tags: researchblogging.org, psychology, trauma, emotions, 9-11, psychological health

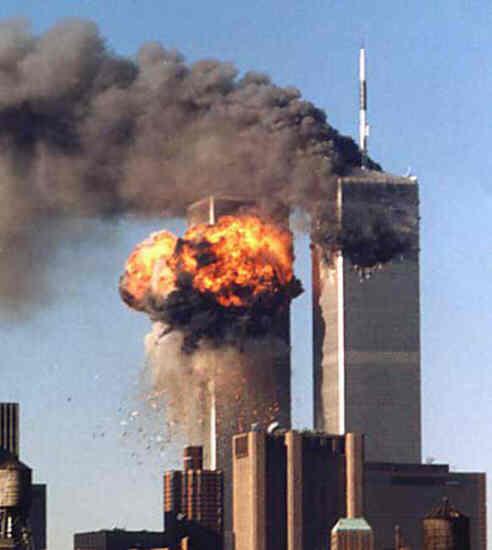

To talk or not to talk, apparently that is the question, especially after a collective catastrophe, such as 9-11 or the Virginia Tech University shootings. A paper that will be published in the June issue of Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology reveals that -- contrary to current opinion -- verbally expressing one's emotions is not necessary to cope successfully with a community tragedy, and in fact, doing so might actually be harmful.

Expressing one's emotions in the aftermath of a community tragedy is often the expected "normal way" for coming to terms with these events and one's experience with them. Worse, television psychologists often tout this, too, without any scientific evidence to support their assertions.

"This perfectly exemplifies the assumption in popular culture, and even in clinical practice, that people need to talk in order to overcome a collective trauma," observed lead author Mark Seery, an assistant professor of psychology at the University at Buffalo, NY.

The psychological community claims that supressing one's emotional reactions to a community trauma is counterproductive and likely to result in increased physical and mental problems in the future.

"It's important to remember that not everyone copes with events in the same way, and in the immediate aftermath of a collective trauma, it is perfectly healthy to not want to express one's thoughts and feelings," Seery points out.

To learn more about how expressing or supressing one's emotions affects people, the researchers used online surveys to collect data from 1,559 Americans across the nation. The surveys were an open-ended question asking about one's "thoughts on the shocking events of today" and was emailed on September 11, 2001, and continued for a few weeks afterwards.

"If the assumption about the necessity of expression is correct, then we should expect those who are failing to share would be the ones to express more negative mental and physical health conditions," reports Seery. However, their findings did not support this assumption at all.

When the team compared the long-term physical and psychological health of "expressive" people to "supressive" people, they were surprised to discover that those who chose to remain silent about their emotions reported fewer health problems two years later.

"I would have thought that the people who did not want to express, that they would have been worse off," admitted Seery.

Interestingly, the team also found that people who expressed more ended up with worse mental and physical health two years later than did those who expressed less. This surprising effect was even more pronounced among those who lived close to the twin towers.

After reading this paper, I was left wondering if those who are less likely to express their emotions after a collective trauma are also less likely to report physical or mental health problems?

But nonetheless, these findings have important implications for how people should be expected to respond to a traumatic event that affects a community or even an entire nation. Recognizing that not everyone reacts in the same way to such events, nor expecting them to, makes intuitive sense to me. In short, respecting differences in individual coping mechanisms seems to be the most healing.

Source

Seery, M.D., Silver, R.C., Holman, E.A., Ence, W.A., Chu, Q.T. (2008). Expressing thoughts and feelings following a collective trauma: Immediate responses to 9/11 predict negative outcomes in a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(3)

This just confirms my long held belief that psychology the worst of the pseudo-sciences (right behind human medicine). Practices based on everything but real data, it's nice to know that someone is trying to investigate some real scientific questions, but I can't imagine the damage that has been done when trying to "help" people.

How did they collect data on health? I'm wondering if the people who didn't talk about their feelings also didn't report any later health problems.

Curiously, the Fourth Estate has never questioned the sudden emergence years ago of 'grief counselors', who have as much training as guidance counselors.

I'm guessing they are morbid types who enjoy participating in the emotional suffering of others, especially when they can get paid for it.

I suspect that reviewing and discussing the traumatic event is meant to allow "release of the emotions", but in fact serves to stabilize and reify the memories, preventing their natural suppression.

i heard from Mark Seery today, who writes in response to some of our questions;

Therapists. Talking about it. Oy.

I'm 50-something, bipolar, and required to see a therapist as part of the program that lets me see a doctor and get my meds for free. If I didn't have to, I wouldn't. It's been going on for over 4 years, and I do my damnedest to divert the conversation and talk as little as possible about anything that's even potentially upsetting, because:

[1] Everyone, especially the pros, should have figured out by now that picking at scabs and pounding on bruises - whether physical or emotional - is not the way to heal them;

[2] The way to leave something behind is not by repeatedly coming back to it (HELLO! Ever hear of turning your back and walking?);

[3] In my case, there's not really anything to talk about. It's a medical condition, not an emotional or (Ceiling Cat forbid!) "behavioral" (DAMN, I hate that word!) problem; and

[4] I only end up confused, frustrated and even more depressed over not being able to communicate meaningfully with someone who's only seen "mental" illness from the outside. (Just try to explain the sensation of feeling just plain bizarre, or the weird, disconnected "flat" feeling you can get from some meds. Trust me, it can't be done.)

I get a whole lot more real "therapy" out of just hanging out with my best buddy, a fellow beeper a couple of years older than me who's also had the experience of crashing and burning when you're heading into middle age.

You might think we'd have trouble communicating because he's predominantly manic and I'm about 90% depressed, but we're constantly amazed that we've used almost identical metaphors all our lives (for instance, the giant vacuum hose sucking your soul out) to describe what's going on. We don't have to dig into painful stuff or try to explain ourselves the way we have to do with outsiders.

Maybe "grief counselors" and therapists in general do help some people. I've known quite a few people who say they've benefitted from therapy. But for me and my friend - and for a lot of other people, I'm sure - the "pros" have put us through at least as much hell, if not more, than our condition.

themadlolscientist: i appreciate your thoughts because i am in the same position, except i cannot afford medical care, so i don't talk to a shrink at all, but i wouldn't do so even if i had medical insurance (can you say, "waste of time?" i knew you could!). but this report that i am writing about here specifically focuses on how members of "the public" deal with a public trauma, like 911 and the VT shootings, not how we deal with our private (but still very real) traumas, like trying to live with bipolar disorder.

although i agree with what you are saying (while recognizing that talking about it can be very helpful for some people because that's the way they cope and work through things), this report does not specifically address the situation you are referring to.

i know i would be curious to know what sorts of "mental illnesses" or other traumas that "talk therapy" are likeliest to contribute to a positive outcome for, and which "personality types" are most likely to respond to talk therapy. does anyone out there know if studies like this have been done? (i suspect so, but i am not intimately involved with that literature, so i am unaware of such research).