“I have difficulty to believe it, because nothing in Italy arrives ahead of time.”

–Sergio Bertolucci, research director at CERN, on faster-than-light neutrinos

A little over five years ago, the OPERA collaboration announced an astounding result: that neutrinos sent through more than 700km of rock arrived at their destination 60.7 nanoseconds faster than they ought to. That was particularly disturbing, because the speed they ought to have arrived at was the speed of light, which nothing can move faster than. Either something very, very funny was going on with the experiment, or they had just broken the laws of physics.

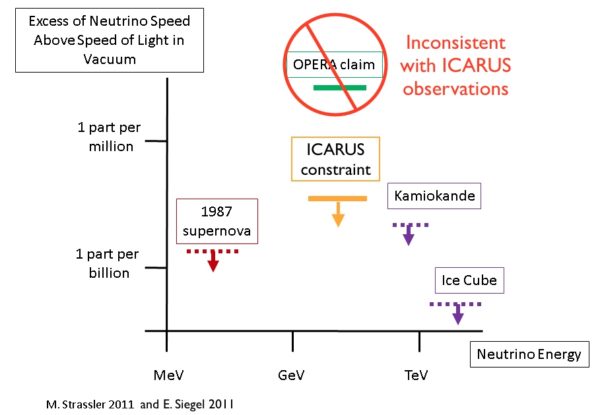

The various constraints on departures of neutrino speed from the speed of light from various experiments. All experiments display upper limits, except for OPERA's spurious positive detection. Image credit: M. Strassler (2011), modified by E. Siegel to include ICARUS and refute the initial OPERA claim.

The various constraints on departures of neutrino speed from the speed of light from various experiments. All experiments display upper limits, except for OPERA's spurious positive detection. Image credit: M. Strassler (2011), modified by E. Siegel to include ICARUS and refute the initial OPERA claim.

OPERA, quite famously, turned out to be wrong. The culprit turned out to be nothing more than a loose cable. A lot of people jumped on OPERA for publishing and publicizing a false result, but that completely misstates and misinterprets how science works, and ought to work. Rather than forcing your experimental results to agree with the previously established results, it's vital to publish exactly what you find!

One way: killfile posts on science blogs becasue you don't like the presentation

:-P

"A lot of people jumped on OPERA for publishing and publicizing a false result, but that completely misstates and misinterprets how science works, and ought to work. "

Come on, Ethan, YOU were doing that with the team. *I* was the one saying "Hey, it could be right, and that they grabbed headlines with an early 'astonishing claim' doesn't make them bad".

If you want to get picky, you weren't "jumping on them", you were just angry that they hadn't checked themselves before printing the story. But that's still telling them to STFU first, check second, print last.

How is it the OPERA team could detect the neutrinos when particle accelerators can't? As I remember from previous discussion, they get size and vector data from other subatomic particles spraying out from collisions and from that deduce what neutrinos were generated but the neutrinos themselves are never detected. Why was OPERA able to detect them and why don't they put the OPERA sensors on particle accelerators?

Because they used detectors, not particle accelerators.

A microphone and loudspeaker uses the same coils, but one is much better at its job than the other.

@ Denier

http://operaweb.lngs.infn.it/spip.php?rubrique39

there you can find more about the detector.

@Wow and Ethan,

I certainly can understand the sentiment of Ethan's article. We should never just ignore an unexpected result, and not publishing because the result may turn out to be false is no way to advance science. However, a balance needs to be struck. It is certainly incumbent on the reporters to do all possible checks to determine whether or not the result they are reporting is accurate. In the OPERA case, I don't really have the personal knowledge to determine if that loose cable was something they should have found prior to publishing or not, but in general, IMO, an unexpected result should not be ignored or discarded, but it should also be subject to intense scrutiny prior to publication to determine if some error is the cause.

No, sean "not publishing because the result may turn out to be false " is NOT what is being proposed.

Are you aware of the truth in advertising laws?

Something like that for both news outlets and science journals, so that instead of just ignoring everything said by "experts" because "they're all liars", you can ACTUALLY TRUST WHAT THEY SAY IS FACT CHECKED.

You know, like how it worked for hundreds of years in science and decades for news.

And you know what? Science progressed despite this refusal to print any old crap, and news wasn't imposing a nazi state on the entire country.

" It is certainly incumbent on the reporters to do all possible checks to determine whether or not the result they are reporting is accurate. In the OPERA case,"

Such checking being things like

a) are they legitimate scientists?

b) is the experimental setup considered valid by the scientific community?

c) is the result calculated appropriately

d) is the conclusion derivable from the results

These were all things that newspapers used to do because they had investigators checking up on the facts. Even if they didn't have special expertise (and many big papers did have science correspondents that knew science enough to weed through the stinkers), they checked up with the appropriate sources.

What they didn't do was print "These scientists said X", or, to be "in depth", print "These scientists said X, this person said it was Y instead".

I think in the OPERA case the research team gave it what they considered to be intense scrutiny, and finally published because they couldn't find an error - even though they recognized that the result was probably an error.

In fact, IIRC, this was the group that basically put out an editorial comment with their publication saying (in paraphrase), 'okay everyone, please find our mistake.'

Obviously if every grad student in the scientific world was asking readers to find their mistakes, that would be a problem that would break the system. But when we're talking about a 'big science' experiment that cost millions of dollars to run and likely won't be replicated independently for years - if at all - I have no problem with the research team publishing a result they suspect is in error but can't figure out why. Let's get our money's worth out of that baby; publish your problematic data and let's see what we can find. Heck, for multi-million dollar hard to repeat experiments let's publish even the negative results and let people chew on it to see what they can find.

In fact, there is much more than a loose cable in the story of the superluminal neutrino.

I recommend the novel “60.7 nanoseconds: an infinitesimal instant in the life of a man “ (easily find on the Internet).

"Written with an insider’s sense of authenticity and atmosphere, the story of the particles supposedly breaking light-speed becomes a cautionary tale of the traps and dangers lurking on the path to new scientific discoveries."

My bad. My comment was unclear. By "reporters", I actually meant those reporting the result, not reporters in the sense of journalists. That throws another wrinkle into things though. As eric said, the OPERA collaboration essentially realized that their data was likely wrong and reported the results so that others could try to find the mistake. It is the journalists who wrote all the "Einstein was wrong"-type headlines and blew the whole thing out of proportion.

I'd like to pick up on the data for the gravitational constant, G. The fact that we keep getting different results could be due to the fact that G is variable. This a priori assumption that it's a constant may be wrong.

The earth's mass is assumed to act as a point at the centre of the earth. Is that the geometric centre (centre of the sphere)? or is it the centre of gravity? The centre of gravity would depend on the densities of local areas e.g. the densities of mountainous regions would be greater than those of flat plains which would be greater than those of an expanse of water.

So the centre of gravity/mass would be closer to the denser parts of the earth. The different values for G could be due to the local densities of the regions in which the experiments were done. I forecast that an experiment done in the middle of the pacific would give a lower reading for G than has hitherto been recorded.

This is important because, if G is variable, then it could affect the perihelion shift of Mercury which is almost a solid lump of iron with a liquid core. G should be measured on Mercury (despite the harsh conditions) and on a gas giant just to get a flavour of the value of G.

In the worst case scenario, it would show that G is fairly similar to that found on earth. I say worst case because it would show G to be a constant within experimental error. But it would be a confidence boost.

The surefire way for some people to never find anything new in science is to confuse "new" with "correct".

Go look at any A-level or high school textbook and they will teach you what the centre of gravity is, starting fromthe very simplest "two masses on a beam".

When you've learned what maths says, then you need to work on what science is.

This will take you a very long time, kasim. A VERY long time indeed.

SL, you didn't want scientists to be placed where you think coalminers should be.

Why?

1) coalminers work physically hard. BUT

- machinery does most of the hard work.

- you're elevating "manly" physical effort as the marker for "worthy"

- You don't need to work 7 years or more to become a coalminer

- We pay them as much as someone senior in ecology. Don't get me started about the pay of postgrads working for them...

2) They risk their lives. BUT

- New York taxi drivers risk their lives more than any other group. You're not putting them ahead of police, never mind the coal miner. And they don't sweat at their labour. Pfeh! What are THEY worth, eh?

- Who says scientists aren't risking their lives:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-tayside-central-37774048

If you think it's all steak and gravy for scientists, that they all sit safe behind a desk, go and join up to help a geology group at university, or an ecological expedition.

Hell, watch the behind-the-scenes footage of David Attenborough's series on life on earth. Look at the lives of people who go to Africa to study Elephants. Australia to study sharks.

Your ignorance (unwitting, I bet, since I suspect you KNEW that the above was true) is because you don't think scientists are worthy of respect,you look down on their efforts, don't consider what they ACTUALLY HAVE TO DO when they're not sitting in a lecture theatre and teaching the next set of scientists to be told they're worth less than a coal miner by someone who has never had to run a field expedition for 9 months, with all of that time having to negotiate the necessary funds to extend to another 9 months next year (and for the next five, any of which might get its funding chucked out).

Try it sometime.

In short, SL, you have the stereotype and paintall scientists with that single image.

It;s no different than any other bigotry, racism or sexism.

You find a comforting archetype then instead of thinking, you plonk that stereotype in wherever you need to think about the topic.

It's when you do that KNOWINGLY that it becomes a bad thing, but it's still not good if you do it UNknowingly; and it's still worth being corrected on. The action is the same, even if the mens rea is different.

@ Wow

I think you posted this on a wrong thread... But non the less. I think you are misunderstanding what I was trying to argue.

It's not about coal miners per say. I gave them as an example of a type of jobs which are hard and dangerous but that are usually overlooked or treated as being menial in grand scheme of things.

My argument is why should ALL scientists be a priori treated with tremendous respect? What is it about their job that's more special then other professions? I don't think they should be treated any differently then anyone else. Miners were given just as an example.. maybe a bad one.. but they were not the point of the comment.

@ Wow

"...you don’t think scientists are worthy of respect,..."

No. I am asking why does OP think they are worthy of MORE respect then everyone else in their professions. Read my original comment.

I have exact SAME professional respect for Michelangelo as well as for Einstein. Or to bring it down a notch.. exact same respect for my doctor as well as for my accountant. They all do things which I don't do, and we are all significant or insignificant in the big foodchain.

I find it incredible that you would accuse me having archetypes or stereotypes when I am the one arguing that noone should have special treatment. LOL!

"I think you posted this on a wrong thread… "

Aye, posted it over there.

Putting this on the correct thread, follow it there.

Kasim @12:

This is news to me. Are there specific experiments you're citing? If so, what are they?

The different figures for G are in the article itself.

Sorry. They appear in the article on forbes.com: http://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2017/01/04/the-surefire-way….

"The different figures for G are in the article itself."

No they aren't. If they were, then this was a lie:

"The fact that we keep getting different results could be due to the fact that G is variable. "

So, either you're lying in one place or lying in the other.

Of course you could be lying both times.

@21: Ethan makes two reasonable points explaining the difference. First, 15 years' improvement in experimental techniques between measurement. Second, confirmation bias. Had the value been changing over that time, we would've seen a progressive change in the value, but we didn't.

Second, while Ethan does call it 'way off', this is probably from the perspective of a cosmologist. As an outsider, I don't particularly see 6.674+/-0.001 E-11 as being "way off" from a set of values centered around about 6.6725 E-11. The difference is larger than the error bar, sure, not so big as to make me immediately leap to the conclusion that our fundamental understanding of gravity must be wrong.

Third, we can do a quick back-of-the-envelope test of your hypothesis and see what it would predict. The measurement difference translates into about a 0.0015% change per year. That would mean gravitationally bound objects 1,000,000 light years away should behave as if G was 1500x smaller than it is today. We (obviously) don't see that. So to first approximation, your hypothesis must be wrong. You'd have to hypothesize some complex non-linear change in G to explain the measurement but still be consistent with everything else we see. That seems...unlikely.

Having said all that, I have no problem whatsoever with cosmologists performing additional measurements of G. If they do and it turns out that the results fit a pattern of a slowly increasing G, so be it. The point I take issue with is claiming the current data supports that hypothesis. I don't think it does. Could additional data lead us to that conclusion? Yes sure. But IMO, this data doesn't.

Kasim,

In the medical field, they have a saying: "If you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras." In science, this sentiment is captured by Occam's Razor, namely that if two explanations equally well explain the observation, go with the simpler one.

Is it possible that a change in G has caused the (slightly) differing measurements of its value? Sure, but it is also possible that, just as Ethan points out, changes in the way we measure that value have resulted in a better measurement demonstrating that we measured the value of G incorrectly in previous experiments. That's the simpler explanation. Until there's evidence that this explanation cannot account for, that will be the accepted explanation.

It is incumbent on you (or anyone else supporting your idea) to come up with evidence to convince the scientific community that you're right. It is not up to the scientific community to demonstrate that you're wrong.

And changing the value of G at Mercury would accomplish this how? Remember, this silly assertion implies that you have to preserve Kepler's third law while you're at it.

#24. That's a measured response and I appreciate it. The small theorist has an uphill struggle against a well-resourced, well-funded mainstream scientific community; although some scientists may disagree about being well-funded.

Ethan himself, in another post, warned about coming up with a theory and then finding evidence to support it. This seems to imply find the evidence first before publishing a theory. But, isn't that what OPERA did? I acknowledge that OPERA were conducting a practical experiment and they published its results.

Back to the drawing board for me.

WAG isn't theory, kasim. And your "poor little me" routine isn't fooling anyone.

The crackpot has an uphill struggle against people who can tell Bullshit from Reality.

And isn't your entire spielhere about having a theory (G changes) and then looking for evidence to support it (Mercury's perihelion)? Kinda killing your own "theory" here, aren't ya?

But, hey, when you get an experiment designed to show G changes, print the results up and set it for peer review. We'd be interested in THAT.

In the article: http://www.forbes.com/forbes/welcome/?toURL=http://www.forbes.com/sites…, Ethan published a list of different values of G. I didn't analyse them in any way; it just struck me that G maybe variable.

We'll do well to measure G on another planet to give us more confidence in the value of G. I hear that Elon Musk is preparing a Mars Expedition. Maybe then such an experiment can be made just as astronaut David Scott did the hammer and feather experiment on the moon to prove that Galileo was right.

Theoretical physicists publish theories without any proof and experimental scientists prove them. Einstein was a nobody before his miracle year in 1905. If he began his career today, he'd still be a nobody with the way people are treated. I know what you're thinking: "I'm no Einstein" said Einstein.

IIRC, Ethan warned about coming up with a theory and then only looking for evidence to support it. That's bad.

Coming up with a theory and then asking what it would post-dict is just fine. In fact, you *should* do that. But when you do that, you should be looking at the things we know that are problematic for your theory too, not just the bits of past knowledge that would support it.

A good example is my back of the envelope calculation in @23. A detectably increasing gravity over 15 years implies it was detectably weaker deeper in the past. Well, we can look very deep into the past, via telescope. The hypothesis of changing gravity doesn't appear to be consistent with the evidence we have already collected. This is important to consider. If you only look at the data points on Ethan's graph, you are not doing due diligence as a theory-developer; you must also consider this data which would be problematic for your idea.

Theory development is not really an issue of 'do I start out just doing post-diction or just pre-diction?' You do both. You make predictions to be tested, and you look at evidence that confirms it, and you look especially hard for evidence that may disconfirm it. We look extra hard for the stuff that may disconfirm it because, as Feynman said, "the first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool." When you look only at the data that confirms your idea and discount or ignore data that doesn't fit your theory, you are fooling yourself.

"Ethan published a list of different values of G. I didn’t analyse them in any way; "

Then you should have kept your mouth shut and your keyboard unused.

Get an opinion before spouting one out.