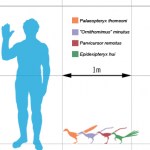

Steve Sweetman and I have just published a paper on a new maniraptoran theropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Wealden Supergroup of East Sussex, England (Naish & Sweetman 2011).

As you might know if you're a regular reader, much of my technical work has been devoted to Wealden theropods and I publish papers on them fairly regularly (recent articles: Benson et al. (2009), Naish (2010); see links below). I still have yet to publish one of my most significant contributions - the monographic description of the tyrannosauroid Eotyrannus lengi (the follow-up to the rushed and…

I've long had a special interest in the sleeping habits of small birds. In fact, as you'll know if you read the article I published here back in September 2008*, I've covered this issue before. In that article, I noted that at least some passerines secrete themselves away in crevices or thick foliage. I first became really interested in this subject after making one of my greatest natural history 'discoveries': a sleeping Blue tit Cyanistes caeruleus that I encountered while it was tucked deep beneath the broken bark of a tree, just the tip of its tail betraying its presence. I didn't have…

It's a sad fact of life that, as long as there are aircraft, and as long as there are birds, there will be collisions between aircraft and birds. I did in fact cover the issue of bird-strikes back in January 2008, but since then I've learnt a few new things that I'd like to share.

For the record, I'm not covering this issue - or featuring the various photos you see here - because I regard it as at all amusing or frivolous; quite the contrary. As I said in the 2008 article, bird-strikes pose a serious hazard to aircraft, most typically during landing and takeoff, and they also result in…

During the June and July of 2010 I and a host of friends and colleagues based at, or affiliated with, the University of Portsmouth attended the Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition. As you'll know if you saw the articles and pictures I posted here at Tet Zoo, our research group set up and displayed the extremely popular Dragons of the Air exhibition. Devoted to the study of pterosaurs, it had an indoor component but also featured several life-sized, walking and flying azhdarchids.

Many people noted here and elsewhere that it would be neat, and appropriate, for these models to form part…

I love seeing tetrapod-themed art, especially in unexpected places. While in London recently I noticed this 'tropical bird' painting on a piece of wooden boarding, erected to conceal building work. As you can see (larger version below), the work is mostly a brilliant montage of birds-of-paradise (properly Paradisaeidae), the remarkable resplendent "rainforest crows in fancy dress"* of New Guinea and its surrounds.

* Sherman Suter, 1998.

I'd prefer it if it was birds-of-paradise only, but it also features a few parrots (right at the top) and a Great blue turaco Corythaeola cristata too. The…

If asked "Why do giraffes have such long necks?", the majority of people - professional biologists among them - will answer that it's something to do with increasing vertical reach and hence feeding range. But while the 'increased vertical reach' or 'increased feeding envelope' hypothesis has always been the most popular explanation invoked to explain the giraffe's neck, it isn't the only one.

In 1996, Robert Simmons and Lue Scheepers argued that the giraffe neck functions as a sexual signal: they said that the necks of males are bigger and thicker than those of females, that the necks of…

On March 14th 2011 National Geographic screened episode 1 of their new series Wild Case Files (here in the UK, the episode was screened on April 11th), and the reason I'm writing about it is because I featured in said episode.

The first section of the show was devoted to an investigation of the 'Montauk monster'. They provided a potted history of the whole 'Montauk monster' story, spoke to all the main characters involved, and ended with me explaining how the carcasses (both the original, July 2008 specimen, and the 'Clapsadle carcass' of May 2009 and 'Gurney's Inn monster' of September…

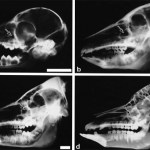

Over the past several months months and months I've been trying to complete a series of articles on the various sac- and pocket-like head and neck structures that have evolved in such diverse mammals as apes, horses, camels and baleen whales (links to the previous articles in the series are provided below). In an effort to get the series finished, here's the next part of the series. This time, we focus on rodents, rabbits and hyraxes. Yeah, just like it says above, in the title.

It's well known that pneumatisation of the skull bones is widespread in mammals: sinuses in the nasal region,…

Fossils demonstrate beyond any doubt that Mesozoic dinosaurs laid eggs, as of course do all dinosaurs today. But back during the 1960s, 70s and 80s - back when Robert Bakker and his idea about dinosaur biology were regularly featured in magazines and other popular sources - the scientific community was (sarcasm alert) delighted and enthralled by Bakker's proposal of sauropod viviparity.

Yes, mostly forgotten today is the idea that sauropod mothers were once suggested to give birth to a single, live, proportionally large baby, and to then engage in protracted parental care.

While Bakker is…

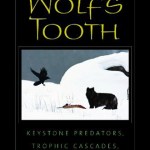

The interconnectedness of ecosystems and their components is, today, a familiar concept. Top predators eat herbivores, herbivores eat plants, and top predators keep so-called meso-predators in check too. But perhaps it isn't appreciated enough just how interconnected things can be. Cristina Eisenberg's excellent 2010 book The Wolf's Tooth: Keystone Predators, Trophic Cascades and Biodiversity draws on decades of ecological research to paint a complex picture of ecosystem interactions and cascades, of the crucial role of top predators, and of human impact on communities in the natural world.…

In January 2011, Junchang Lü, David Unwin, Charles Deeming and colleagues published their Science paper on the amazing discovery of an egg-adult association in the Jurassic pterosaur Darwinopterus (Lü et al. 2011) [the specimen is shown here: image courtesy of Junchang Lü, Institute of Geology, Beijing, used with permission]. Darwinopterus is the incredible 'transitional pterosaur', first unveiled to the world in October 2009 and rapidly becoming one of the most important pterosaurs of all in terms of what we're learning from it.

As I discussed in a Tet Zoo article published in February…

If you're a regular reader you'll have seen the recent article on those African 'great bubalus' depictions and on how they might (or might not) be representations of the large, long-horned bovin bovid Syncerus antiquus. As discussed in that article, S. antiquus - long thought to be a species of Pelorovis - is now regarded as a very close relative of S. caffer, the living Cape buffalo. As usual though, there are quite a few additional things that I wanted to cover, so here's an attempt to tie up various loose ends [the illustrations above show radically different reconstructions of…

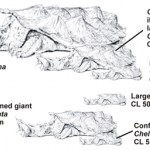

The Matamata is an incredible animal. A morphologically bizarre, highly cryptic, aquatic South American turtle, it's equipped with a super-specialised wide, flattened skull and a host of peculiar features that allow it to engulf fish and other prey in deft acts of rapid suction.

Surprisingly large (up to 1 m long), it has a very long, thick neck, and a proboscis that it uses as a snorkel. But of course you already know all of this because I covered it in depth in a series of articles published here during 2010 (if you need a refresher, see the links given below). My aim in this fifth and…

While chasing up sivathere stuff, I got distracted. Sorry.

Among the most spectacular of extinct bovids is the Plio-Pleistocene African form Pelorovis, famous for its gigantic curved horns. These can span 3 m in fossil skulls, and were certainly even longer in the living animal. Pelorovis was built rather like a gigantic, long-horned version of the living Cape buffalo Syncerus caffer, but differed from it in horn shape, in lacking the massive boss that Syncerus exhibits on its virtually conjoined horn bases, and in having a longer, lower, more antelope-like face.

The type species for the…

I don't do requests on Tet Zoo, but when enough people ask me about the same thing it does get into my head. Ever since the early days of ver 1 people have been asking me about late-surviving sivatheres. What, they ask, is the deal with those various pieces of rock art and that Sumerian figurine - discovered in Iraq - that apparently depict Sivatherium? As most of you will know, Sivatherium was a large, short-necked giraffid, originally described for S. giganteus from the Siwalik Hills of India [shown below in a well-known and oft-used illustration by Michael R. Long*] but later discovered…

Over the course of the previous 19 - yes, 19 - articles we've looked at the full diversity of vesper bat species (see links below if there are any parts you've missed). If you've been following the series on an article-by-article basis, you'll hopefully now have a reasonable handle on the morphological, behavioural and ecological variation present within this enormous, fascinating group, and will also have some idea of how the many different kinds of vesper bats might be related to one another. We've seen how bent-winged bats, wing-gland bats, tube-nosed bats, woolly bats and mouse-eared (or…

I find myself astonished by the fact that I've done it. With the publication of this article I've succeeded in providing a semi/non-technical overview of all the vesper bats of the world... or, of all the major lineages, anyway. Obviously, it hasn't been possible to even mention all 400-odd vesper bat species, let alone all the 'species groups' suggested for the more speciose genera, but I think I've succeeded in discussing all extant genera, and at least some of the fossil ones too.

As you'll know if you've been following the series, we've moved along the cladogram and now find ourselves…

Among the best known, most widespread and most familiar of vesper bats are the pipistrelles. All bats conventionally regarded as pipistrelles are small (ranging from 3-20 g and 35-62 mm in head-body length), typically with proportionally short, broad-based ears and a jerky, rather erratic flying style.

Compared to the majority of vesper bat species, the better known pipistrelle species (the common European species Pipistrellus pipistrellus and P. pygmaeus) are well known and well studied in terms of ecology and behaviour [composite above shows Common pipistrelle in various poses, with…

Here we are, so close to the very end. I am pleased and surprised to find that we're now looking at the vesper bats within Vespertilionini - the clade that (in the topology I'm using here: that of Roehrs et al. (2010)) includes the pipistrelles and noctules and their closest relatives. We'll get to those extremely familiar bats soon. As usual, they have a bunch of far less familiar close relatives... or alleged close relatives, or possible close relatives... and it's those bats that we'll be looking at here. After, that is, that we deal with lobed bats and butterfly bats. They aren't members…

By now (if, that is, you've been following this thrilling, roller-coaster ride of a series) we've gotten through the better part of vesper bat phylogeny: we've climbed 'up' the vesper bat cladogram and are now within the youngest major section of the group. Recent phylogenetic studies have recognised a serotine clade (Eptesicini or Nycticeiini), a hypsugine clade (including Savi's bat and a load of relatives), and a clade that includes pipistrelles and noctules (Vespertilionini).

Seemingly fitting somewhere within these three clades - or, perhaps, close to them - are a list of oddballs…