"April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain." -T. S. Eliot

Of course you all know the refrain, "April showers bring May flowers," but there's one April shower that brings fireballs instead: the Lyrids!

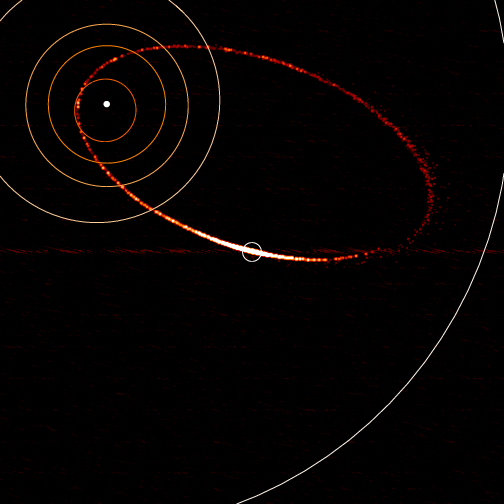

Like all meteor showers, the Lyrids come from a comet's dust trail that forms a great ellipse with respect to our Solar System. Once per year, the Earth, in its orbit around the Sun, passes through this dusty debris. When this happens, the Earth, moving at over 10,000 miles-per-hour with respect to these dust grains, cause the dust to vaporize in a fiery plunge as they collide with our atmosphere.

Every year, right around April 22nd, this meteor shower peaks, delivering anywhere from 10 to 100 meteors per hour visible beneath dark skies.

"Why is there so much variability," you ask? Well...

These dusty debris trails that fill our Solar System all come from comets. When a comet passes close enough to the Sun, it spews off gas, dust and ions, leaving an elliptical trail in roughly the same orbit as the comet itself. But comets spend most of their time far away from the Sun, so that these big bursts of debris only get emitted at rare intervals.

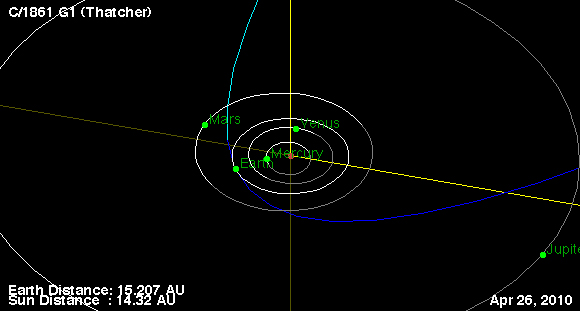

Are we going to pass through one of these big bursts, or are we going to spend this year passing through a lull in the debris trail? Like every year, we never know until we get there. The Lyrid meteor shower is a particularly tough one to predict, because the comet responsible for it, Comet Thatcher (after the 19th Century astronomer, not the 20th Century Iron Lady), is not only perpendicular to the plane of our Solar System, it also has a disturbingly long period of 415 years, meaning it won't be back until 2276!

But the comet isn't the interesting thing: the dusty debris which brings us the meteor shower is! The peak of the meteor shower, which is the best time to observe it, should occur close to midnight in North America during the night of April 21st / morning of April 22nd, making it the perfect way to usher in Earth Day!

No matter where on Earth you are, here's where you want to look.

The bright star Vega, the fifth brightest star in the night sky (and #2 in the Northern Hemisphere), should be high enough in the sky by 10 PM to easily identify it. (Vega features prominently in my summer sky tutorial, here.)

There's a small (but prominent; visible even in most cities) parallelogram nearby, just slightly closer to the horizon. Combined with Vega, that's how you can easily identify the constellation Lyra. The meteor shower should originate just a few degrees away, to the upper right of the parallelogram. But don't look directly at that spot, and don't use a telescope! The meteors originate from there, but you'll see them streaking away from that point, in random directions!

Over the course of an hour, you should see anywhere from 10 to 100 meteors, depending on how good this year's Lyrids are. You'll have the added bonus of a moonless sky; the waxing crescent will be so minuscule that it will have completely set by time the constellation Lyra is visible. The meteors themselves are worth the price of admission, but every once in a while, the Lyrids give the gift of a true fireball: a meteor so bright it outshines the entire sky combined, lasts for a few seconds, and can even cast prominent shadows.

No promises, of course, as it's impossible to predict these things, but if I've got clear skies, you can bet I won't miss the opportunity to spend some time enjoying the wonders of the night!

For those of you who want real-time updates on the Lyrid meteor shower, including reports from around the world as they come in, well, what's the point of running the best Science news service on the web if you can't make that happen? So follow the Meteor Showers & Comets trap and stay on top of it. However you do it, make sure you enjoy the show Saturday night and into Sunday morning, and know that my eyes and millions of others will be gazing upwards with you!

Awesome info. Cary on ;-)

Damn and blast. After several weeks of clear night skies, it chose to cloud up and rain on the night of the Lyrids.

Hear anything about California's fireball? One idea has it that this kind of meteorite might come from a comet's nucleus. It'd be interesting to know if it's from the stream.