tags: researchblogging.org, Seychelles warbler, Acrocephalus sechellensis, birds, evolution, social behavior, helping behavior, grandmothers

When talking about evolution, some people have wondered aloud about why grandmothers exist in human society since they clearly are no longer able to reproduce. However, these people are conveniently overlooking the fact that grandmothers perform a valuable service; they help their relatives, often their own children, raise their offspring -- offspring that are genetically related to them. But curiously, grandmother helpers have not been documented to occur in birds, where most of our research into cooperative breeding systems occurs, so this makes the question even more intriguing: Why are there no avian grandmothers? Further, since cooperatively breeding birds are relatively long-lived, grandparental care should indeed be identifiable, especially if cooperatively-breeding bird societies are observed long enough.

In a paper that was recently published online by David Richardson, an evolutionary biologist from the University of East Anglia in the UK, and his colleagues investigate this phenomenon further. They relied on 26 years of data based on observations of Seychelles warblers, Acrocephalus sechellensis (pictured, top), living on Cousin Island in the Indian Ocean (see maps, right and below). In addition to behavioral data, they marked nearly all of the birds on the island with a unique combination of colored leg bands so individuals were easily identified at a distance. They also relied on DNA fingerprinting to establish both the parentage for all of the marked birds and the degree of genetic relatedness between primary breeding birds and deposed female subordinates.

In a paper that was recently published online by David Richardson, an evolutionary biologist from the University of East Anglia in the UK, and his colleagues investigate this phenomenon further. They relied on 26 years of data based on observations of Seychelles warblers, Acrocephalus sechellensis (pictured, top), living on Cousin Island in the Indian Ocean (see maps, right and below). In addition to behavioral data, they marked nearly all of the birds on the island with a unique combination of colored leg bands so individuals were easily identified at a distance. They also relied on DNA fingerprinting to establish both the parentage for all of the marked birds and the degree of genetic relatedness between primary breeding birds and deposed female subordinates.

The Seychelles warbler is a small long-legged songbird with a narrow beak that is currently found in the lowland forests on three granite and coralline islands in the Seychelles. It is insectivorous, gleaning small insects from the underside of leaves of trees and other plants. In 1968, the Seychelles Warbler was on the brink of extinction, with only 26 birds surviving on Cousin Island. However, the bird is recovering, thanks to local conservation efforts. This plainly colored brownish passerine more than makes up for its drab plumage by producing a beautiful song.

But most interesting, these birds are cooperative breeders who generally rely on "helpers" that assist the breeding pair raise their chicks. These subordinates are usually young female offspring from previous nests produced by the resident pair.

"In the vast majority of cooperatively breeding species, helpers are offspring that have delayed dispersal and remain within their natal group," write the authors in their paper. "Consequently, helpers are normally assisting their parents and often accrue indirect fitness benefits by doing so."

But after documenting the social behaviors in Seychelles warblers for a number of years, it became apparent that some of these helpers were not subordinate females, but instead, they were formerly dominant females who were deposed from their primary breeding position.

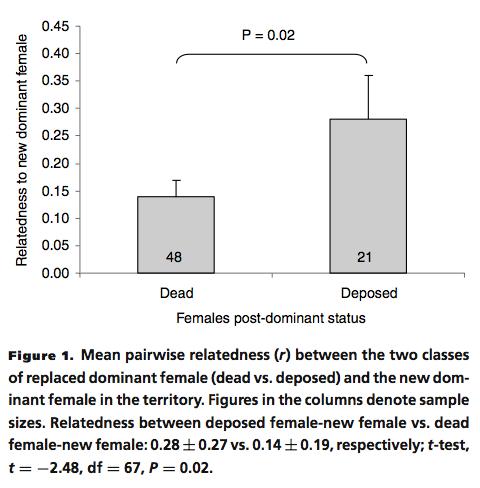

Richardson's team found that deposed dominant females were more closely related to subordinate females who were replacing them than were dominant females who died before being replaced by a subordinate female (figure one, below);

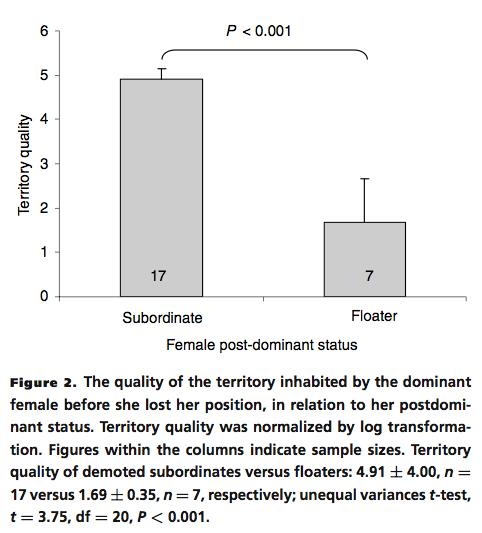

Dominant females that were deposed instead of dying could either remain on territory and act as subordinate helpers, or they could become "floaters"; birds that roamed freely from territory to territory. This decision was heavily influenced by the quality of the territory that the birds occupied. According to the team's findings, deposed females who occupied higher quality territories remained as a subordinate while those who lived on poorer quality territories became floaters (figure 2, below);

These data suggest that there was little competition for food on higher quality territories, regardless of the number of subordinate birds present. Thus, by remaining as a subordinate, a deposed female increased the reproductive success of her relatives, which also increased her own genetic contribution to future generations. On the other hand, a deposed female who became a floater did so because, by leaving a poor quality territory, she reduced competition for limited food and thus, increased her relatives' reproductive success.

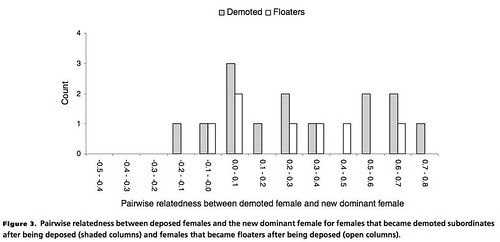

The team also found that the degree of relatedness between demoted subordinates and floater females in relation to the new dominant female tended to be greater than expected by chance alone, although they were not able to apply a statistical analysis because the sample sizes were too small (figure 3, below);

However, it is important to note that not all demoted females were highly related to the dominant females because subordinate females on a territory can and do produce a few offspring of their own and also because dominant females may sometimes come from other territories.

Interestingly, other variables, such as age of the deposed female, her previous subordinate experience (an indirect measure of her overall quality), or the presence of a new dominant male on the territory had no effect on whether a deposed female remained as a subordinate or became a floater.

This is the first time that grandparent helping has been documented in birds, although there are several other species where kin-directed helping behavior has been observed.

However, it is important to note that in other avian helping species, "all individuals attempt to breed independently each year and only move to helping if their nest fails. Consequently, this behavior would be very different to that of individuals that forgo independent breeding and become subordinate grandparent helpers."

This research was published in the journal, Evolution.

Source

"Grandparent helpers: the adaptive significance of older, postdominant helpers in the Seychelles warbler" by David S. Richardson, Terry Burke, and Jan Komdeur. Evolution (2007). [doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00222.x (abstract) or free PDF]

Non breeding Eider ducks (Somateria mollisima) that are either too old to breed (i.e. grandmothers) or too young often look after "creches" of ducklings....babysitting grandmothers if I ever heard of it.

For pics of eider (including duckling):

http://www.naturalbornbirder.com/gallery/eider.html