"I am undecided whether or not the Milky Way is but one of countless others all of which form an entire system. Perhaps the light from these infinitely distant galaxies is so faint that we cannot see them." -Johann Lambert

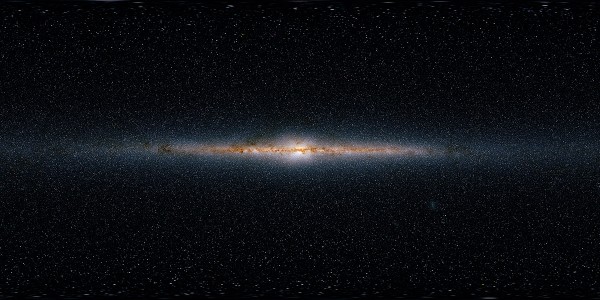

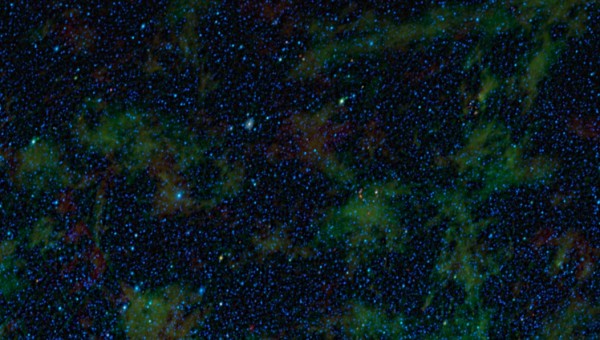

When we look out at the Universe, our view is pretty consistently dominated by the stars within our own galaxy. Although we know that many interesting things lie beyond -- globular clusters, individual galaxies, and rich clusters and superclusters of galaxies -- being in the Milky Way makes it very hard to see beyond it.

The plane of the Milky Way itself dominates a large portion of the sky. What appears to be a white streak is actually the light from billions upon billions of stars whose light appears to blend together from our point of view, while the dark nebulae are actually neutral clouds of gas-and-dust that appear in the foreground, blocking the light that comes from behind.

For a long time, the plane of our galaxy prevented us from seeing what lied beyond it. Termed the Zone of Avoidance, the Milky Way blocked some 10-20% of the night sky from view. While we were discovering a plethora of objects beyond the galaxy in all other directions, surveying the portion of the night sky that was blocked by our own galaxy was prohibitive. The light-blocking power of the intervening matter -- known as extinction -- was simply too much to overcome.

And this would still be true if we confined ourselves to the light that our own eyes can see. Thankfully, however, we now know better.

This was the very first picture of the entire sky taken in the infrared, thanks to the COBE satellite's DIRBE instrument. (And yes, the "IR" in DIRBE stands for infrared.) An even sharper view -- in more wavelengths -- has been provided by the two-micron all-sky survey (2MASS), as you can see below.

As you can tell, the light-blocking gas and dust has practically disappeared, and that's no coincidence. The wavelength of light that interacts with something is highly dependent on the size of the object itself. For dust grains in our galaxy, visible light is easily absorbed while infrared passes through uninhibited.

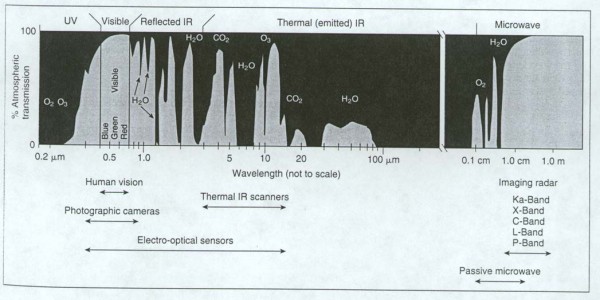

Image credit: retrieved from Tracy DeLiberty of U. of Delaware, via http://www.udel.edu/.

Image credit: retrieved from Tracy DeLiberty of U. of Delaware, via http://www.udel.edu/.

But for our atmosphere, the converse is true: visible light passes through easily, while infrared is more easily absorbed. That's why, to really get a handle on what's out there beyond the plane of our galaxy, we have to go to space.

The warm gas actually leaves an infrared signature, as seen in green from this all-sky mosaic in the infrared from WISE. What's really interesting, though, is that even with the warm gas, we can still find out what lies behind a large amount of the galactic plane from a survey like this. In fact, if you zoom in on the region marked IC 342 up there, you'll find a number of really interesting features.

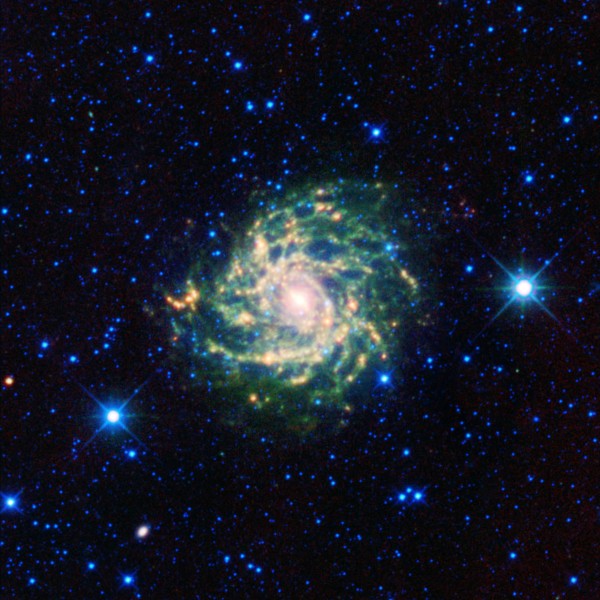

For starters, IC 342 is itself one of the most interesting objects in the night sky. It should come as no surprise that Andromeda is the largest galaxy outside of our own as seen from our vantage point, followed by the Triangulum Galaxy, M33, which also lies within our local group. But what might surprise you is that the third largest galaxy as seen from our location is actually this rarely-seen galaxy, IC 342, which wasn't even first seen until 1895!

Of course, when it was discovered in 1895, there were no infrared telescopes, and there certainly weren't any space telescopes. This galaxy can be seen in visible light, it's just very dim, and partially obscured. Even the Hubble Space Telescope, for all its power, can only obtain an image that pales in comparison to the infrared shots we can take.

Not only does the dust obscure the visible light, but it makes it extremely dim. If the Milky Way weren't there, not only would this galaxy be bright and prominent, but it would also quite probably be visible to the naked eye, even though it lies far beyond the local group at an estimated 10 million light-years distant. (About five times as distant as Andromeda.)

And what's maybe even more interesting is that there are tons of galaxies in the Zone of Avoidance that we just missed, for centuries, because of this problem.

Nearby IC 342, in the same region of the sky, you can see two prominent galaxies shining through some of the warm dust of our own Milky Way. If we zoom in, you can see a distorted spiral galaxy and a giant elliptical in far greater detail.

These galaxies are named Maffei 1 (for the elliptical) and Maffei 2 (for the spiral), after their discoverer, the Italian astronomer and infrared pioneer, Paolo Maffei. These are two of the intrinsically brightest galaxies close by, and in fact Maffei 1 is the single closest giant elliptical galaxy to us in all the Universe.

And yet, they weren't even seen for the first time until 1967.

More than 99.5% of the light from these galaxies are obscured by the intervening Milky Way; if not for our unfortunate galactic orientation, Maffei 1 (above) would definitely be visible to the naked eye alone! Although Maffei 2 wouldn't be, it's still gorgeous and worthy of study in its own right, and so different in the visible as compared with the infrared!

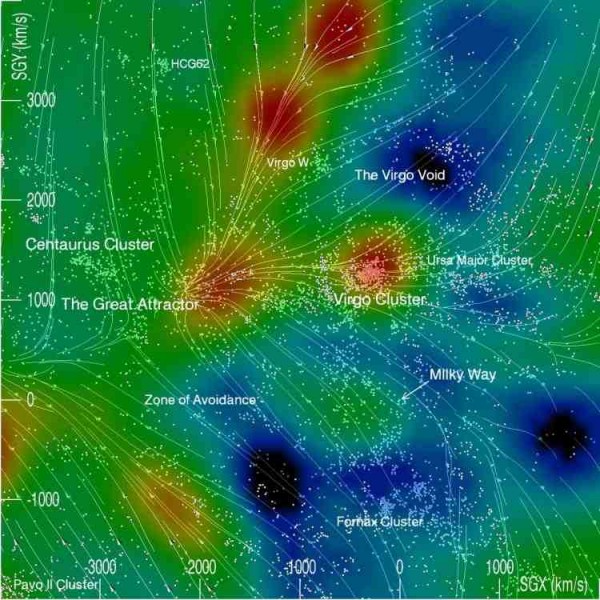

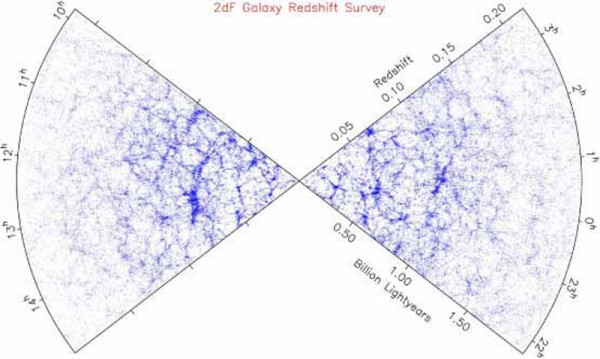

So if you were asking yourself what the Universe really looks like, and you saw this image (below), don't be fooled.

Image credit: Cosmic Flows Project/University of Hawaii, via http://www.cpt.univ-mrs.fr/.

Image credit: Cosmic Flows Project/University of Hawaii, via http://www.cpt.univ-mrs.fr/.

The Zone of Avoidance isn't a nearby region with very few galaxies, it's most probably a region with just as many galaxies as the rest of the Universe that just happens to be hard to see from our vantage point!

But the detailed observations of Maffei 1 teaches us something incredibly valuable. You see, there's a myth going around that if you -- a human being -- were placed at a random location in the Universe, outside of a galaxy, you wouldn't be able to see anything. Not a single star or galaxy would be bright enough to capture with your naked eye.

That's not true. While it is true that there are some locations -- like in the middle of great, cosmic voids -- for which you wouldn't be able to see anything, galaxies like Andromeda, Bode's Galaxy and Maffei 1 are abundant enough and spread out enough that the odds are at least one such galaxy (and more than that, on average) would be visible to you from any random location.

So if you want to see what lies beyond our galaxy -- or any dusty galaxy -- just look in the infrared, and watch the Universe open up to you!

It should come as no surprise that Andromeda is the largest galaxy outside of our own as seen from our vantage point, followed by the Triangulum Galaxy, M33, which also lies within our local group.

The Magellanic Clouds whimper softly in the corner of the room, ignored by all.

They're a bit small as dwarf galaxies to be among the largest galaxies in our local group, mind, so they should man up and stop whining..!

Ethan,

in this image that you posted from WISE: http://img5.imageshack.us/img5/3899/hxns.jpg

what is that? Is that gravitational lensing.. or? Just seems an unusual shape. Or is it just gas?

p.s. don't mean the green stuff :) mean the almost circular shape behind it, also seems to have a line below it.. like a tuning fork of sorts..

Coincidental alignment of background stars, nebulae, and galaxies? Doesn't look like lensing to me, but what do I know.

CB, you're probably right. Just caught my eye.

That's the problem with the eyecrometer.

It's chock full of errors.

Rumour scotched...! Anyone know the max (naked-eye) viewing range for a typical galaxy?

The biggest limitation is the areal intensity. Triangulum is very bright at ~6th Magnitude, but subtends half a degree and you'd be hard put to see it on any night by telescope.

Light pollution also cuts that down a lot and the moon's brightness will raise the brightness of the sky beyond the discernable limit of contrast.

If you're interested, get The Sky Observers' Atlas, ISBN 978-0-387-48537-9. It gives the visibility as contrast values for extended objects.

How can we have pics of our Galaxy its not like someone is out there and took a pic to show us what it looks like. Is it just a computer simulated pic of what we think it looks like ??

The first two pictures are, it appears, the Andromeda Galaxy, not our own.

However, the next two are our galaxy.

Note, the three following are us too.