we've spent 40 years avoiding a clear-eyed look at the only real-world path between them, and looking for the Next Great Lunge instead.

Don't forget that the final design was the result of successive Congressional reductions to NASA's budget. The original shuttle was supposed to have two manned stages. That's right: the lower stage not only had wings, it was manned as well(iirc, initially, the upper stage had no wings.) With multiple budget reductions, NASA was forced to turn to DoD for additional funding. Of course, what DoD wanted - several thousand miles of cross-range in orbit, for example - wasn't exactly compatible with the original mission of being a low-key space truck that would ultimately be part of a much larger infrastructure.

What happened was completely predictable: having to be all things to all people, the Shuttle ended up doing none of them very well. Instead of the Willys Jeep, we got the Bradley Fighting Vehicle :-(

very interesting post, I have a blog on similar argument Fair Science Blog, go to visit it.

Bye

Rox Blog

That first stage itself, evaluated in Phase A and B during 1969-71, would have been a lunge. The designs were coming in with 12, 16, 24 and more engines, combining turbojets and rockets... heavier than a 747... reaching speeds 3-5 times faster than the SR-71 Blackbird... and oh yes, safely separating from a piggyback second stage at those speeds (can you say "hypersonic shock"?).

Anyone who tells you that could have been built in 1971-1978 -- on the STS team's original budget request or on any remotely possible budget -- is blowing smoke. Charley Donlan, the very smart program manager, said later:

"It wasn't till the phase B's came along and we had a hard look at the reality of what we meant by fully reusable that we shook our heads saying, 'No way you're going to build this thing in this century'... Thank God for all the pressures that were brought to bear to not go that route.'"

Agreed that the (DoD-driven) orbiter size, and delta wings for cross-range, made matters worse. But deeper than that was the hubris of aiming for an operational vehicle in one lunge, rather than facing the need for an X-series of technology development platforms, effectively open-ended in cost and duration. That's a hard sell to any Congress or private investor, then or now. Well... Challenger and Columbia were nature's way of telling us the Shuttle is an X-craft, whether we admitted it or not.

Because we'd reached and left earth orbit within a few years on the way to the Moon, we believed that reaching orbit with reusable hardware, routinely and affordably, should be easier than Apollo. In fact, it's much harder.

Just getting astronauts beyond low earth orbit will get some attention. The most cost effective method for doing so might be to develop an in-orbit refueling technique, as proposed by the Augustine commission. The second stage of the booster rocket could then be used to boost a manned capsule into a higher orbit. Using this technique, a manned capsule could orbit the moon or travel to the LaGrange points. Traveling a million miles from the earth might get a little attention, hm? If the capsule were enlarged into a true space craft, it could travel to near-earth asteroids or the moons of Mars.

Incidentally, I agree with the suggestion to create a space craft using Ad Astra's plasma drive. Hopefully the plan to put a drive on the ISS is still on.

I made this comment earlier, but it somehow didn't get through moderation...

You say "The Ares rockets currently in development (Ares I and Ares V) are barely improvements in any way over the Saturn V rockets from nearly half a century ago, even on paper!"

And then you display a picture of the relative heights of the Saturn V and Ares IV. Well, as you know, height is clearly not the relevant variable: lift capacity is. The Saturn V had a lift capacity (to low earth orbit) of 118,000kg. Ares IV will be able to lift 160,000kg. Now, the Space Shuttle can lift 24,400kgs to LEO, which means Ares can lift almost two Space Shuttle-loads more than Saturn. The heaviest-lift operational rocket in the world at the moment - the Atlas V HLV - lifts only 29,420kg. So Ares IV will be able to lift over 5 times as much as the most capable current rocket, and, again, just the difference between Ares and Saturn is bigger than the Atlas V's capacity.

@23 - Forget PTO numbers. You're looking at the wrong metric.

One of the BIG FACTORS that folks overlook when talking about sending rockets beyond Earth is weather. Mother Nature doesn't care enough to give us clear skies on every Launch Day. Because of the precise navigation required, missions to the Moon and Mars perceivably would not have the luxury of LEO missions to sit on the pad and wait it out.

Past experience shows us that cold weather and SRBs are not BFFs (Challenger) and yet, look at each Ares vehicle's design; the SRBs are still there. Only this time, the connecting O-ring gaskets are much bigger in this new version. As Astronaut Mike Mullane observed: (paraphrasing) the problem with Shuttle's SRBs is that they are just bigger versions of the old Chinese rockets used for centuries.

Once they are lit, THEY'RE LIT!

Now the Shuttle was configured into its chosen "stack" design to mitigate some (definitely not all) of the risk of being attached to over-sized rockets and a tank full of fuel (these are over 85% or more of any space vehicle's launch weight as we all know). Apollo's design had no SRBs and look at the safety record. Almost all Moon shots had some sort of guidance or engine-firing anomaly on launch and yet all rockets aimed at the Moon indeed made it there.

Highlights:

- Apollo 6 (non-Moon) had thrust fluctuations in S1C, S2 had motors cut-out and yet S-4B did a decent job of pushing to orbit even though it overused fuel.

- Apollo 12 got hit by lighting on the pad and on the way up.

- Apollo 13 had the faulty cryo-tank stirrer trigger a detonation which blew out a large portion of the CSM.

No 100% of crew or vehicle once the rockets lit up.

So which is better? Apolloâs first stage burned LOX and had good safety margins but wasnât reusable. Shuttle has reusable SRBs but a failure destroyed 1/5 of the fleet. Constellation/Ares vehicles look like Apollo but are children of the STS design.

IMHO: We should work on finding a way to make a reusable LOX powered stage or mixed-fuel configuration which improves safety margins.

Edit to my post #24...

No 100% 'loss' of crew or vehicle once the rockets lit up.

Clarifying one thought in post #24.

When I say the Challenger loss was 1/5 of the fleet, please remember that Endeavour was built _after_ the accident.

I have a fairly different perspective than most. I think that the fundamental problem is one of priorities. Most commenters want NASA to either wow us with some new, amazing accomplishment or to continue providing more and more science. I think that our first priority should be survival -- namely, to first establish an off-world, self-sustaining colony because we're going to be staring down the barrel of self-replicating technology by mid-century. Obama's decision means that a self-sustaining, off-world colony is now even more years away. For this reason I think that his decision is potentially very, very bad.

Chris, you make good points. If there are safety problems with Ares V, then that's bad and we need a better way of making it. But, clearly, a superheavy lift rocket is most certainly worth having. And Ares V - if it achieves the lift capacity advertised - will be awesome for a number of reasons. For one: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Technology_Large-Aperture_Space_T…

(I'm not a big fan of human spaceflight, btw. NASA should so science, not send people places).

Mike,

Good job bringing up ATLAST and discussing where we absolutely need to head science-wise. We absolutely need heavy-lifter which can boost big scopes like the 6.5m JWST and ATLAST "gigantic" 8m.

NASA is DIW. No vision, other than what Congress deems. Their funding is driving requirements, instead of making their requirements drive funding. Same issue as when the JFK failed to pass INSURV a few years ago.

Elon Musk was brought up, once. SpaceX now has it's own HLV on the drawing board, and is moving forward with it. Musk has a vision, and he is paying for it. I see him spending his profits from his new contract with NASA on developing the HLV and going forward with his plan of colonizing Mars, on his own.

And it won't cost $50 billion. NASA's lack of vision, drive and innovation will end up costing them far more than they could have requested from Congress.

Go for more robotic missions! To those who claim it isn't as awe inspiring, remember Hubble, remember Spirit and Opportunity. Results speak for themselves whether collected by a man or a machine.

Space just is such a hostile place for man, and if we should go there it's nice if we have had a bunch of robots building habitats first anyway: "Welcome to Mars. Would you like a cup of tea and a hot bath, Sir?"

I agree with Thomas. The key is robotics. The sheer logistics to support a human for a long term mission make it prohibitory for our current logistics support model.

But with robotics, we gain a greater level of freedom.

For what it's worth, I've always been a bit disappointed with the ISS also. So clunky, so unaesthetic.

My general thoughts in this area..

The big step in space exploration - manned, unmanned, whatever - is the first step to Earth Orbit. If we can reliably deliver large amounts of mass to orbit, everything else - including missions to mars - becomes a fairly simple matter of engineering.

So I'd suggest a two pronged approach. For relatively fragile loads (such as Humans), we will still need rockets for the forseeable future -at least until the space elevator is built. But for the majority of loads (Food, Water, Fuel, Construction materials, etc), other approaches should work just as well. For example,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_gun

A WWII-era 16 inch gun was adopted to shoot to an altitude of 180km. And bear in mind that these guns could fire a fairly complex object (i.e. a fused, composite 16-inch HE shell), accurately, perhaps 20 miles in wartime.

Plus, if bulk materials can be delivered by a separate method, and in near-unlimited quantities, then the human-carrying rocket can devote more payload to both people and safety equipment.

Eventually, of course, you would hope to nudge an Earth crossing asteroid into orbit around the Earth - find one of the correct composition and you can basically build everything you want out there. There could be health and safety issues with moving trillion tonne asteroids about, I admit..

But the approach of trying to put everything into space on chemical rockets will never be cheap, and will always mean compromises.

As an aside, the argument that a later source stuck that sentence about Sirius being red in Ptolemy's work after reading Horace or Aratus (both poets) and deciding that Sirius belonged in that list of red stars as well is possible. However that assertion is impossible to confirm or refute, so it isn't talked about among scientists. www.i-tunes.com/download

Thanks for the post. Straight Out Question: Are you aware of any factual source that actually details how far behind the Constellation program is? President Obama, as well as several directors for NASA, has gladly publicly announced that Constellation has fallen behind. However, I find it difficult to weigh whether Constellation is so far behind that we need to end it if I do not know how far behind it actually is (keeping in mind that Obama's new direction would need to compensate for the $9 billion we've already invested into it). A common question is, "Is constellation worth continuing when it is so far behind?" A more uncertain question is, "Is it so far behind that it's worth a $9 Billion dollar deficit?" Albeit NASA would naturally srap the program to obtain all the worth they could from what has been accomplished thus far, they would be losing most of the $9 Billion.