tags: researchblogging.org, evolution, social behavior, cooperative breeding, environment, global warming, climate change, African starlings, birds

Superb starling, Lamprotornis superbus, a cooperative breeding savanna dweller that is abundant throughout northeast Africa.

Image: Dustin R. Rubenstein [larger]

Postponing one's own reproductive efforts to help other individuals raise their offspring might seem like a bad choice, evolutionarily speaking. But cooperative breeding, as this behavior is known, is fairly common in the animal kingdom, although the reasons underlying the evolution of this behavior remain obscure. Recently, a new study has shed some light on reasons for the evolution of behavior by revealing that climactic uncertainty causes some species of African starlings to group together to help each other raise offspring. In most bird species, young females will leave the family in search of mates while males remain with their families.

This study was conducted by behavioral ecologist and evolutionary biologist Dustin Rubenstein, who is a Miller Fellow in the Department of Integrative Biology and the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at UC Berkeley. Rubenstein found that starling species that engage in cooperative breeding all live on the African savannah, which are semi-arid grasslands that are subjected to unpredictable rainfall patterns. Those species that do not engage in cooperative breeding were found mostly in forests, which have more reliable annual food resources.

"[R]ain equals food to the birds because it drives patterns of insect availability," observed Rubenstein, who has studied a large number of starling species in Kenya for the past decade. "[So] we think that by living in family groups with helpers that aid in feeding babies, these birds can cope better in these unpredictable savannas."

There are 117 starling species worldwide, but only those in Africa, where savannas are common, engage in cooperative breeding. Starlings that live in temperate or jungle environments in Europe, Africa and Asia, do not.

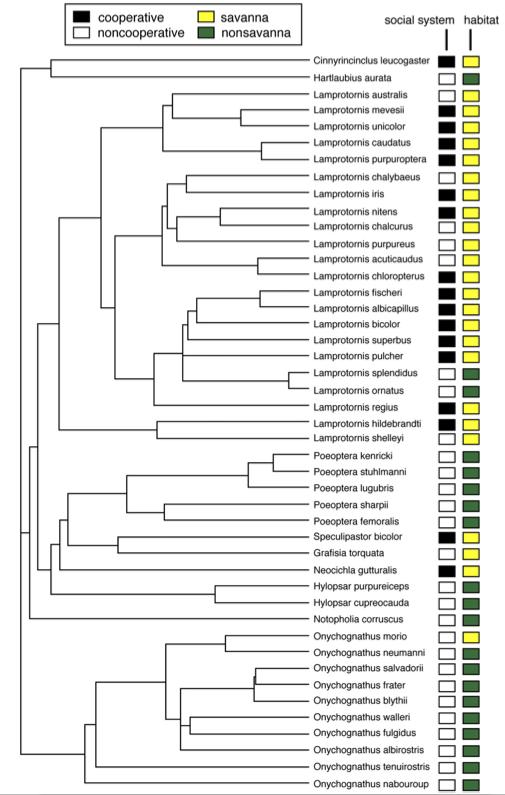

To do this research, Rubenstein and his colleague Irby J. Lovette, director of the Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York, constructed a family tree of African starlings using mitochondrial and nuclear intron DNA collected from wild birds that they captured in Africa, from birds housed in zoos and from museum specimens. They then mapped the preferred habitat type, savannah or non-savannah, and social system, cooperative or non-cooperative breeders, onto this phylogenetic tree (see Figure 1, below)

Figure 1 Molecular Phylogeny of African Starlings and Their Social Behavior in Relation to Environmental Factors.

This ultrametric Bayesian MCMC topology is based on the combined analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear intron sequences. The social and environmental characters used in comparative analyses are indicated to the right of each terminal species. All characters are discrete and were treated as binary; a key is given above the tree. Social systems were divided into cooperative (black box) and noncooperative (white box). Habitats were divided into savanna (yellow box) and nonsavanna (green box).

Based on this analysis, the researchers found that cooperative breeding behaviors evolved repeatedly and at various times as starling species moved from forests to savanna habitats. Cooperation apparently confers an evolutionary advantage, because in very dry years, when food and other resources are scarce, it helps ensure that more offspring survive.

"If we saw just a single evolutionary origin of the behavior and a single switch in habitat, it would be very weak evidence of a relationship between these factors. But we found that cooperative breeding and habitat changed repeatedly in the same direction at the same points in the tree, so we can make a much more powerful statistical argument that the factors are related," Rubenstein said.

"What's important here is how many times behavior changed," agreed Lovette. "If you find the same pattern consistently repeated, you can be confident of cause and effect. In this case, we found cooperative breeding evolved when different starling species moved from forests to savannas."

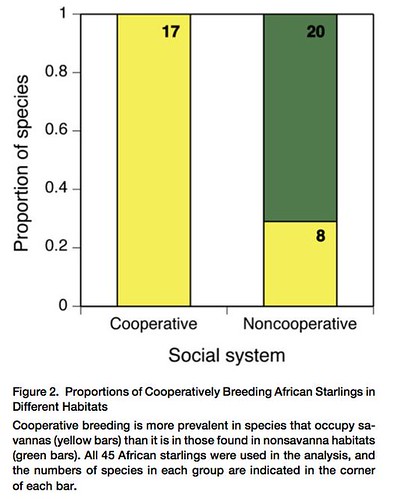

When the researchers analyzed the birds' social system and compared it to their habitat type, and they found that one-third of all starling species were cooperative breeders. Further, they found that all of the cooperative breeders live in savannahs, while most of the noncooperative breeders were found in forested habitats, which are more predictable environments (Figure 2).

Basically, when faced with an uncertain and unpredictable environment, it pays evolutionarily to live and breed in social groups that will help the birds to weather the bad times and make the most of the good times.

"Living in cooperative family groups may be like a form of insurance against the unpredictable nature of the environment, because it allows individuals to maximize their reproductive success over the course of their lifetimes," Rubenstein said.

Evolution of cooperative breeding behavior due to an unpredictable environment might also be applicable to other animals, even to humans. For example, it's possible that global warming could drive the evolution of social behavior in temperate zone animals that don't normally live in family groups because changing weather patterns are becoming more variable worldwide.

"We think this relationship between sociality and temporal variability in rainfall and, hence, food availability, might help explain the distribution of cooperative breeding in other groups of birds, and even some mammals, living in semi-arid environments around the world," Rubenstein noted.

This research appears in the August 21st issue of the journal Current Biology.

Sources

"Temporal Environmental Variability Drives the Evolution of Cooperative Breeding in Birds" by Dustin R. Rubenstein and Irby J. Lovette. Current Biology 2007 17: 1414-1419. [abstract]

Press release (quotes)

Nice post! I was goign to blog this but don't have time, so I'm glad you did it better that I could have.

At first glance, postponing one's own reproductive efforts to help unrelated individuals raise their offspring might seem like a bad choice, evolutionarily speaking.

It is.

Recently, a new study has shed some light on this behavior by revealing that climactic uncertainty causes some species of African starlings to group together to help each other raise offspring, whether they are related or not.

Really? Your quotes from the article refer only to "family groups," not unrelated individuals. E.g. "Living in cooperative family groups may be like a form of insurance against the unpredictable nature of the environment, because it allows individuals to maximize their reproductive success over the course of their lifetimes," Rubenstein said..."[So] we think that by living in family groups with helpers that aid in feeding babies, these birds can cope better in these unpredictable savannas."

you're right! i fell asleep at the switch on that one. sorry about that.

Hi!

Your submission was selected!

The Natural Sciences Carnival is up here

Thanks for your contribution for the Natural Sciences Carnival 1st edition.

Link, post, comment, spread it!

And don't forget to participate in our next edition!