By Dr. Cynthia Phillips

Planetary geologist at the Carl Sagan Center for the Study of Life in the Universe, SETI Institute

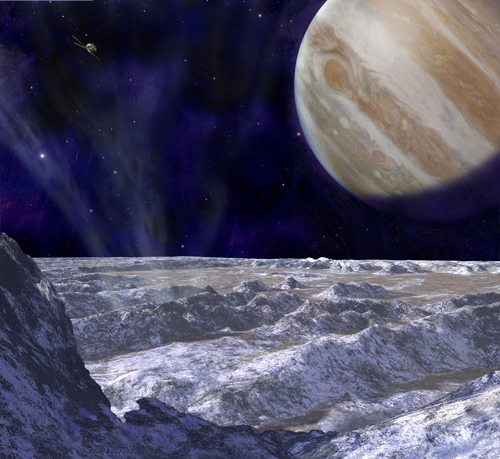

Jupiter's moon Europa could be the best place beyond the Earth to search for life. This small moon, about the size of Earth's Moon, is one of the Galilean moons first discovered 400 years ago by Galileo. The Galilean moons were the first objects observed to orbit another planet, and they revolutionized the way our solar system was understood.

Today, the moons of Jupiter are known to be a scientifically rich part of our solar system, and they are yielding a new revolution in our view of the possibilities for extraterrestrial life. Europa, in particular, may hold the key to understanding the potential for life in our solar system and beyond. Scientists believe that habitability, or the ability of life to survive on a particular world, requires liquid water, the correct chemical elements, and a sufficient source of energy. Beyond the Earth, Mars and Europa are the best places to search for life in our solar system, and Europa is unique because it is believed to have a large ocean of liquid water fairly close to the surface today, underneath its icy crust.

The Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003, made observations of Europa and the other Galilean moons, and then it was intentionally crashed into Jupiter to avoid any potential contamination of Europa. Galileo observations revealed a smooth, bright icy surface, criss-crossed by an intricate web of fractures and ridges. Scientific analyses of data from its instruments confirmed the probable existence of a layer of water about 50 miles thick beneath the ice. This means that Europa could have more water than in all of the Earth's oceans combined!

NASA is currently planning the Europa Jupiter System Mission (EJSM) to follow up on these discoveries. EJSM is an international project, and includes a NASA-built Europa orbiter and a Ganymede orbiter to be built by the European Space Agency. Both spacecraft would study the entire Jupiter system, as well as their targeted moons. Development of such a mission requires a very long lead time, however - even if design and construction of the spacecraft started now, the first Europa data wouldn't be received until 2024!

Exploration of the outer solar system helps us understand not only the habitability of our own solar system, but also the potential for life in other solar systems. Many of the "exoplanets" that have been recently discovered orbiting other stars are giant planets, much more similar in size to Jupiter than to the Earth. While it is unlikely that such giant planets would be habitable, it is quite possible that these other Jupiters have moons orbiting them just like the Galilean moons. If Europa is an inhabited world in our own solar system, this increases the chance that similar moons could be abodes for life in distant solar systems throughout the universe.

The Europa Jupiter System Mission concept is a mature one, and much work has been done over the past decade to mitigate the radiation challenges that come with operating a Europa spacecraft deep inside the radiation belts of Jupiter's strong magnetic field. A mission to Europa has consistently emerged as the top outer solar system flagship-class mission in studies by NASA and the US planetary science community. It is time to commit funding and resources to making this vision a reality.

To learn more about Galileo's 400 years of discovery, the relevance of outer solar system exploration, and the plans for EJSM, visit a special exhibit in Washington DC at the Rayburn House Office Building on Thursday, July 15th. This exhibit is open to the public.

Thanks for the comments! Actually, while the Europa mission has been in the works for some time, it's not a "done deal" yet - we're hoping for dedicated funding in the next NASA budget. So this article is meant as a reminder that we still have work to do to get the next mission to Europa funded, designed, and built. Titan is a pretty fascinating world as well, and some scientists certainly think that it's a great place to look for life - in fact, Titan and Europa were the two top candidates for the next outer solar system mission.

For Europa, we know that there is very likely a large subsurface ocean that is stable throughout the age of the solar system. Depending on the model of how the internal tidal heating works from its resonance with Io and Ganymede, there could be significant subsurface heating at either the bottom of the ice layer or the bottom of the ocean layer - making hydrothermal vent activity a good possibility. The similarity to a type of environment that we suspect was key in the origin of life on Earth is just one of many reasons that astrobiologists are so excited about Europa. My opinion is that the Europa science is well-developed and ready for the next mission. Titan is interesting, and we're still learning many new things from Cassini - but we don't really even know the right questions to ask with a future mission. So I think Titan should be next, after Europa.

Im sorry, and maybe it is intentional, but this reads like a political pamphlet: "It is time to commit funding and resources". AFAIU funding and resources have been committed for that specific purpose a long time now.

Well, habitability is not all what it is claimed to be. :-D

Currently AFAIU the most interesting body is Titan. As opposed to Mars it has the most observed thermodynamical imbalances next to Earth: surface lack of hydrogen, ethane, acetylene and a carbon isotope ratio imbalance compared to the nebula (I think). Given that one or two of those imbalances are iffy (ethane in particular, considering the seas and their ability to soak it up), it is still currently "the best place"; Mars has one imbalance (methane), Europa no known.

As for water based cellular life habitability, I like Mendez model as it fits Earth well. Given sufficient elements and energy, the bottleneck factors are water and temperature. AFAIU that puts Enceladus as the best solar system estate. As it is now believed to have large amounts of water close to the surface it is "more unique" than Europa.

Thanks for the comments! Actually, while the Europa mission has been in the works for some time, it's not a "done deal" yet - we're hoping for dedicated funding in the next NASA budget. So this article is meant as a reminder that we still have work to do to get the next mission to Europa funded, designed, and built.

Titan is a pretty fascinating world as well, and some scientists certainly think that it's a great place to look for life - in fact, Titan and Europa were the two top candidates for the next outer solar system mission.

Enceladus was also considered, but it's such a small world that even if models converge on a way to have stable liquid water reservoirs as a source region for the geysers, the amount of water is likely to be relatively small, and more importantly, the configuration is unlikely to be stable throughout geologic time. It's likely that the current conditions on Enceladus are a special kind of scenario that may last for thousands or millions of years but doesn't provide a long-term stable environment to allow life to form and flourish.

Titan is a harder case to consider. There probably is interesting chemistry going on at the surface / atmosphere interface, but, like sand blowing around on Mars, that doesn't say much about any actual internal geologic activity. So far we have yet to see any convincing evidence of cryovolcanism or any sort of internally-generated changes on Titan's surface. It's true that looking for chemical disequilibria is a good way to start looking for life, but (as is the case for the Mars methane and even for some weird Venus cloud chemistry), you have to rule out all other possible processes before considering an extraordinary claim like life.

For Europa, we know that there is very likely a large subsurface ocean that is stable throughout the age of the solar system. Depending on the model of how the internal tidal heating works from its resonance with Io and Ganymede, there could be significant subsurface heating at either the bottom of the ice layer or the bottom of the ocean layer - making hydrothermal vent activity a good possibility. The similarity to a type of environment that we suspect was key in the origin of life on Earth is just one of many reasons that astrobiologists are so excited about Europa.

My opinion is that the Europa science is well-developed and ready for the next mission. Titan is interesting, and we're still learning many new things from Cassini - but we don't really even know the right questions to ask with a future mission. So I think Titan should be next, after Europa.

Dramatic landscapes sell space exploration! In the fifties and sixties, the illustrations by Chesley Bonestell -dramatic paks and chasms- became the icons of expected future space exploration.

Unfortunately, the Moon -and the parts of Mars that were visible from the Viking landers- turned out rather flat and boring. The sudden collapse of public interest for the US space program during the seventies was due in no small part by a sense of disappointment. Where was the drama in making footprints in dust?

Titan, with its dynamic landscape of lakes, and possibly, streams, comes closest to a place that might give the Bonestell images a run for the money in terms of visual impact.

Also, the recently discovered sinkholes in the roofs of lava tube caves -lunar and martian- practically cries out for photos of astronauts climbing ladders.

I am not saying space policy should be ruled by PR considerations, but ultimately, the space program depends on the willingness of the public to provide tax money for it. A sample of ALH84001 is exciting for exobiology specialists, but 99% of the public just see another stone.

It's a good point that dramatic vistas from landers on other worlds are really what grab the attention of the general public. We've landed on Venus (but not for a long time!), Mars, the Moon, and Titan so far. And one could argue that the real impetus for the New Horizons mission, currently on its way to Pluto, was a series of stamps that the US Postal service issued with pictures of each of the planets (back when Pluto was included!) - but Pluto's picture said "not yet explored".

While there isn't a lander in the Europa mission as currently proposed, it's possible that there might be room for a small lander if funding is available. And I agree that while scientifically, it's hard to justify a Europa lander (though it'd be great to do a real chemical analysis of the surface material), the real justification for a lander is to take those essential surface pictures.

And, since the public is funding NASA, you could definitely argue that PR considerations should perhaps play a role in designing future space missions - and that could perhaps lead to the inclusion of a Europa lander to give that human perspective.

Titan, with its thick atmosphere, is much easier to land on than Europa, and gives options for future missions with boats or balloons - once the technology catches up with our imagination!

A bit off-topic; Are any of you familiar with the various novels and stories the late Stanislaw Lem wrote on the SETI issue?

"His Master's Voice" is a quite original novel about the trials and tribulations of trying to decode a message from the stars. And "Solaris" (poorly translated to English) and the appropriately named "Fiasco" are written around the near impossibility of breaking out of our anthropocentric mold when trying to communicate with The Other.