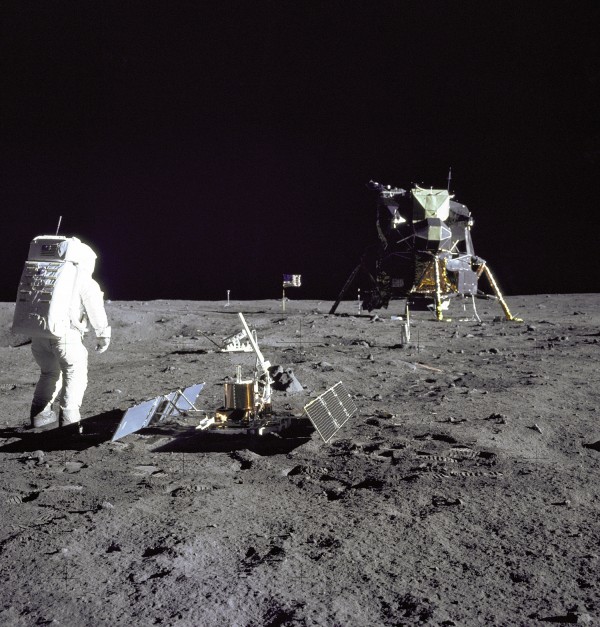

"The achievements of Apollo were so bold and our subsequent efforts so timid that the energy of those years seems like a youthful dream." -Buzz Aldrin

43 years ago today, humanity took our first steps on another world, venturing nearly 400,000 kilometers from home and walking on the surface of the Moon.

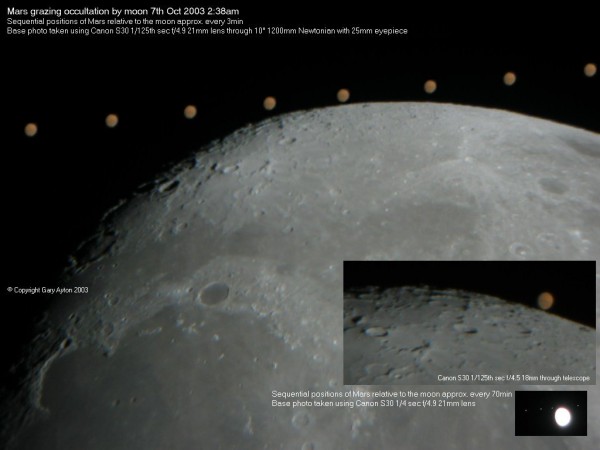

Of course, what we found there was a world whose soil was very similar to our own, but devoid of any atmosphere, liquid, or signs of life, present or past. But out beyond the Moon, visible in the distance even when viewed from Earth, lies a world that's excited our imaginations for generations.

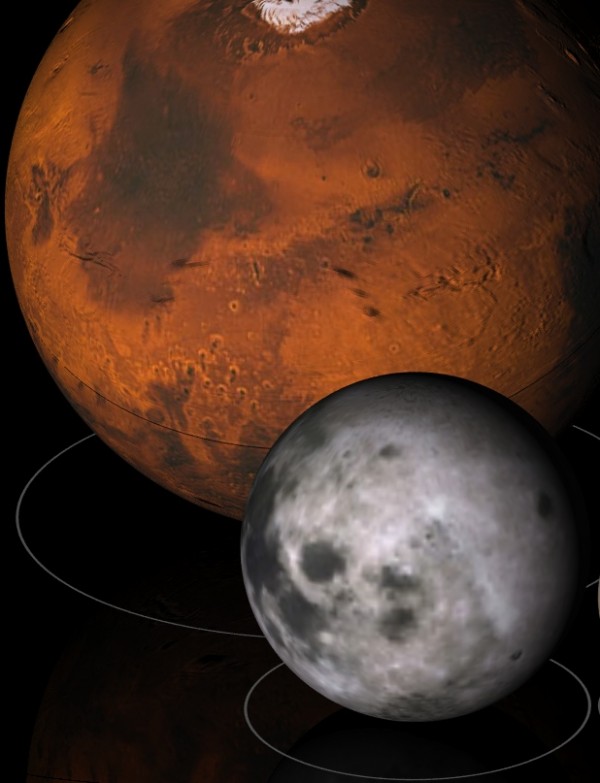

Despite its tiny appearance, Mars is much larger than the Moon in terms of actual size. It only appears smaller because it's up to 100 times farther away from us than the Moon is; if you were to put Mars and the Moon next to one another, the differences would leap right out at you.

Unlike our dry, desolate, airless Moon, Mars has an atmosphere, polar icecaps, and plenty of hope that it once had a watery past. It made all the sense in the world, once we'd made it to the Moon, to set our sights on Mars.

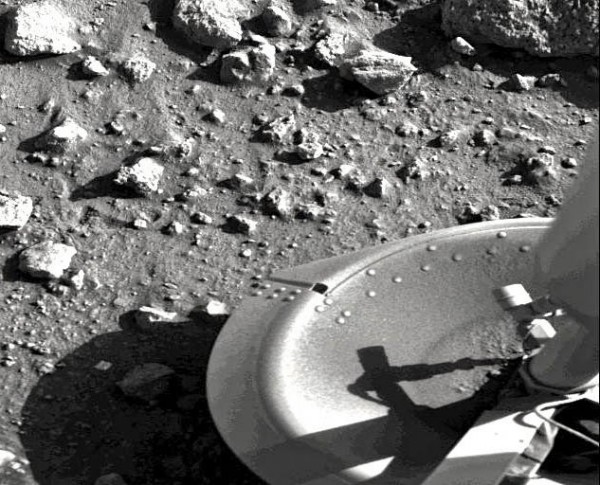

While -- as you well know -- we've never sent a manned mission to Mars, it was exactly seven years later, on July 20th, 1976, that we landed our first spacecraft safely on the surface of Mars. Here's the first (black-and-white) picture of the Viking 1 Lander on the surface of the Red Planet, photographing its own footprint.

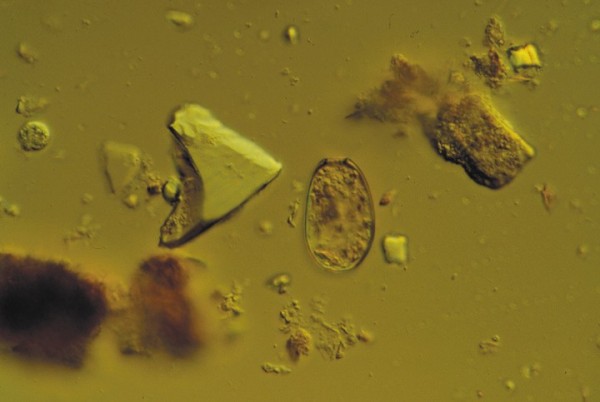

One of the most ambitious things the Viking landers were equipped to do was to look for signs of life. One of the experiments, in particular, was really interesting. What they did was they scooped up some martian soil and placed it in a chamber filled with a liquid, nutrient broth.

The hope was that, if there were any martian microbes in the soil, they'd react with the nutrient broth, giving off organic gases that Viking would be able to detect.

Both Viking landers (1 and 2) performed this test twice: once with freshly-scooped-up soil, and once with soil that had been "sterilized" by heating it to high temperatures.

If there were microbes in the soil, you know what you'd expect to find: microbes reacting with the broth, giving off organic gases (carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen-rich gases) in the fresh soil, and none in the sterilized soil.

And -- believe it or not -- that's exactly what both of them found.

So, does that mean there's microbial life on Mars, just waiting for a drop of nutrient-filled Earth water to begin organic reactions? Or does that mean the original Viking spacecrafts were contaminated with Earth-based bacteria, and only after the sterilizing heat were we truly examining martian soil?

The other two tests that Viking did for life/organics came up negative, and so at this point, we have to say we can't know for certain. But we'd love to find out, wouldn't we? Well, since the successes of Viking 1 and 2, we've tried many times to land on Mars.

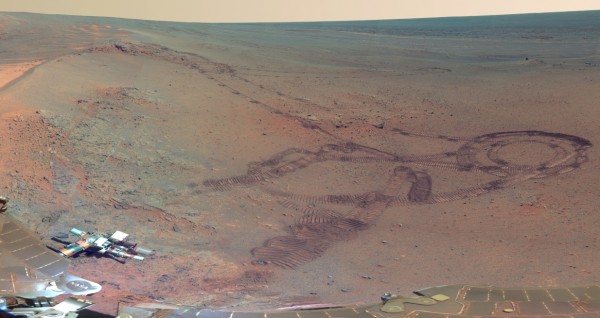

Although there have been many failures, including Mars 6 and 7, Mars Polar Lander, the Beagle 2, and Fobos-Grunt (which sought to land on the Martian moon Phobos), there have also been four more successes: Mars Pathfinder, Spirit, Opportunity, and most recently, the Phoenix lander.

And while we've done some amazing science on the Martian surface with these four landers, we've not only been unable to successfully test for present or past life, we haven't even sought to test for organics in the soil with the other landers.

But in just a couple of weeks, all of that is going to change, depending on how a very important seven minutes goes.

Mars Curiosity, the giant rover depicted on the right, is (arguably) the most advanced robot ever built. An entire science laboratory is on board this rover, which dwarfs Opportunity (whose clone is on the left) in size, speed, and scientific power. Because, among other instruments, know what Curiosity has on board? From wikipedia:

Sample analysis at Mars (SAM): The SAM instrument suite will analyze organics and gases from both atmospheric and solid samples. It is being developed by the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the Laboratoire Inter-Universitaire des Systèmes Atmosphériques (LISA) of France's CNRS and Honeybee Robotics, along with many additional external partners. The SAM suite consists of three instruments:

- The Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (QMS) will detect gases sampled from the atmosphere or those released from solid samples by heating.

- The Gas Chromatograph (GC) will be used to separate out individual gases from a complex mixture into molecular components. The resulting gas flow will be analyzed in the mass spectrometer with a mass range of 2-535 Daltons.

- The Tunable Laser Spectrometer (TLS) will perform precision measurements of oxygen and carbon isotope ratios in carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) in the atmosphere of Mars in order to distinguish between a geochemical and a biological origin.

The SAM also has three subsystems: the 'Chemical separation and processing laboratory', for enrichment and derivatization of the organic molecules of the sample; the sample manipulation system (SMS) for transporting powder delivered from the MSL drill to a SAM inlet and into one of 74 sample cups. The SMS then moves the sample to the SAM oven to release gases by heating to up to 1000 oC; and the pumps subsystem to purge the separators and analysers.

The key, of course, is whether the first-of-its-kind landing, on a world many millions of miles away, will succeed or not. Well, you don't have to wait much longer: on the night of Sunday, August 5th, Curiosity will enter the Martian atmosphere and descend, attempting to land safely and softly on the alien world below. Landings on Mars historically have about a 50% success rate, so everyone watching ought to have their hearts in their throats.

And what's going to happen? You don't have to rely on my explanation for it; NASA and JPL have put together a brilliant five minute video explaining exactly what this seven minutes of terror is all about!

My local planetarium will be broadcasting the landing live: will you be watching? In the meantime, for now, for the time leading up to August 5th, and for the days and weeks afterwards, I've built a spectacular trap on Mars for you, where all the news stories from around the world surrounding the red planet will be on display. (Got an iPad? I've got the brand-new #1 free news app for you to follow this story here!)

Image credit: The Mars trap via trapit, http://trap.it/.

It's no secret how much I've loved the Opportunity rover, and we've got a chance with Curiosity to absolutely blow away everything we know about the surface of our rubicund neighbor. I'm hoping for a successful landing, and I can't wait to see -- literally -- what Curiosity uncovers.

August 5? Well it's a LITTLE late, but you can still see it as an awesome birthday present!

Great post (as usual). I wasn't aware of the August 5 date, but now I am.

Let me use your comments section to ask a totally off-topic question: is there any way to communicate with the SB people to make suggestions about their new not-so-improved site? I've tried several times via the "contact us" link, and never gotten so much as an acknowledgment. If there's some way to do this, feel free to contact me directly, or post here in comments, as you wish. Thanks.

Why don't they include a microscope on any of the landers? Wouldn't it greatly simplify the search for life on Mars?

Great post. It's really impressive to see how difficult and complicate is to land a rover on Mars.

What I am curious about is, did they use the same landing technique for the previous rovers? If not, does anyone know what is the difference?

Cheers

@ Chris

That's a good question. I don't know for sure, but I don't think you can just point a microscope at some dirt and see microbes. The only time I've ever seen bacteria through a microscope have been either in carefully prepared slides or in a petri dish where they had been grown. Either way, separated from any opaque objects. I think if we had a way to automatically sort bacteria from soil to make slides then it would make sense.

At the very least, if a microscope was a feasible way of finding bacteria then I'm sure someone would have thought of it.

@ Filip:

This one I know! This is the landing on Mars to attempt the rocket-tether method. So add that onto everything else and you can see why 'seven minutes of terror' is an apt name to describe what it will be like for the folks at NASA/JPL.

Spirit and Opportunity were landed with the airbag method: housed inside a shell that was covered in airbags, they were simply dropped onto Mars. There was at least one before that, which served as proof of concet. Curiosity is unfortunately too heavy for that method.

Phoenix and others were landed with rockets on the landers themselves. It seems they expect to be able to get a lighter landing from this method, and they'll definitely end up with a lighter rover.

Though possibly a flatter one, too. I'm bitting my nails. I'm very excited about this. =D

* This is the first landing (sorry)

Very nice science and engineering.

"Curiosity is scheduled to land at approximately 10:31 p.m. PDT on Aug. 5 (1:31 a.m. EDT on Aug. 6)."

www.nasa.gov/mars has a countdown clock to landing on Mars.

And when you say your local planetarium will be broadcasting "live", of course that is "as live as possible", given the distance between Mars and Earth. Before we even hear that the spacecraft has touched the top of Mars' atmosphere, Curiosity will have reached the surface - one way or another.

@ Joffan:

That's what "live" means -- Every "live" presentation is limited by the speed of light, and most things you aren't witnessing yourself are transmitted slower than that.

Still, it's fun to think about the fact that the lander is so far away that the delay isn't just noticeable but downright nerve-wracking. :)

Great, if sad, quote from Buzz. But lunar soil was "very similar to our own"? Ummmm... no. Earth soil has organics and water, for starts. Lunar "soil" (regolith) is composed largely of shards of broken glasses and minerals that have been smashed and re-smashed, melted and re-melted from countless impact events. This process is part of why most plants and even bacteria can't grow in lunar regolith (unlike Earth soil): any nutrients are locked up in tough minerals... The list goes on, but lunar regolith is quite different than soil here on Earth.

Separately, before we get too wrapped up in space fanboy glee:

Let's remember that this $2.5 billion, over-budget thing is TWO YEARS LATE getting to Mars, the managers having missed the previous Mars launch window. (Recall that Alan Stern, of Pluto probe New Horizons fame, quit NASA after being overruled on cancelling this program to preserve other space missions that had remained on time and within budget.)

We already had a durable rover design (the MER - Spirit and Opportunity) and a proven delivery system. We could have duplicated them and explored more areas of the planet - and very probably met that launch window. But we had to go to the expensive Martian SUV with the precision rocket pack that will hopefully land successfully and let us more capably explore ... ONE site on the planet. It's a one-off design too expensive to fly again, with a nuclear power source using a plutonium isotope in rapidly-dwindling supply.

Enjoy the Mars pics. They'll likely be the last for a while, thanks in no small part to the juggernaut Opportunity, that has rolled over so many other opportunities.

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/06/msl-costs/

Look at the two new reactors being built, greg.

How many billions over budget and how many years late?

And how late are you to this thread?

If we're going to use lateness to measure failure, epic fail there, greg.

Wow, just wow, Wow. I've written about this previously elsewhere (the industry paper Space News, for one).

The "epic fail", as you put it, will hopefully not be a new $2.5 billion crater on Mars. I feel confident Opportunity will set down okay, people will become enraptured over great pictures and data - and forget all about the cost this Super Rover cost us not just in dollars, or even other worthy space projects, but the future of a sustainable Mars program itself.

What is supposed to be imparted by "I’ve written about this previously elsewhere", Greg?

You've written it twice, so what? If you write it 100 times, it doesn't get any more (or less) right.

And sod a sustainable mars program. We haven't got a sustainable moon program.

And where has all this "oh, it's over budget" gone? It's disappeared because it was pointless. You're right to remove it, since it doesn't make a point, just whines.

Greg, you seem to be getting Opportunity and Curiosity confused. you talk about Opportunity as the proven design, but then talk about how you're confident it will set down and talking about how Opportunity has rolled over other opportunities. Which would be great wordplay if that was the name of the rover you were criticising. :P

Curiosity, if successful, will deliver a ton more science than more Opportunity-style rovers. Which themselves delivered far more science than another Sojourner rover, about which the same statement could be made: Why make Spirit and Opportunity when Sojourner was a proven design? Because we want to move forward.

If you want to finger a NASA project as a waste that is killing other good projects, try the SLS. Nothing but a pork barrel and vastly more expensive than the rovers.

"Wow" - You said my "epic fail" was that I was late to the thread, but I wrote about this shortly after they missed their original launch window deadline. So that's what. And I'm of course I'm completely right in both cases. :P

CB - Yeah, you got me. I realized my error a while after posting. These spacecraft names are starting to become interchangeable. After "Cosmonaut", "Astronaut" and "Taikonaut", a better name for this craft would be "Juggernaut".

I did mean we should have reused the Opportunity design. We could have duplicated it and improved it - maybe a smaller RTG and improved instruments - to explore a lot more interesting places.

The SUV upsizing has backed up the robotic Mars program against the wall. We'll never fly such an expensive thing again, it's hard to see us going back to more modest ground explorations, and the outrageous overruns and mismanagement on Curiousity and JWST mean not much else is going to be happening.

There's $2.5 billion riding on that one landing. And then ... we hopefully get the tons of data you mention on that one location on the planet. And then not much else for a long time.

Debating SLS is just another big rabbit hole. Human spaceflight doesn't have a place? Commercial launch providers will be the salvation of NASA? An open question is whether SLS will survive for very long to begin with.

And by "smaller RTG", I mean smaller than Juggernaut's, er, Curiousity's. Something for nighttime heat and a bit of additional power for survivability.

Greg, you need to go back to school and take remedial english.

I said, and I quote

And how late are you to THIS THREAD, greg?

You've just upped the epic, greg.

Fail hard 2: Fail harder.

Yes, we'll never fly another expensive mission because this one had cost overruns. Just like we never launched this mission after the last expensive mission with cost overruns. That makes a lot of sense.

We don't go for more modest missions because we have immodest goals. If modest replication of previous work was the goal we would have continued launching Pathfinder probes and never made Spirit and Opportunity. But because those two have become a sort of 'default' for Mars exploration, it doesn't occur to you to wonder if the same reasoning doesn't apply to them even when the question is asked.

If MSL is successful, it will become the 'default' and someone will ask the same question about the next rover that does even more. If it is unsuccessful, it will be another unsuccessful Mars mission that didn't stop future missions from being planned and executed.

You're making a lot of completely unwarranted assumptions to come to the conclusion that one way or another this is the last Mars mission.

JWST's overruns can be laid primarily at the feet of Congress for not giving them the money they needed when they needed it. Nevertheless, we will launch more telescopes in the future.

And on that note: The only question for which SLS is the answer is "How can I keep that sweet, sweet Shuttle Program pork funneling into my district?" The impact of the pork launcher on NASA science is ridiculously greater than the impact of an expensive rover.

They can also be lsid at pork barreling.

The efficient choice is removed so thsat the money will be spentin politically advantageous ways to enrich private companies in states with the senators ear.

When did Hans Zimmer start working for NASA?

"Or does that mean the original Viking spacecrafts were contaminated with Earth-based bacteria, and only after the sterilizing heat were we truly examining martian soil?"

IIRC, the contender for best explanation was that it was merely a new soil chemistry.

O2 is given off when you split H2O...