tags: oceanography, plastic bathtub toys, duckies

Have you seen one of these duckies? (May be bleached white by now).

If so, please report your find to researcher, Curtis Ebbesmeyer.

Image: Simon de Bruxelles.

If you live in Great Britain, you could earn a £50 (US$100) reward if you find a plastic duck on the seashore during your upcoming holidays.

It turns out that a flotilla of thousands of yellow ducks, green frogs, blue turtles and red beavers (all of which are bleached white by now), each branded with the logo "The First Years", are headed your way after bobbing around the Pacific, Arctic and finally, the Atlantic oceans nonstop for the past 15 years. After wandering for approximately 21,800 miles, the plastic toys are expected to make landfall on the beaches in Britain very soon.

The plastic toys (I like referring to them collectively as "ducks") began life in a Chinese factory and were being shipped to Tacoma, Washington, USA from Hong Kong when several 40-foot containers, one of which was filled with 29,000 ducks, fell into the Pacific during a freak storm on January 29, 1992.

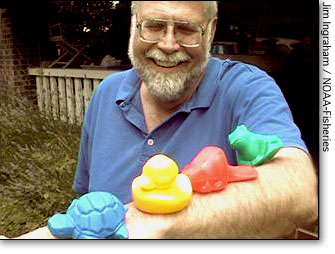

"Twenty-nine thousand objects that all came from the same place -- what an incredible opportunity!" Gloated Seattle-based oceanographer, Curtis Ebbesmeyer (pictured). Ebbesmeyer is the world's expert on the yellow duckies.

Most of the ducks floated south through the tropics, washing ashore months later in South America, Australia and then in Indonesia. But a flock of 10,000 ducks were captured by the Subpolar Gyre and instead headed north. By the end of the year, some were washing up on Alaskan shorelines while the remainder of them were moving eastwards again.

"The ducks went around the North Pacific in three years -- all the way from the spill site to Alaska, over to Japan and back to North America," said Ebbesmeyer. "This was twice as fast as the water at the surface -- so I began to call them hyper-ducks."

After that, the ducks continued to move north to the Arctic Ocean, where they became frozen into the Arctic pack ice. Winds and currents pushed the ice eastward on a 2,000-mile journey over the North Pole before turning south, and moving past Greenland and Iceland. Those plastic ducks that were not squashed or otherwise permanently damaged were then freed when the ice melted, and they wandered into the open waters of the North Atlantic. The first Altantic landfall occurred in 2003, when a duck washed up in Maine and a frog was discovered in Scotland.

Oceanographers predict more ducks will wash up on the shores of southwest England, Ireland and western Scotland in the summer of 2007.

Between 2,000 and 10,000 containers are lost from ocean-going vessels every year. They are filled with everything from Nike sneakers (80,000 were lost into the Pacific in 1990) to Lego building bricks (five million fell into the North Atlantic in 1997).

Unfortunately, this constant infusion of refuse is filling up the oceans with tons of garbage and is killing millions of sea animals every year. This floating junk has transformed the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, a gigantic rotating current that is thousands of miles across, into a trash-filled region is commonly known as the Garbage Patch. One researcher who sailed through the Garbage Patch in 1998 described it as a giant toilet, forever swirling but unable to flush.

"I was confronted, as far as the eye could see, with the sight of plastic," he wrote, no doubt, in dismay.

The ratio of plastic to plankton in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre is approximately six to one, which is harming marine life from the very beginning of the food chain, according to a 1999 paper published by Ebbesmeyer and a colleague, marine scientist Charles Moore.

To trace the movement of the plastic ducks, Ebbesmeyer collaborates with Jim Ingraham of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Ingraham developed the Ocean Surface Currents Simulator (OSCURS), which follows the surface currents of the North Pacific. OSCURS studies the effects of currents on fish eggs, larvae, and plankton and on the behavior of migrating salmon and marine mammals. But OSCURS is also providing details for how plastic flotsam moves around the oceans based on landfall data.

Sources

Curt Ebbesmeyer profile (lots of information and image, site includes free PDFs and video)

Times (quotes, top image)

Daily Mail (quotes)

This is one of my favourite science stories ever, since I heard about it on NPR a couple of years ago. Tracking rubber duckies around the world, recording every sighting and beaching, and building a model of oceanic water movement using those data! Brilliant!

Do they still quack?

I'll meander down to the beach on my next R&R, never know one might wash up on the beach at Largs.

I've heard this and the Nike shoes stories before, but the "Garbage Patch" is new to me, as is the 6-to-1 plastic-to-plankton ratio. Six to one? Six units of plastic to one unit of plankton? (What are the respective units here?)

That's appalling! No, it's worse than that; it's terrifying!! What (if anything) is being done to (i) clean up the mess; and (ii) stop so many containers from going overboard (i.e, prevent the problem from getting worse)?

There are clearly economic (financial) incentives to prevent containers from going overboard (albeit there will also always be accidents), so it seems to me the shipping companies and their customers would be highly interested (and, hopefully, proactive) in preventing containers from going overboard. Are they? Or do they just take the insurance money and run? (And is the cost high enough to get the insurers interested in the problem? Somehow, a container of rubber duckies doesn't seem like a sufficient incentive; a container of, say, cars, might be, but cheap toys?)

But the cleanup--I have no idea how that could be done--strikes me as something lacking an "obvious" (that is, short-term financial) incentive, and hence, I'd guess, not much is happening. And since it is (presumably) in "international waters", there isn't much in the area of law/authority which applies, or at least which can be (and is) enforced.

Heh, planning on being in Skye for a bit this summer -- I'll keep my eye out.

I know that sea turtles are very hard hit by plastic trash. For the vast majority of their very long evolutionary history, the only things they were likely to encounter in the open ocean were things they could eat; so when they encounter floating things in the open ocean they eat them. The number that die with their bellies and bowels blocked with plastic trash is appalling.

The ducky up top and the ducky on the researcher look really different... is that the right one?

How sad, I'll never think of the Sesame Street song

" Rubber Ducky, you're the one..." In quite the same way again

An animal never fouls it's own den, ah.. but we are human

and have not yet achieved that level of behaviour.

I wrote a lengthy cover story about the journey of the toys for the January 2007 issue of Harper's Magazine ("Moby-Duck, or, The Synthetic Wilderness of Childhood," www.harpers.org/archive/2007/01/0081345). The journey makes for a good story, but as the ducks have circulated through the media for the last fifteen years, they've turned into chimeras, part fiction, part fact. The coast of New England was similarly forewarned of a duckie invasion in 2003, but the only somewhat credible sighting--the one in Maine--is doubtful at best. Neither the beachcomber in Maine nor the one in Scotland kept the evidence. If you do go duckie hunting, look for the following identifying characteristics: The toys are made from rigid not pliable plastic. Bleached by the sun, the ducks will be white or off-white, and the beavers will be off-white or beige. The turtles will still be blue, however, and the frogs still green. Only the ducks bear the First Years logo. Good luck.

Wow, thats a bizarre plastic duck obsession you've got there.

ducks, wow that is not at all randoma and weird,...sigh

Looks hot I love ducks a lot.

I would reccomend you buy a duck from a dollar store.

I wanted one pair.

Where can get one, and how much it is.

Nice